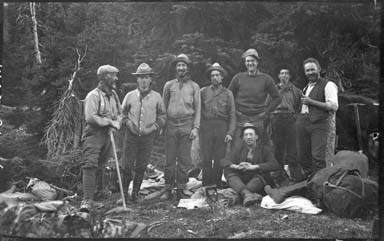

Camp on Calumet Creek, below Moose Pass. James Shand-Harvey, George Kinney, Conrad Kain, Donald “Curly” Phillips, Charles Walcott Jr., Harry H. Blagden, Ned Hollister, J. H. Riley and A. O. Wheeler. Smithsonian-Alpine Club of Canada Robson Expedition (1911 )Photo: Byron Harmon, 1911. Canadian Alpine Journal 1912, p. 34. Original negative: Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

A.O. Wheeler, Donald “Curly” Phillips, Harry Blagden, Ned Hollister, Charles Walcott Jr., James Shand-Harvey, Casey Jones and Rev. George B. Kinney, near Maligne Lake, Smithsonian-ACC Robson Expedition

Photo: Byron Harmon, 1911 Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

July 1 – September 16, 1911

The 1911 Alpine Club of Canada–Smithsonian joint expedition to the Mount Robson region was initiated by Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945], director of the Alpine Club of Canada. In his report Wheeler wrote:

