Junction of Fraser River and McLennan River

52.9667 N 119.4292 W — Map 83D/14 — Google — GeoHack

Earliest known reference to this name is 1825 (McMillan)

Name officially adopted in 1989

Official in BC – Canada

John Arrowsmith’s map BC 1859

Milton and Cheadle’s map 1865

Trutch’s map of BC 1871

George Monro Grant’s map of Yellowhead Pass 1872

McEvoy’s map Yellowhead Pass 1900

Collie’s map Yellowhead Pass 1912

Pre-emptor’s map Tête Jaune 3H 1919

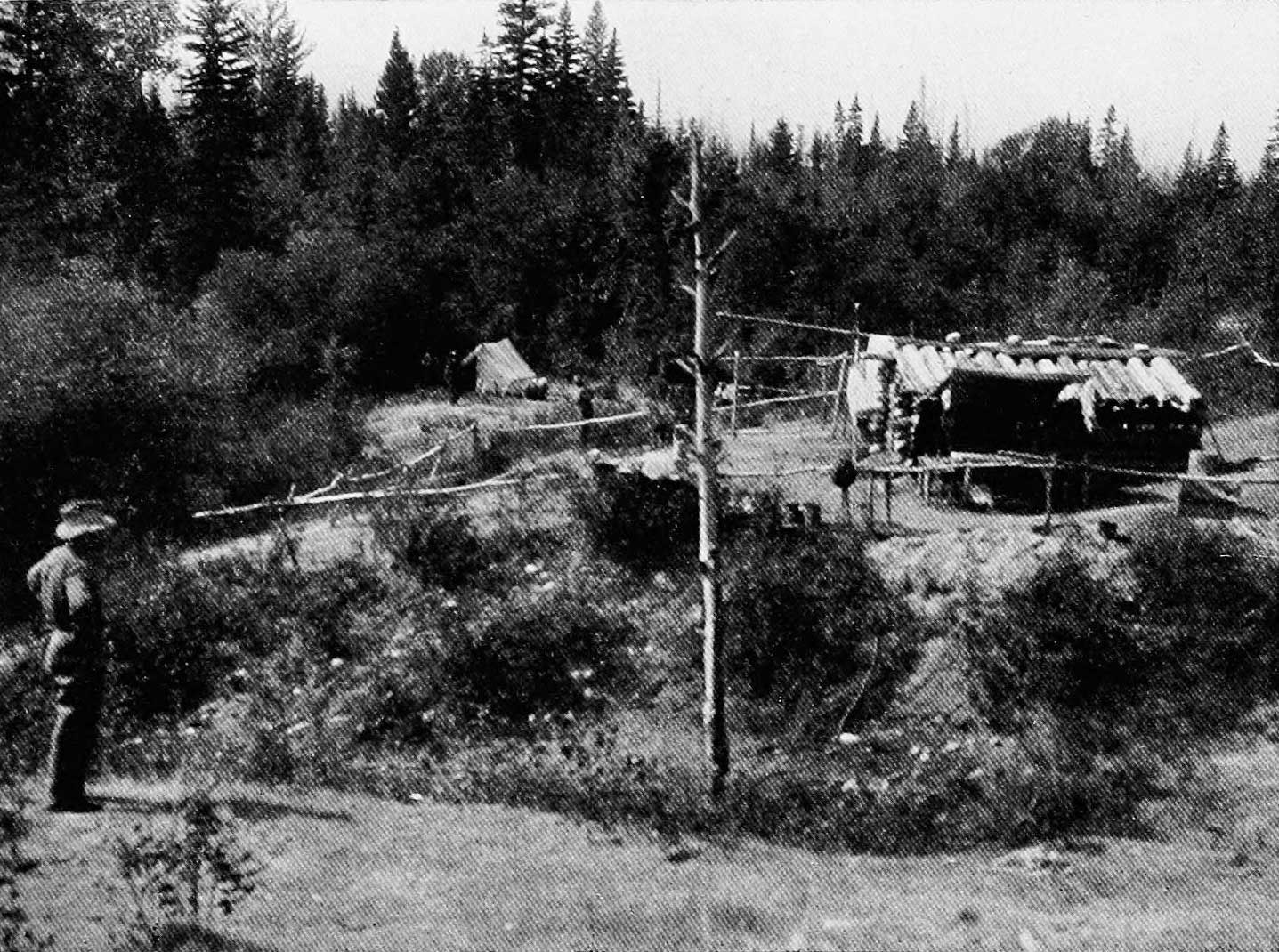

The city of Tête Jaune Cache, 1908

Mary Schäffer Old Indian Trails

Tête Jaune Cache. Mary Schäffer, 1908

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

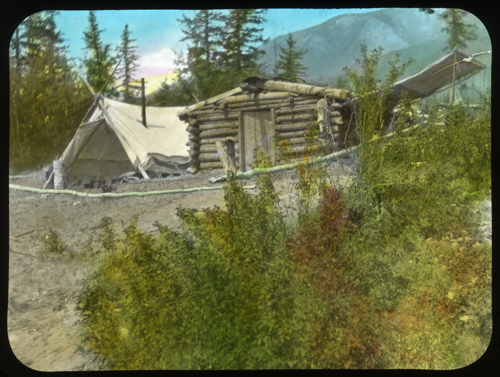

Tête Jaune Cache, showing old camping ground of fur trappers. In the distance is Mica Mountain. 1910

