Forks N off Highway 16 NW of McBride

53.2625 N 120.2898 W Google — GeoHack

Roads are not in the official geographical names databases

Follows Doré River.

Follows Doré River.

Ray Zillmer

Wikipedia

Raymond T. Zillmer [1887–1960]

b. 1887 — Milwaukee, Wisconsin

d. 1960 — Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Zillmer was an American attorney, mountaineer, and conservationist. During the 1930s-40s, Zillmer became an accomplished and respected explorer and mountaineer. In July, 1934 Zillmer was part of a team of five mountaineers who completed the first ascent of Anchorite Peak, British Columbia, Canada. He would go on to complete several other first ascents and describe previously uncharted lands. In the summer of 1938, he and Lorin Tiefenthaler retraced the steps of the expedition of Alexander Mackenzie [1764–1820] in 1792-93 between the Fraser and Bella Coola rivers. He described the adventure in detail in his first of four articles published in the Canadian Alpine Journal.

Named in 1925 after Hon. Peter Talbot (1854-1919), Lacombe; member of the Senate of Canada, 1906-1919.

Colour-coded map depicting surveyed lands respectively open and closed to preemption. Depicts land recording divisions, game reserves, communities, bodies of water, and transport routes.

Adolphus Moberly, an Iroquois halfbreed. Coleman 1908 p. 360. [1]

b. 1887 — Jasper, Alberta ?

Adolphus Moberly, a Métis, was guide for Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939] on the geology professor’s 1908 attempt to climb Mount Robson. “Adolphus was the most typical and efficient savage I ever encountered,” Coleman wrote, “a striking figure, of powerful physique and tireless muscles, and thoroughly master of everything necessary for the hunter in the mountains. Mounted erect on his horse, with gay clothing and trappings, he was the ideal centaur.” [2] Moberly led Coleman’s party up the Moose River valley, and left the group after pointing out the way to Robson Pass. Coleman named Adolphus Lake after Moberly.

Adolphus Moberly was son of Ewan Moberly and grandson of the Iroquois Suzanne Cardinal (or Kwarakwante) and Hudson’s Bay Company clerk Henry John Moberly [1835–1931], who served at Jasper House from 1858 to 1861.[3]

Henry Moberly’s Métis offspring John, Ewan, and grandsons Adolphus and William (Bill) were four of the seven families that were affected by the creation of the “Jasper Forest Park.” An Order in Council was passed in September 1907 by the Canadian Federal Government to create this national park.[4] An initial payment was made to the squatters in February, 1910, when the agreement was finalized, although the final payments were not made until some time later. An Order in Council of April 151 1910, lists the following compensatory payments which were made: Ewan Moberly $1670, William Moberly $ 175, Adolphus Moberly $ 180, John Moberly $1000, Isadore Findlay $ 800, Adam Joachim $1200. [5]

James Shand Harvey [1880–1968], who spent decades as a guide and packer in the area around Jasper, Yellowhead Pass and Tête Jaune Cache, was interviewed in 1967: “On my side of the river (Athabasca) was Ewan Moberly, Adam Joachim, and Dolphus, Ewan’s son. Adolphus built on the west side of Snaring. He had a little shack in there on the right hand side as you go to Swift’s. That was Dolphus.”[6] The Snaring River enters the Athabasca about 20km north of Jasper.

Adolphus’s family was among the six or seven Métis families who were forced to leave the Jasper area after the establishment of Jasper Forest Park in 1907. “The fall of 1909 there was Adam Joachim, Tommy Groat, William, Adolphus, if I remember rightly where were four men came from Jasper House,” recalled James Shand Harvey [1880–1968]. “William and Adolphus Moberly, and there was Tommy Groat, he was just going to get married, no, he was married then, to his wife Clarice (Clarice Moberly, Ewan’s daughter), and Adam Joachim. Old Ewan and John, they both stayed on the place, figured they were too old to work, the younger fellows could build the houses. They put the houses up and some time before New Year they moved in. They stayed there at Rat Lake. And the only one of the bunch that did not go to Grande Cache was Isadore Finley.” [7]