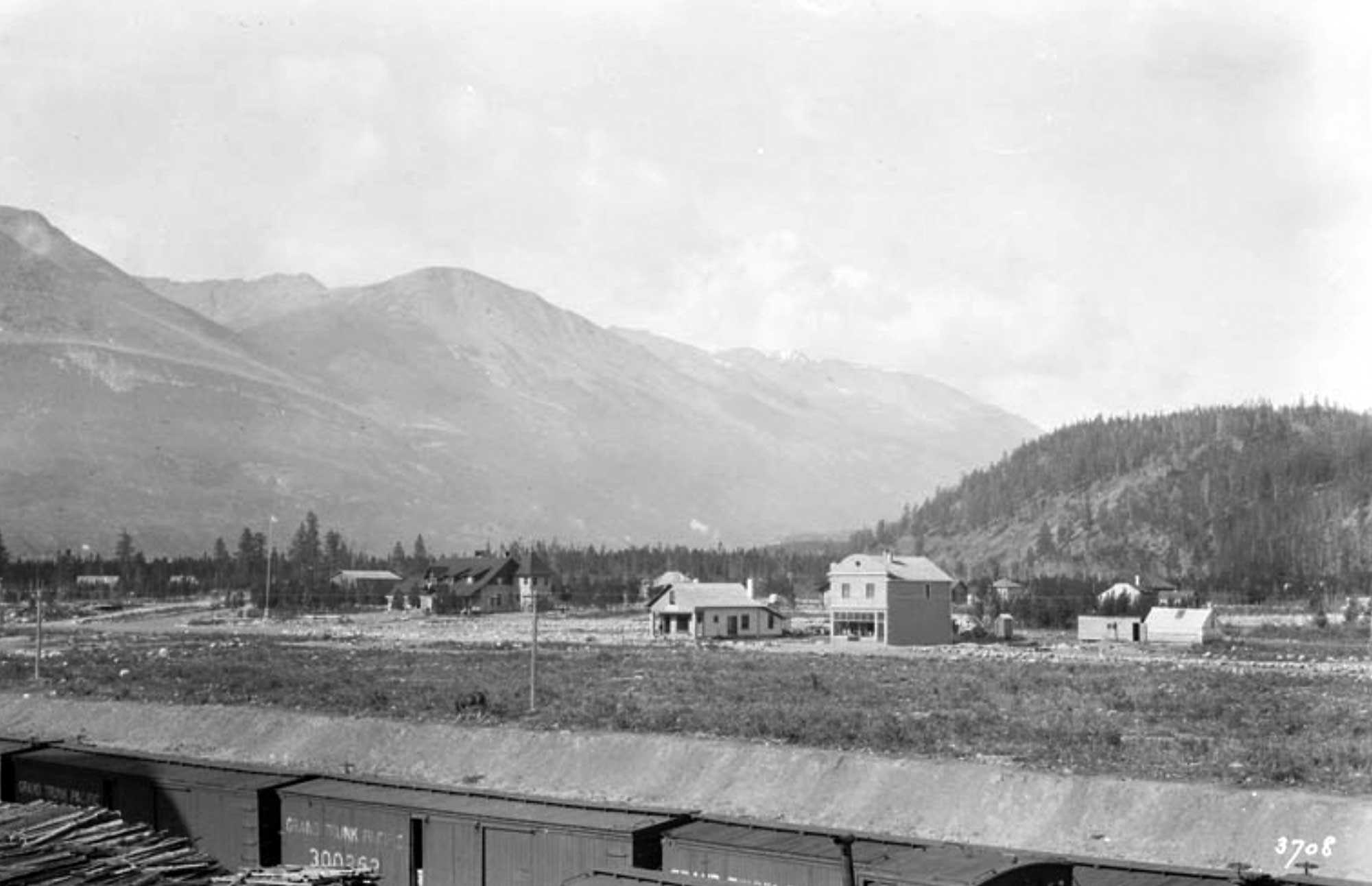

Mount Robson is undoubtedly the highest peak of the region… so when the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway pushed the advancing steel in sight of the main range, it was decided by the Alpine Club of Canada to organize an expedition and make direct investigations on its own behalf and in accordance with the propaganda laid down in its constitution, viz., the encouragement of mountain craft and the opening of new regions as a national playground.

Subsequent co-operation and financial assistance by the British Columbia, Alberta and Dominion Governments made it possible to enlarge the scope of the expedition, and an investigation of the fauna, flora, and geology was added to the topographical work first planned. An attempt was made to interest Canadian scientists in the expedition, but without success, so the matter was submitted to Dr. Charles Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute of Washington, who collaborate most heartily and sent a party of four to join and work with the Alpine Club. [1]

Charles Doolittle Walcott [1850–1927], secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, agree to conduct scientific studies “under the permit of the geology, flora and fauna of the area,” and planned to attend personally, but his wife died in a rail accident shortly before the event. The Smithsonian called its participation the Biological Survey of the Canadian Rockies, recognizing it as an excellent opportunity to gather specimens from the region. The Alpine Club of Canada also helped to pay for a portion of the Smithsonian’s costs for sending staff. Official Smithsonian staff included N. (Ned) Hollister, Assistant Curator in the Division of Mammals (leader); and Joseph Harvey Riley, Aid in the Division of Birds. They were assisted by Charles D. Walcott, Jr. (son of the Secretary of the Institution) and H. H. Blagden. All specimens collected came to the Smithsonian, including mammals, birds, reptiles, batrachians, fishes, invertebrates, and plants. In 1912 Walcott conducted his own investigations in the Mount Robson area.[2]

Wheeler continued:

Mountaineering was not the primary object and the ascent of Robson Peak for the second time had not even received consideration. The intention was to investigate the facilities for holding one of the Club’s big camps close to the great monolith and, while doing so, to make topographical survey of such area as might fall within the scope of the expedition, using photo-topographic methods a as a basis of the work. Notwithstanding, some thirty peaks were climbed, ranging in altitude from 7,000 to 11,000 feet above sea-level.

The expedition was made possible through the co-operation of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, which contributed handsomely towards the expenses. The railway company proposed to open up the northern section of the mountains in a manner similar a to that being done by the Canadian Pacific Railway in the southern section, and was naturally interested in the publicity that would ensue.