F.A. Talbot, New Garden of Canada

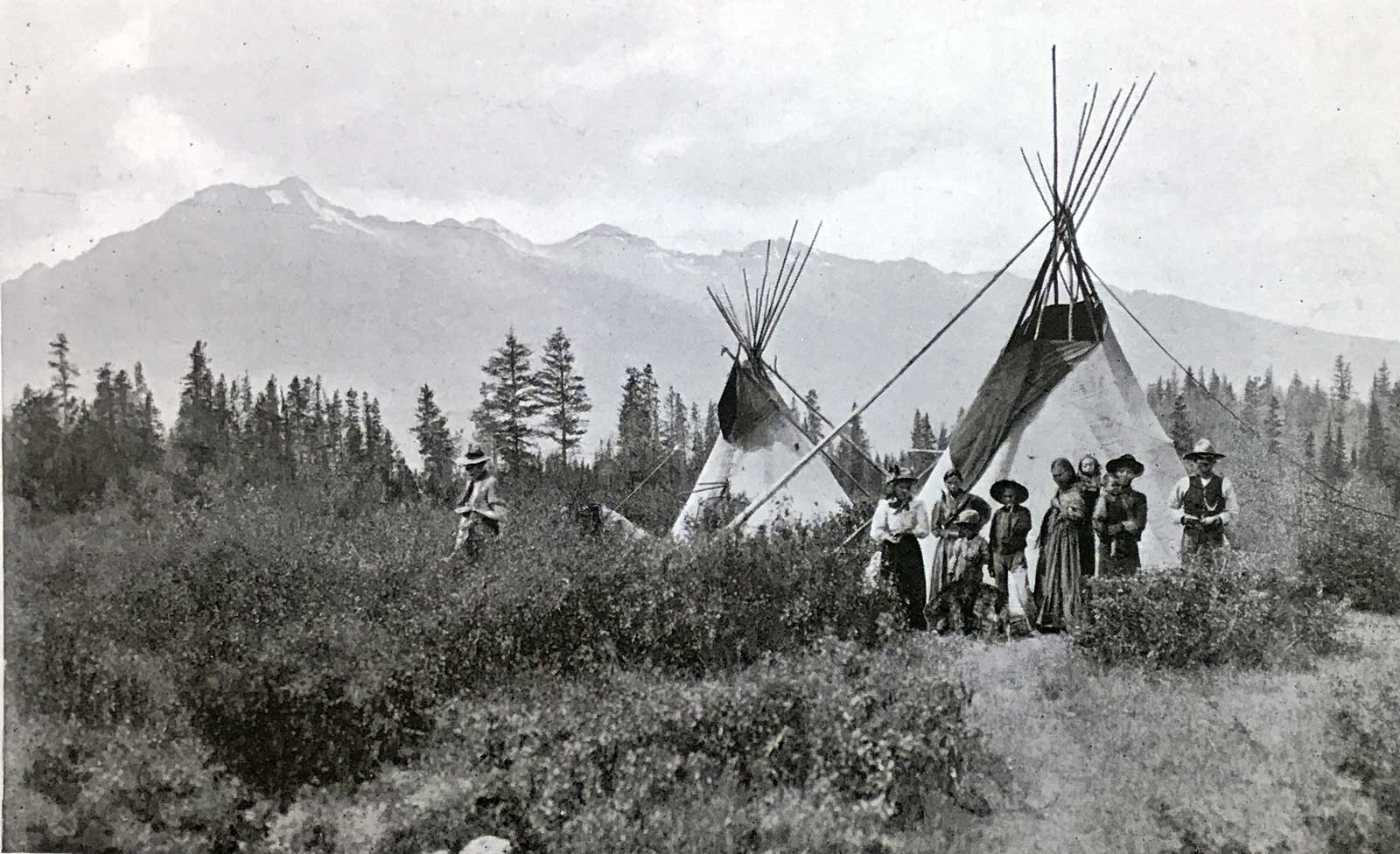

Natives at Tête Jaune Cache. A group of Shuswap Indians. 1910.

F.A. Talbot, New Garden of Canada, 1911

“Tête Jaune” (“Yellow Head”) was the nickname of Pierre Bostonais [d. 1827], of Iroquois descent, who worked for the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company. “Cache” is French for a hiding place. During the fur trade, a cache was built by removing a round piece of turf about eighteen inches across, excavating the dirt, and lining the excavation with dry branches. After the cached goods were inserted, some earth and the round piece of turf were put on top, and the surplus earth all carefully removed.

According to Milton and Cheadle, who passed through the Yellowhead Pass in 1863, Bostonais’s original cache was at the confluence of the Robson River and Fraser River. The present location of Tête Jaune Cache is near the site selected during the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, at the head of navigation on the Fraser River.

“Bostonais” was a name applied by indigenous people to Americans of European descent, “Boston Men.” Normally a nickname, Pierre Bostonais may have acquired it as a family name after his family moved from American territory to the Montreal area. (As early as 1670, a number of Iroquois, converted by French priests, left what is now New York State to live near Montreal.) Iroquois were brought out west by the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as voyageurs, hunters, guides, and trappers. Many Iroquois stayed in the west when their contracts with the fur companies expired, settling east of the Rockies between the Athabasca and Peace Rivers.

