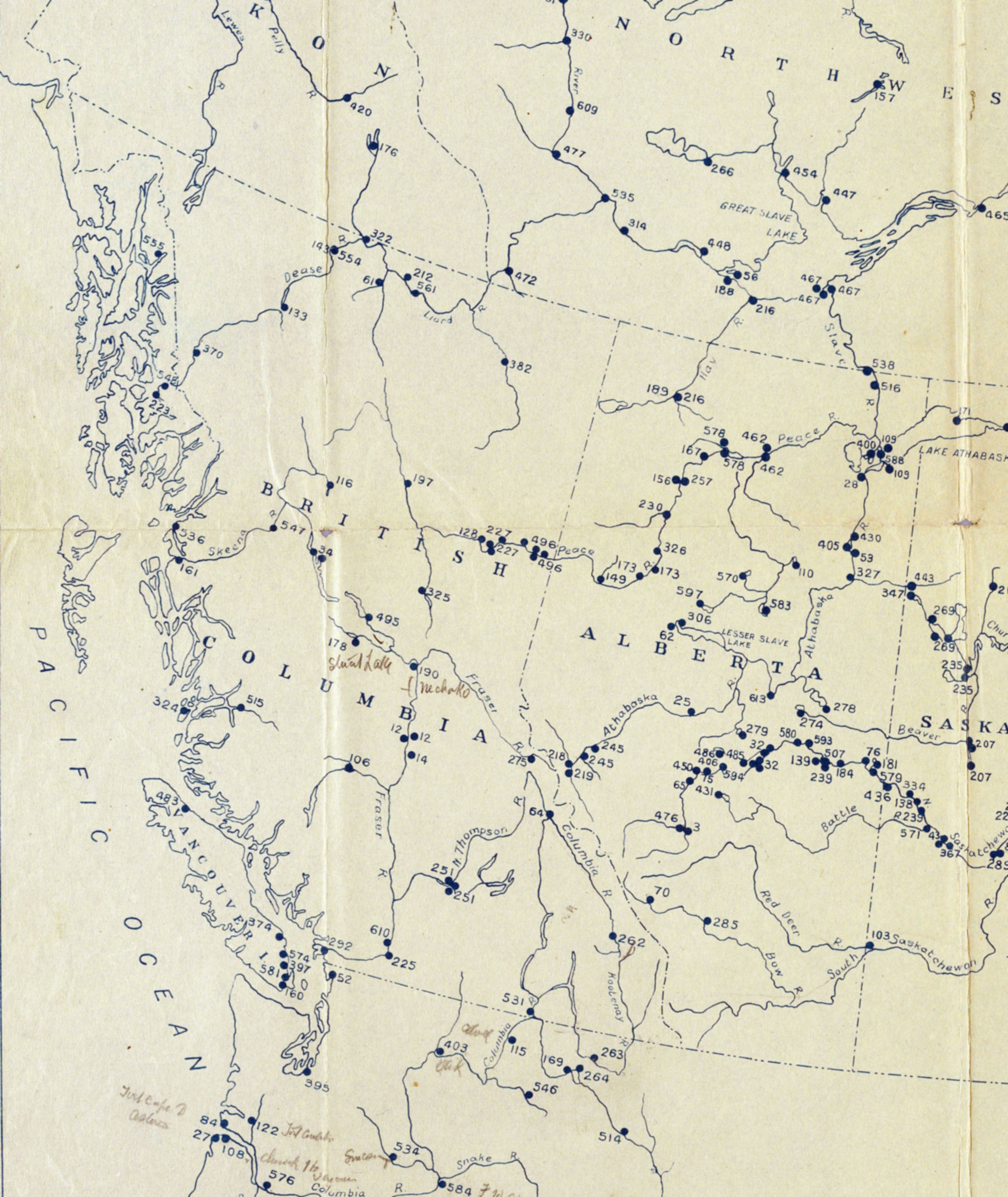

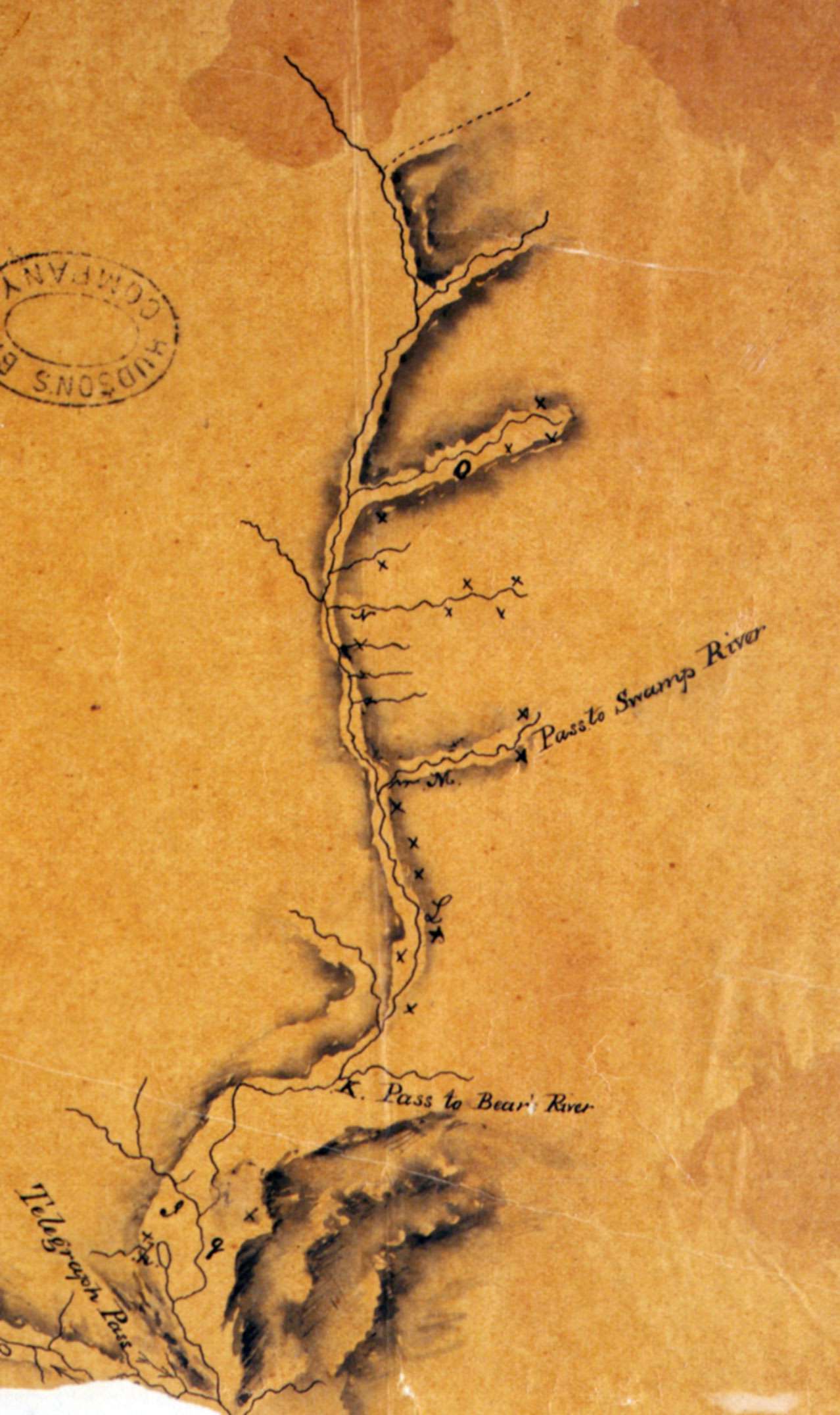

David Thompson is famous for his early exploration and mapping of western Canada and the northwestern United States. From 1790 to 1812, he traveled the Northwest using a sextant and compass to record valuable navigational information. He used this information to make some of the earliest detailed maps of the northwestern U.S. and western Canada. Paradoxically, although his navigational skills gave Thompson his claim to fame, they are poorly understood by both historians and geographers. How did he calculate his latitude and longitude, and how accurate was he? In this issue, I will use examples from Thompson’s notes to illustrate and explain the navigational methods that he used.

The case study examines Thompson’s journey from Boggy Hall [on the North Saskatchewan River] to the Whirlpool River, from October 19, 1810, until January 7, 1811. This is an important period because Thompson was near the end of his fur trade career (he retired in 1812) and had twenty years of navigational experience behind him. He was about to make two of his most important journeys: crossing the Athabasca Pass and descending the Columbia River to its mouth.

Synopsis of David Thompson’s Navigational Routine

Upon arrival at a new camp, Thompson would try to obtain an accurate latitude. If possible, he would observe a meridian transit of the sun (‘noon sight’). If this was not possible, he would make two observations of the sun one hour apart, which he would then use to compute a latitude with the double altitude method.

If the moon was in a convenient location, Thompson would observe the distance between the moon and the sun. Then, within half an hour or so, he would observe the altitude of the sun — a ‘time shot’. When making these lunar distance observations, he checked the index error of his sextant to make sure that it had not changed.

Using the observed altitude of the sun, the latitude computed earlier, and the declination of the sun as determined from the nautical almanac for the approximate Greenwich time as based on his dead reckoning longitude of the observation, Thompson computed the local apparent time. He then reset his watch to the correct local apparent time. This helped to ensure that he did not miss the next day’s noon sight due to the inaccuracy of his watch.