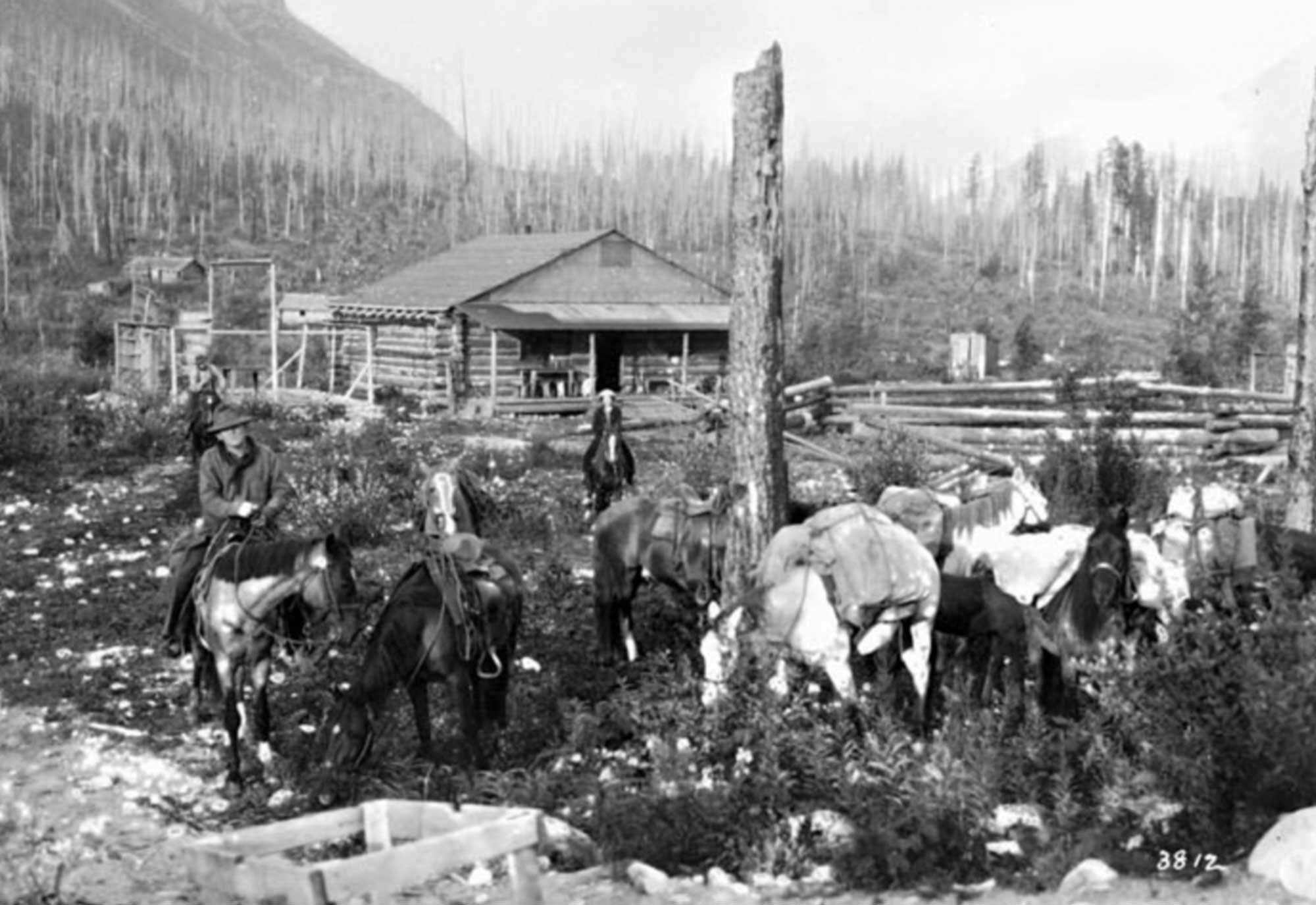

The original party consisted of the writer in charge, Konrad Kain, the Club’s professional guide, Byron Harmon, the Club’s official photographer, a and a cook, with the transport and outfitting in the hands of Donald Phillips. Later, George B. Kinney was added as an assistant. Subsequent co-operation and financial assistance by the British Columbia, Alberta and Dominion Governments made it possible to enlarge the scope of the expedition, and an investigation of the fauna, flora, and geology was added to the topographical work first planned. An attempt was made to interest Canadian scientists in the expedition, but without success, so the matter was submitted to Dr. Charles Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute of Washington, who collaborate most heartily and sent a party of four to join and work with the Alpine Club.

