Flows N into Whirlpool River

52.5731 N 118.0589 W — Map 083D09 — Google — GeoHack

Name officially adopted in 1947

Official in Canada

Boundary Commission Sheet 26 (surveyed in 1920)

Named in association with Divergence Peak.

Named in association with Divergence Peak.

Captain Charles Fryatt, ca. 1915

Wikipedia

Named in 1921 after Charles Algernon Fryatt [1872 –1916], a British merchant seaman who was court martialled by the Imperial German Navy for attempting to ram a German U-boat in 1915. When his ship, the SS Brussels, was captured off occupied Belgium in 1916, Captain Fryatt was court-martialled under German military law and sentenced to death for “illegal civilian warfare.” International outrage followed his execution by firing squad near Bruges, Belgium. In 1919, his body was reburied with full honours in the United Kingdom.

The name was conferred by surveyor Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945] of the Alberta-British Columbia Boundary Commission, who worked the area in 1920:

The south branch [of the Whirlpool River] is the main stream. …. Near the upper end it turns and leads to a large glacier, being divided into two parts by a thickly forested elevation rising between them. The glacier which has undoubtedly originated the gravel flat, is the surplus discharge of a broad icefield at the northeastern corner of which stands Mt. Scott, and Mt. Hooker at the southwestern. The name “Scott” was given to a mountain and to the glacier by A. L. Mumm, Vice-President of the Alpine Club (England), after the celebrated explorer who lost his life in his famous expedition to discover the South Pole. In 1913 Mumm and Geoffrey Howard visited Athabasca Pass in an endeavour to elucidate the mystery of Mts. Brown and Hooker. It appears, however, that the name Mt. Scott was conferred upon the mountain that was named Hooker by David Douglas and, in consequence, the name has been transferred to the high mountain at the northeastern corner of the icefield. These gentlemen also appear to have conferred the name Mt. Patricia upon the massif here referred to as Mt. Fryatt. The latter is thought to be more appropriate in conjunction with Mt. Edith Cavell, directly opposite on the other side of the valley of the Whirlpool.

Richard William Cautley

Photo from “Compass to Satellite” by W.D. Stretton p. 42 (Canadian Surveyor vol 31 no 4) Alberta’s Land Surveying History

Richard William Cautley, D.L.S., A.L.S., C.E.

b. 5 September 1873 — Petworth, Sussex, England

d. 13 September 1953 — Victoria, B.C.

The Alberta boundary commissioner was responsible for surveying the boundary in the passes. Cautley was an experienced surveyor, having obtained his first commission in 1896. Although Cautley was responsible for the surveys in the passes, the location of the monument positions was decided collectively by the Commission, which included as British Columbia commissioner Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945].

Cautley andWheeler wrote the reports for the Commission and supervised production of the maps After 1924 Cautley went to Ottawa with the Department of the Interior and was responsible for the survey of many of the national park sites in the maritime provinces.

He came to Canada at the age of 17 and became attached to a firm of surveyors in British Columbia. Later, he went north into the Klondike at the time of the gold rush and was engaged in the recording and inspection of mineral claim surveys. Upon termination of the gold rush, his footsteps led to Edmonton where he formed the land surveying firm of Cautley and Cote. Later, he went into partnership with his brother Reginald Hutton Cautley. Cautley was a charter member of the Alberta Land Surveyors’ Association, and was the Association’s president in 1914.