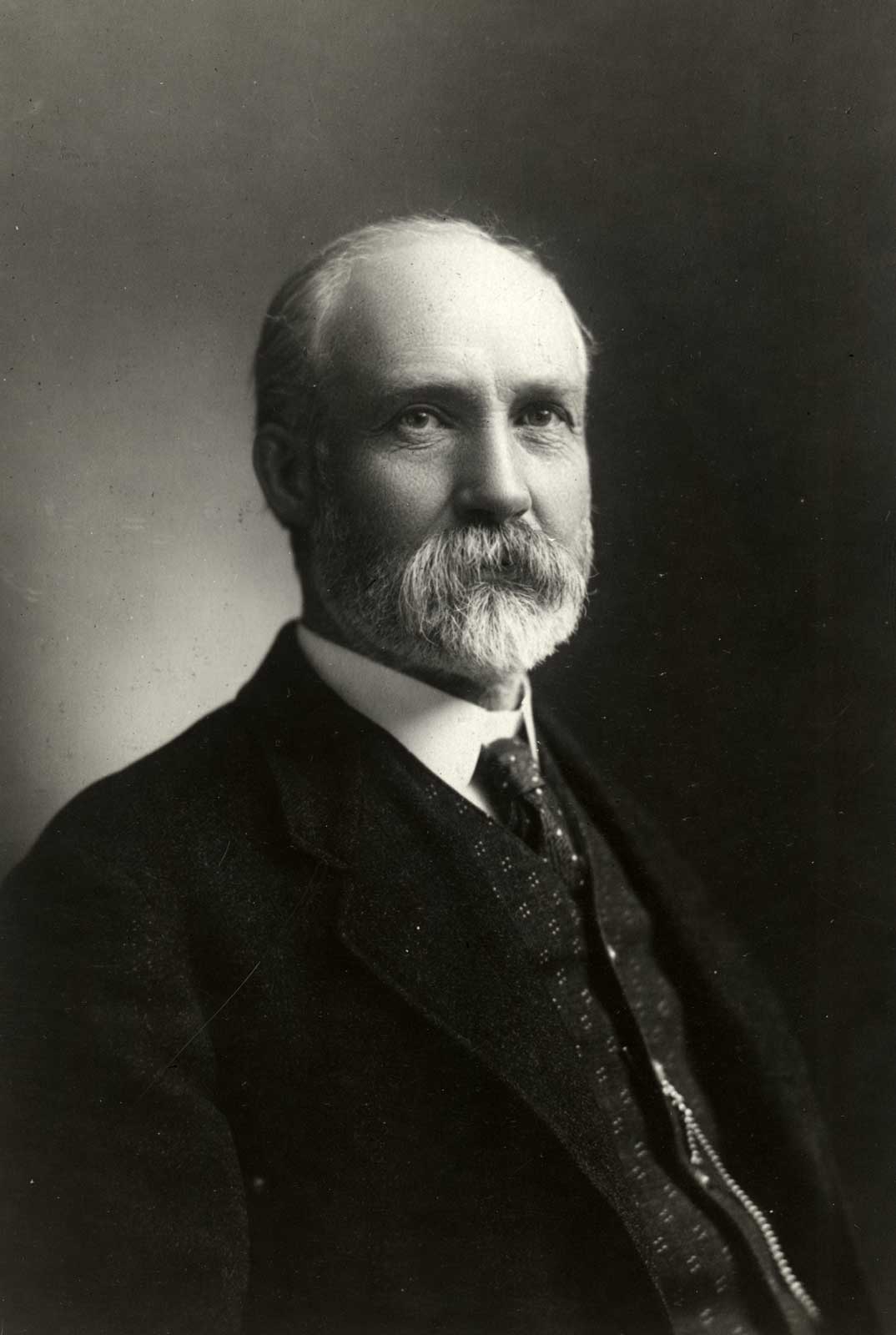

Arthur P. Coleman University of Toronto Archives

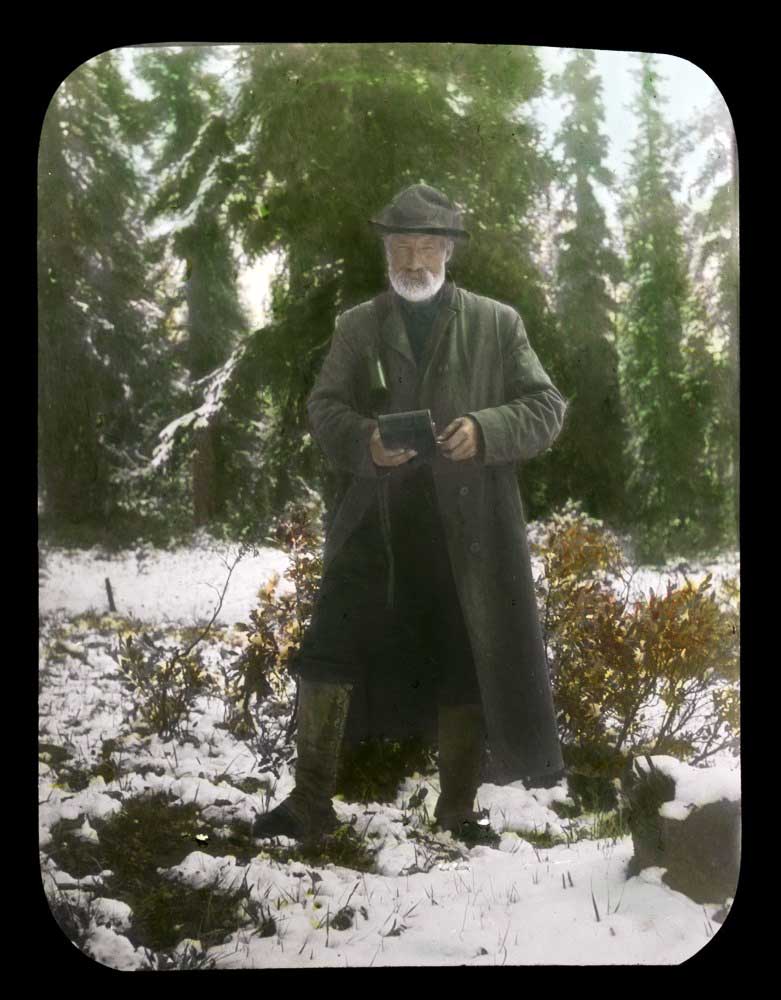

Dr. A. P. Coleman. Lantern slide by Mary T. S. Schäffer Warren, 1907 Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Moore family fonds

b. 1852 — Lachute, Quebec

d. 1939 — Toronto, Ontario

Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939], a professor of geology at the University of Toronto, was the first person of European descent to record an attempt to climb Mount Robson. In 1907, accompanied by his brother Lucius and George R. B. Kinney [1872–1961], he approached via the valley of the Robson River and climbed above Kinney Lake. The pack trip from Laggan (Lake Louise) consumed most of their resources, and snow in early September drove them away.

Coleman’s party returned in 1908, guided by John Yates [1880–?] and Adolphus Moberly [1887–?], who took them up the Moose River valley. The party spent 21 days in the area, but only twice were there two successive days of good weather. On one climb they reached almost 11,000 feet (3350 m), but were turned back by darkness.

Born at Lachute, Canada East, Coleman studied at universities in Ontario and Germany. He was a fellow the the Royal Geographical Society and second president of the Alpine Club of Canada. He started his explorations in the Rocky Mountains in 1884. The first climber to pay serious attention to peaks in the vicinity of Athabasca Pass, in 1892 and 1893 Coleman led parties hoping to climb the famous mountains Brown and Hooker, which botanist David Douglas [1799–1834] had described in 1828 as being over 16,000 feet (4880 m) high. Coleman discovered their heights were less than 10,000 feet (3050 m).