Sometimes, Thompson would note the compass bearing to the sun at the instant of the time shot. From his knowledge of his latitude, the sun’s declination, and the observed altitude, he could compute the sun’s true bearing (azimuth). The difference between the true bearing and the magnetic compass bearing was the magnetic variation (declination) at his position.

From his knowledge of his latitude, the local apparent time, and the declination of the sun, he then computed a close approximation of the sun’s altitude at the instant of the lunar distance observation. Then, from his knowledge of the local apparent time, his latitude, the declination of the moon based on his approximation of the time in Greenwich, and the difference in the right ascensions of the sun and the moon at the approximate Greenwich time of his observation, he computed a close approximation of the true altitude of the moon at the instant of the lunar distance observation.

From the close approximations of the moon’s and sun’s altitudes, combined with a highly accurate observation of the lunar distance, he then ‘cleared the distance’ of the effects of refraction and lunar parallax to determine an accurate true lunar distance between the sun and the moon for the local apparent time of the observation. He then used the nautical almanac to determine the apparent time in Greenwich at which the moon would be at the distance that he observed. The difference between his local apparent time and the apparent time in Greenwich, converted to degrees, resulted in his longitude.

Thompson also used the stars to compute lunar distances and double altitudes. The techniques are generally the same, but with a slight complication for the computation of local apparent time.

Gottfred explains the references to obscure techniques of navigation, and recalculates positions based on Thompson’s observations. “Over the last ten years I have used my own sextant under many different conditions to replicate all of the techniques that Thompson used…. I feel that it should be generally safe to assume that any latitude by meridian transit observation would be correct within 1½ nautical miles, and any latitude from a double altitude observation should be correct to within 2 [nautical miles],” he writes.