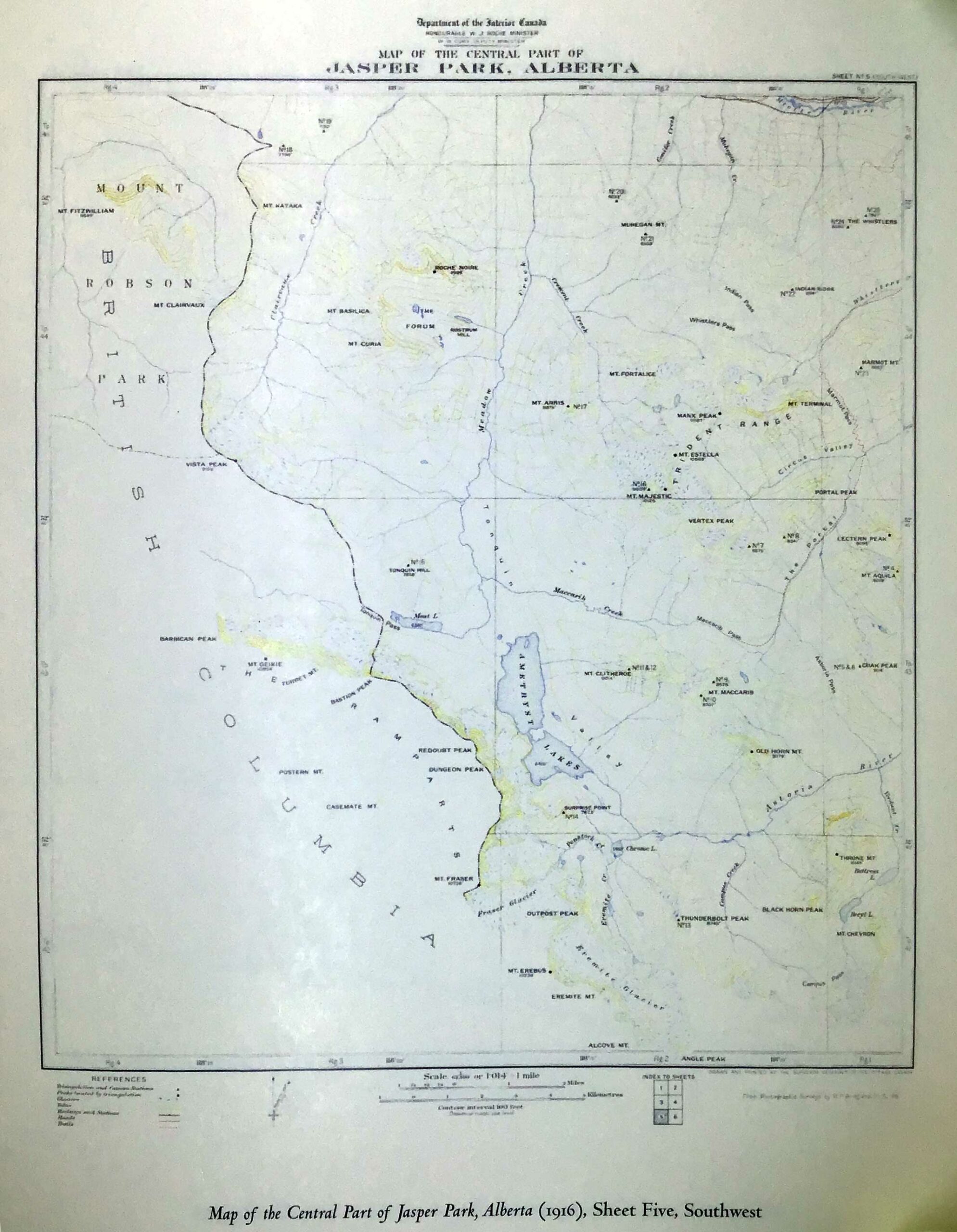

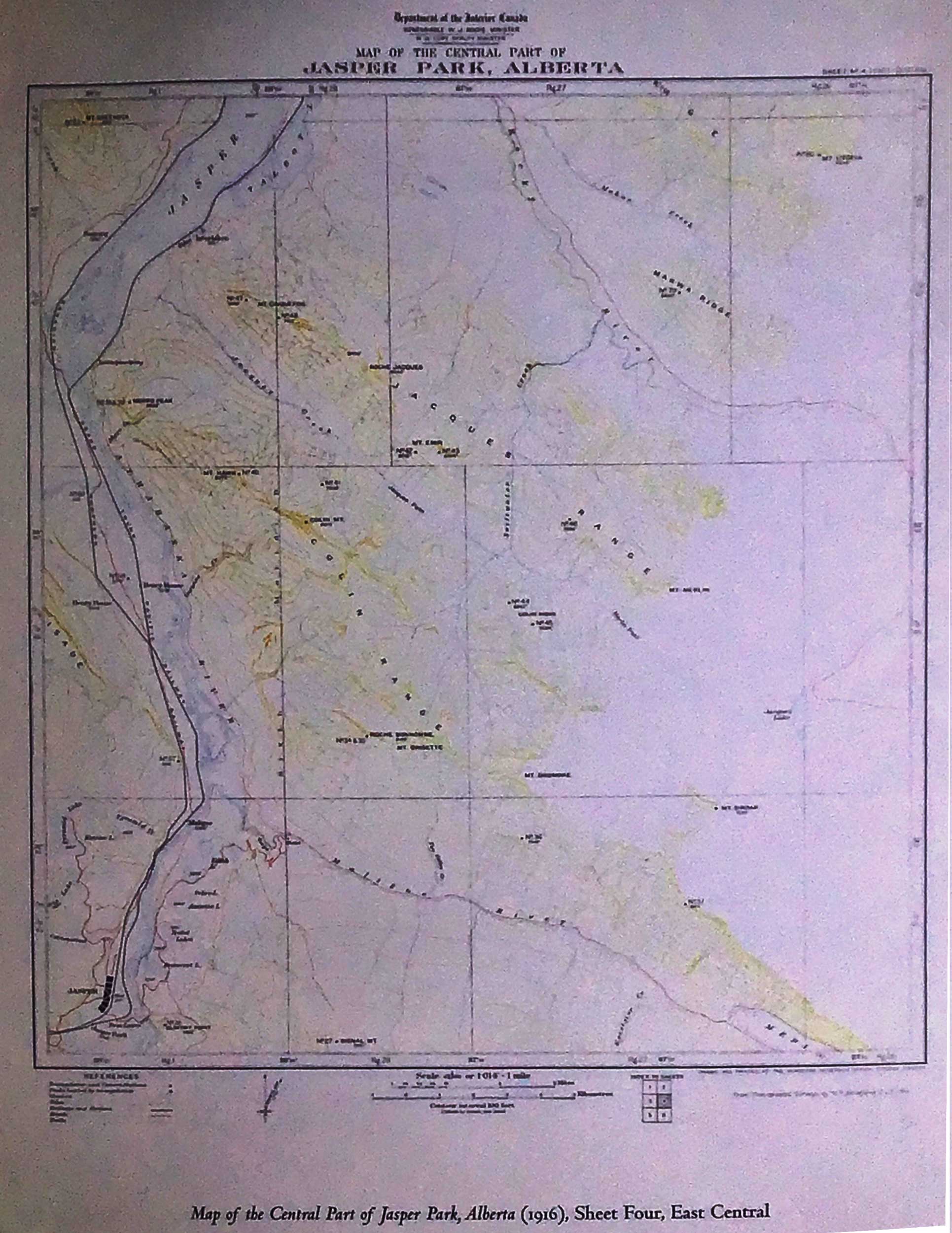

Map of Central Part of Jasper Park, Alberta

Department of the Interior Canada

Sheet Four, East Central

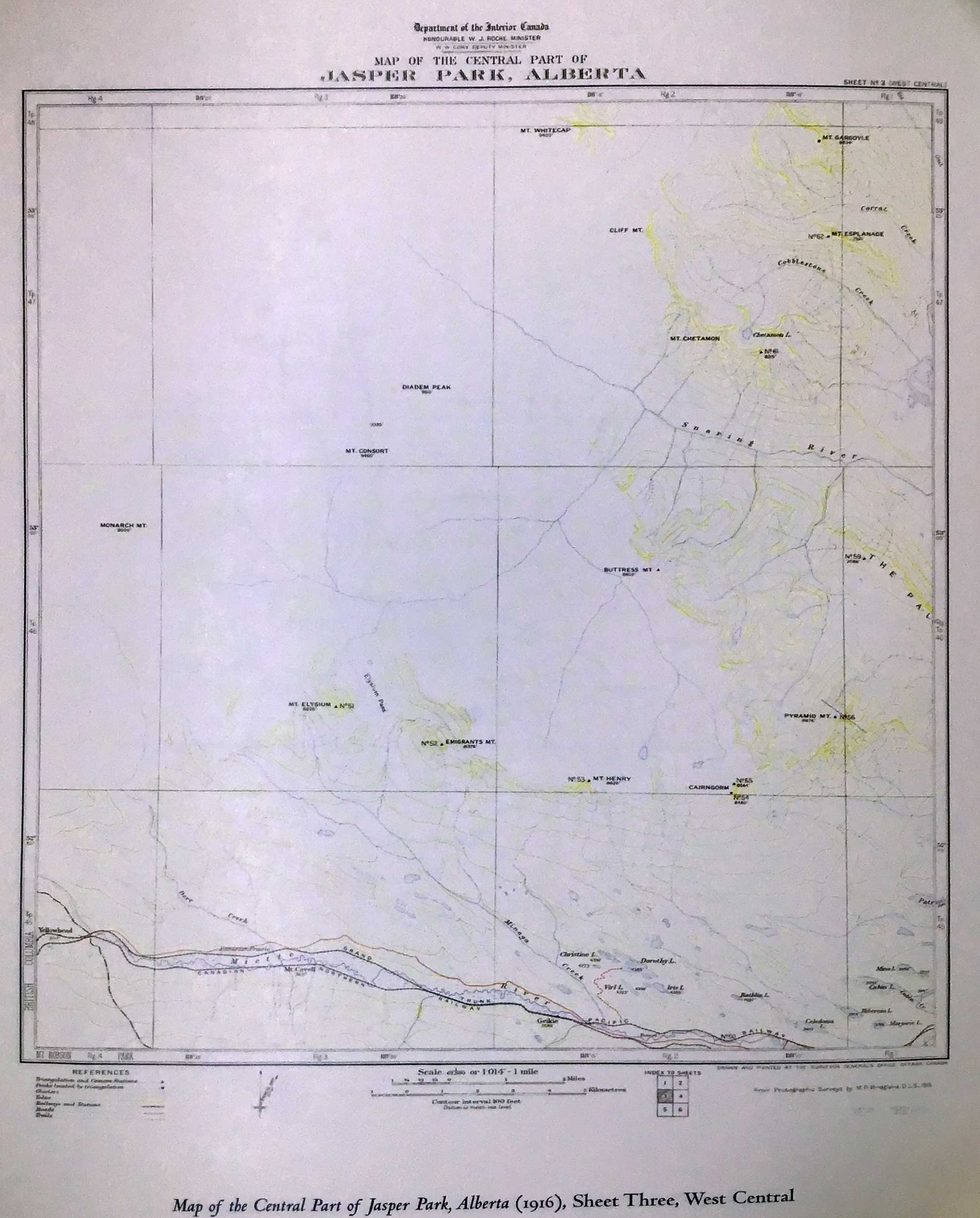

Map of Central Part of Jasper Park, Alberta

Department of the Interior Canada

Sheet Three, West Central

Morrison Parsons Bridgland

b. 1878 — Toronto, Ontario, Canada

d. 15 January 1948 — Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Bridgland gave practically his whole active field of service to this class of surveying and became recognized as a world authority in photographic surveying. He was the author of several papers dealing with optics and the mathematical solution of problems pertaining to the application of photographic information translated at scale to the flat map.

Bridgland lived in Calgary until his retirement in 1935. He was survived by his wife, Mary, and two sons, Charles and Edgar.