Pierre Bostonais first appears in the archives of the Hudson’s Bay Company in January 1805, when the factor at the fur trading post of St. Croix (now in Minnesota) wrote, “This afternoon Tête Jaune’s son expired after a long and painful malady of upwards of three months.” In 1810 Tête Jaune was for a time employed by the North West Company, perhaps arriving at Rocky Mountain House, on the North Saskatchewan River. By 1816, when he is mentioned in the North West Company ledger, Tête Jaune was a “free” Iroquois, not engaged to any fur trade company. Twice in Hudson’s Bay Company books from 1821 to 1823 there are entries of “Pierre Bostonais dit Tête Jaune.”

Colin Robertson, in charge of Fort St. Mary (near the present-day town of Peace River, British Columbia), recorded in his journal for December 1819, “Tête Jaune, the free Iroquois, has given me a chart of that country across the Rocky Mountains.” Tête Jaune guided a party across the mountains the next spring and returned at the end of October. “Tête Jaune and Brother Baptiste arrived — the Iroquois all enjoyed themselves with a booze.” Tête Jaune and Baptiste appear again in 1825, when the Hudson’s Bay Company required a guide over the Yellowhead Pass, then a little-known route. (There is no record that this pass was used by either company prior to 1824, when chief trader Joseph Felix LaRocque tried to establish a post at “Moose or Cranberry Lake.”)

In 1825, Hudson’s Bay Company governor George Simpson [1792–1860] ordered chief trader James McMillan to explore the pass. At Jasper House, McMillan hired Tête Jaune as guide. They left Jasper House on October 18, and by October 24, after a trip of about 120 miles, reached Tête Jaune’s cache. In his report to William Connolly, McMillan specifically mentioned “Tête Jaune’s Cache,” the first recorded reference to this place name.

Tête Jaune probably spent the winter of 1825-26 at Fort Alexandria, on the Fraser River north of Quesnel. In early May 1826, just before the departure of the fur brigade from Fort St. James for Fort Vancouver, Connolly received word about the “Iroquois guide who remains sick at Alexandria.”