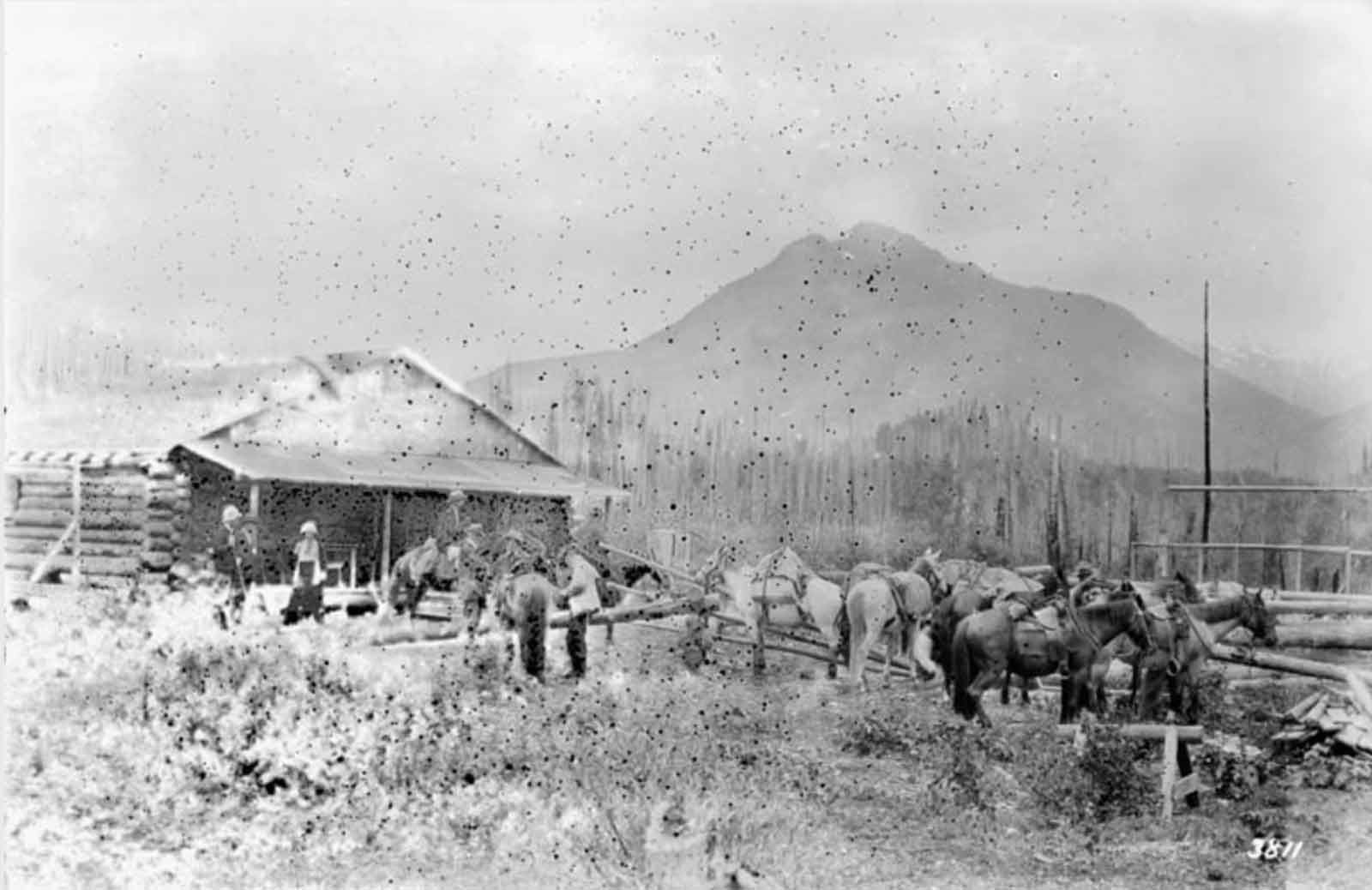

The general line of travel may be described as follows: Commencing at Henry House, the eastern extremity of the survey, the route lay up the valleys of the Athabasca and Miette rivers to the summit of the Continental Divide at the Yellowhead Pass. Thence down the valley of Yellowhead Lake and Fraser River for seventeen miles to the junction of the Moose River with the Fraser. Then up the Moose River Valley to the Moose Pass, where the Continental Divide was again crossed, and down the valley of Calumet Creek (local name Pipestone Creek), to the Smoky River Valley. The Smoky River Valley was next ascended to the Robson Pass where, re-crossing the Continental Divide, the valley of the Grand Fork River was followed to the Fraser Valley, which was ascended to the junction of the Moose River Valley. By this means complete irregular circuit of very nearly 100 miles was made round Mt. Robson, the first that ever has been made, and all the enclosed territory was surveyed as well as a considerable area outside of it.

Nunerous articles about the expedition were published in the Canadian Alpine Journal, Volume 4, 1911. Beginning with Wheeler’s own report, quoted above, accompanied by his topographic map of Mount Robson, there were articles from the Smithsonian party on mammals[3], birds [4], and plants [5], as well as two reports on the return trip to Laggen (Lake Louise) by packhorse.[6, 7]

People involved with the expedition

- Alpine Club of Canada [founded 1906] sponsor

- Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846] sponsor

- Wheeler, Arthur Oliver [1860–1945] ACC leader

- Walcott, Charles Doolittle [1850–1927] Smithsonian sponsor

- Hollister, Ned [1876–1924] Assistant Curator in the Division of Mammals (leader)

- Riley, Joseph Harvey [1873–1941] Aid in the Division of Birds

- Blagden, Henry Harrison [1888–1957] Smithsonian, hunter

- Walcott Jr., Charles Doolittle [1889–1913] Smithsonian, hunter

- Harmon, Byron [1876–1942] photographer

- Kain, Conrad [1883–1934] guide

- Phillips, Donald “Curly” [1884–1938] outfitter

- Shand Harvey, James [1880–1968] assistant