Coleman named the following places in the Mount Robson region: Adolphus Lake, Berg Lake, and Kinney Lake.

He was author of The Canadian Rockies (1911) and Ice ages, recent and modern (1926), and was joint author of Elementary Geology (1922). He died, unmarried, in Toronto.

Smithsonian Institution

Founded 1846

The Alpine Club of Canada also helped to pay for a portion of the Smithsonian’s costs for sending staff. Official Smithsonian staff included leader Ned Hollister [1876–1924], assistant curator in the division of mammals, and Joseph Harvey Riley [1873–1941], aid in the division of birds. They were assisted by Charles Doolittle Walcott Jr. [1889–1913], (son of the secretary of the Institution), and Henry Harrison Blagden [1888–1957]. All specimens collected went to the Smithsonian, including mammals, birds, reptiles, batrachians, fishes, invertebrates, and plants.

In 1912 secretary Charles Doolittle Walcott [1850–1927] led a geological expedition to the same region.

The boundary between the Provinces of Alberta and British Columbia is defined by Sections 7 and 8 of the Imperial Act 29 and 30 Victoria, Chapter 67, (1858) which are as follows:-

7. Until the Union, British Columbia shall comprise all such territories, within the Dominion of Her Majesty, as are bounded to the south by the territories of the United States of America, to the west by the Pacific Ocean and the frontier of the Russian territories in North America, to the north by the Sixtieth Parallel of North Latitude, and to the East from the Boundary of the United States Northwards by the Rocky Mountains and the One hundred and twentieth Meridian of West Longitude; and shall include Queen Charlotte’s Island and all other Islands adjacent to the said Territories, except Vancouver Island and the Islands adjacent thereto.

*8. After the Union, British Columbia shall comprise all the Territories and Islands aforesaid and Vancouver Island and the Islands adjacent thereto.”

In the report of the Minister of the Interior to His Royal Highness in Council, which was approved on the 18th day of February, 1913, is embodied the following interpretation of the above definition, which interpretation was drawn by the Surveyor General of Dominion Lands and concurred in by the several Governments concerned:

“Between the International Boundary and the 120th degree of longitude, the Interprovincial Boundary is the line dividing the waters flowing into the Pacific Ocean from those flowing elsewhere. This line may cross several times the meridian of 120° longitude. Should this be the case, it is proposed that the Interprovincial Boundary follow the watershed line from the International Boundary to the most northerly crossing of the meridian and thence follow the meridian to the 60th degree of latitude. The watershed line being natural feature is preferable to the meridian as a boundary and there are as many chances that the proposal, if agreed to, shall be in favour of one Province as of the other.”

From the above quoted sections of the Imperial Act and the interpretation thereof adopted by the several Governments concerned, it will be seen that the Interprovincial Boundary, from the International Boundary to the most northerly crossing of the 120th meridian of west longitude, exists as a natural topographical feature, namely: the crest or watershed of the Rocky Mountains. Its precise delimitation, therefore, was not a matter of urgent necessity for many years after the Act was passed, but various causes arose, and grew in importance year by year, which made such delimitation advisable and even necessary.

Chief among these may be cited the discovery of valuable coal deposits at widely separated points of the Boundary, and extending over very large areas on either side of it. As a result of these discoveries, leases of coal lands have been issued by the Crown, either in the right of the Dominion of Canada or in that of the Province of British Columbia. In some cases the descriptions of these leases were based on surveys made by Dominion or Provincial land surveyors, who, for that purpose, were obliged to assume a provisional boundary; since the Boundary, or watershed, is by no means so well defined on the ground as might be supposed, particularly in the wider passes, the provisional boundary thus assumed is rarely, if ever, correct, and surveys made by Dominion and Provincial land surveyors, respectively, have been found to overlap.