In early November 1826, Tête Jaune and Baptiste arrived at Fort St. James. “In the evening that old rogue Tête Jaune, and his brother, arrived from below, dread of the Carriers who threaten vengeance for the death of their relatives, is the cause of their coming this way. These people brought nearly one Pack of Beaver between them.”

Tête Jaune and Baptiste apparently spent the winter of 1826–27 with the indigenous Carriers. The brothers returned to Fort St. James in mid-April. Connolly wrote, “I never saw two more wretched beings in my life — since the Fall they have not Killed one Marten between them. They are however good Beaver Trappers & being well furnished with Traps they may perhaps do well — But they are such notorious rascals that no dependence whatever Can be placed in them.” That fall, the brothers were at Bear Lake (Fort Connelly). “I am glad this district is rid of them,” wrote Connolly. “They are brothers who seldom do any good. And very frequently do Mischief.”

In the spring of 1828 word reached Connolly that Tête Jaune, Baptiste, and their families had been “cut off by the Beaver Indians, as a punishment for Hunting upon their lands.” Connolly wrote that “this Melancholy Occurrence took place last fall at Finlays Branch, but by whom perpetrated could not be ascertained — The natives throughout the District have for a long While past looked upon the Iroquois as Robbers and despoilers of their lands, and it is only in Consideration for us that they have not long before this taken the only means in their power to rid themselves of their depredators.”

Tom Longstaff climbed Mount Assiniboine in 1910, and in This My Voyage relates that “on our return to Banff we were disappointed to find that my old companion Mumm had left the day before with Norman Collie, bound for Mount Robson, by way of Tête Jaune Cache on the Yellowhead Pass. Here a corpse had once been found sitting beside the ashes of a fire: nearby was a cache of food: on the ground beside the body lay a head with yellow locks still adhering to the scalp. From this unsolved tragedy the French speaking half-breeds and later English speaking trappers named the place.” Longstaff noted: “This was the current tradition at the time. But according to Milton and Cheadle it was called after a well-known Iroquois trapper, of the sobriquet Tête Jaune, who used to cache his furs near there. They say that the headless Indian was found far west of the pass.”

Mary Townsend Schäffer visited the area in 1908:

Though Mount Robson had been so long our Mecca, now that we were within reach of Tête Jaune Cache, it seemed a pity not to see that historic point. Who Tête Jaune really was, is a myth. A fair-haired Indian, he is supposed to have had his cache of furs somewhere on the Fraser River. Milton and Cheadle say the true cache was at the Grand Fork. But being a matter of a hundred years ago, and the history of that country being largely handed down by word of mouth, few of the real facts are obtainable. All our knowledge of the present cache in the summer of 1908 was, that it was the meeting-point for the surveyors of the Grand Trunk Pacific and prospectors, that an Indian village was on the far side of the river, and that Swift had told us that “his friend Mr. Reading lived there.…

Then “M.” and I … looked down from a hill on the city of Tête Jaune Cache as she was in 1908. What we saw was a tiny log shack and a tent pitched beside it, both enclosed by a fence, with a few spurious efforts to grow a little garden stuff just inside the fence; a little beyond was another tent. Near the shack stood a terrible looking man clad in rough khaki, his hands in his pockets and his eyes glued on the strangers with a stony stare; by the fence lounged our travelling companions of the day before, who had arrived before us, and out from the far tent strolled two more nomads with unkempt hair, grizzled faces, ragged clothes and moccasins. In that quiet village, they had heard our outfit coming and the population had turned out to see who it was. Strange to say, those who got in ahead of us had never thought to mention there were women coming behind, so that the apparent hostility which froze the blood of the two scared ones, was a ease of pure astonishment, and everyone, for an instant, stood dumb in his tracks.