- Kinney, George Rex Boyer [1872–1961] assistant

- Jones, Casey cook

References:

- 1. Wheeler, Arthur Oliver [1860–1945], and Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846]. “The Alpine Club of Canada’s expedition to Jasper Park, Yellowhead Pass and Mount Robson region, 1911.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):9-80. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

- 2. Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846]. Expedition History, 1911 (1911). Smithsonian Institution Archives

- 3. Hollister, Ned [1876–1924], and Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846]. “Mammals of the Alpine Club Expedition to the Mount Robson Region.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 No. 2 (1912):1-46. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

- 4. Riley, Joseph Harvey [1873–1941], and Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846]. “Birds Collected or Observed on the Expedition of the Alpine Club of Canada to Jasper Park, Yellowhead Pass and Mount Robson Region.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 No. 2 (1912):47-75. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

- 5. Standley, Paul C., and Smithsonian Institution [founded 1846]. “Plants of the Alpine Club Expedition to the Mount Robson Region.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 No. 2 (1912):76-. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

- 6. Kinney, George Rex Boyer [1872–1961]. “Trail From Maligne Lake To Laggan. Report of the Rev. G. Kinney to the Alpine Club of Canada.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):81. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

- 7. Phillips, Donald “Curly” [1884–1938]. “Fitzhugh to Laggan. Report by Donald Phillips to A. O. Wheeler, Director of the Alpine Club, Canada.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):83-86. Alpine Club of Canada [accessed 2 April 2025]

![Press Excursion Party at Summit [Yellowhead Pass] Photo: William James Topley, 1914](/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/topley-excursion-party.jpg)