I speak for no one’s sentiments but my own; but for the time being it seemed to me my hour had come. They looked awful, and stood so terribly still as we slowly filed by them into the open. (It was only later that wondered how much charity and faith might have been mustered on the spur of the moment to welcome us, and realised that we were probably quite as rough-looking in our travel-worn garments as those we rushed to condemn.) It was only a momentary pause, and was quickly broken by the first terrible party mustering a pleasant smile (unmarred by a razor for weeks), coming to greet us cordially, showing us where our horses could pasture, and offering us his own yard as a place to pitch our tent. There wasn’t a tree in it to shelter us from the eyes of the curious, so Chief politely suggested moving back a little from the residential section to a place which our host sarcastically explained was “where all Indians camped.” This was rather unnecessary information, for rags, bones, goathair and hides stared us in the face, and yet we chose it in preference to the too close association of the city limits.

During its heyday in 1913, Tete Jaune Cache stretched from Mile 49 (Henningville) to Mile 53, at Siems Carey wharf and the Foley, Welsh & Stuart wharf.

The Henningville post office, which opened in 1913, and the Tete Jaune post office, opened in 1914, were changed to Tete Jaune Cache in 1917, and the office there remained open until 1967.

- McMillan, James [1783–1858]. Winnipeg: Hudson’s Bay Company archives. Portion of letter James McMillan to William Connelly HBCA B.188/b/4 fo. 9-10 (1825).

- Milton, William Wentworth Fitzwilliam [1839–1877], and Cheadle, Walter Butler [1835–1910]. The North-West Passage by Land. Being the narrative of an expedition from the Atlantic to the Pacific, undertaken with the view of exploring a route across the continent to British Columbia through British territory, by one of the northern passes in the Rocky Mountains. London: Cassell, Petter and Galpin, 1865. Internet Archive

- Schäffer Warren, Mary T. S. [1861–1939]. Old Indian trails. Incidents of camp and trail life, covering two years’ exploration through the Rocky Mountains of Canada. [1907 and 1908]. New York: Putnam, 1911, p. 339. Internet Archive

- Talbot, Frederick Arthur Ambrose [1880–1924]. The new garden of Canada. By pack-horse and canoe through undeveloped new British Columbia. London: Cassell, 1911. Internet Archive

- Talbot, Frederick Arthur Ambrose [1880–1924]. The making of a great Canadian railway. The story of the search for and discovery of the route, and the construction of the nearly completed Grand Trunk Pacific Railway from the Atlantic to the Pacific with some account of the hardships and stirring adventures of its constructors in unexplored country. London: Seely, 1912. Internet Archive

- Augustine, Alpheus Price [d. 1928]. “Report on Surveys on the South Fork of Fraser River.” Report of the Minister of Lands for the Province of British Columbia for the year ending 31st December 1912, (1913):240-242. Google Books

- McElhanney, William Gordon [1877–1965]. “Report on surveys on the Upper Fraser River below Yellowhead Pass. March 12, 1912.” Report of the Minister of Lands for the Province of British Columbia for the year ending 31st December 1912, (1913). Google Books

- Longstaff, Tom George [1875–1964]. This My Voyage. London: John Murray, 1950

- MacGregor, James Grierson. Pack Saddles to Tête Jaune Cache. Edmonton: Hurtig, 1962 (reprint 1973)

- Gates, Charles Marvin. Five fur traders of the Northwest : being the narrative of Peter Pond and the diaries of John Macdonell, Archibald N. McLeod, Hugh Faries, and Thomas Conner . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1933

- MacDonald, Ervin Austin. The Rainbow Chasers. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1982

- Topping, William. A checklist of British Columbia post offices. Vancouver: published by the author, 7430 Angus Drive, 1983

- Smyth, David. “Tête Jaune.” Alberta History, 32, no. 1 (1984)

- Akrigg, Helen B., and Akrigg, George Philip Vernon [1913–2001]. British Columbia Place Names. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997. Internet Archive

- Klan, Yvonne Mearns. “That old Rogue, the Iroquois Tête Jaune.” British Columbia Historical News, Vol 34 No. 1 (Winter 2000/2001):19–22. University of British Columbia Archives

- Tête Jaune Cache History. 2022 Valemount Museum. Valemount Museum

I’m glad I found this. I’ve been looking for more details about Pierre Bostonais (Tete Jaune) as I’m writing a novel that features the area. So far, your well-researched post has more information on him than anywhere else I’ve looked. It makes him seem more of a character. If you run across any additional information, I’d love to see it.

Ruth

R.E. Donald, author of the Highway Mysteries series

http://redonald.com