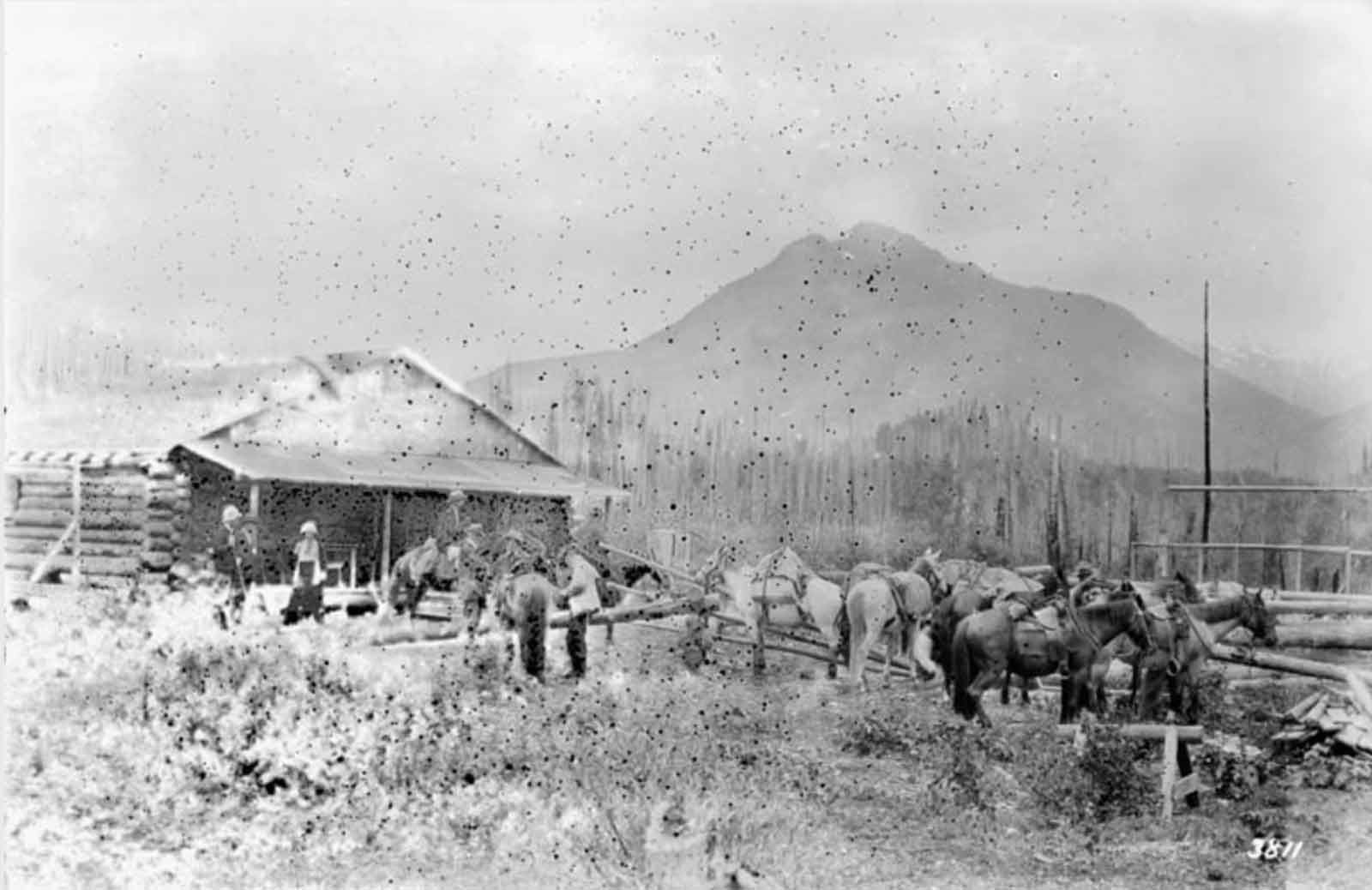

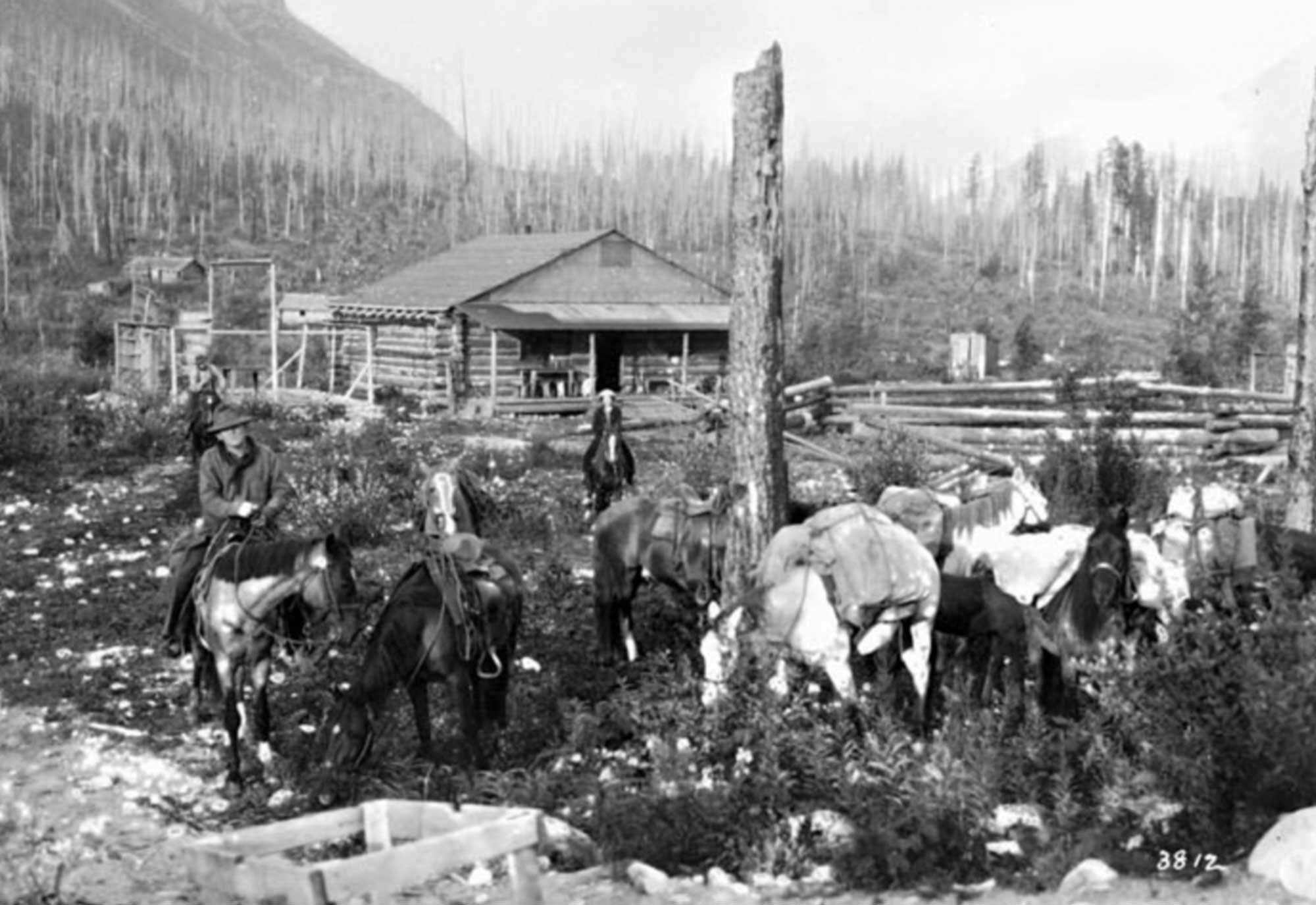

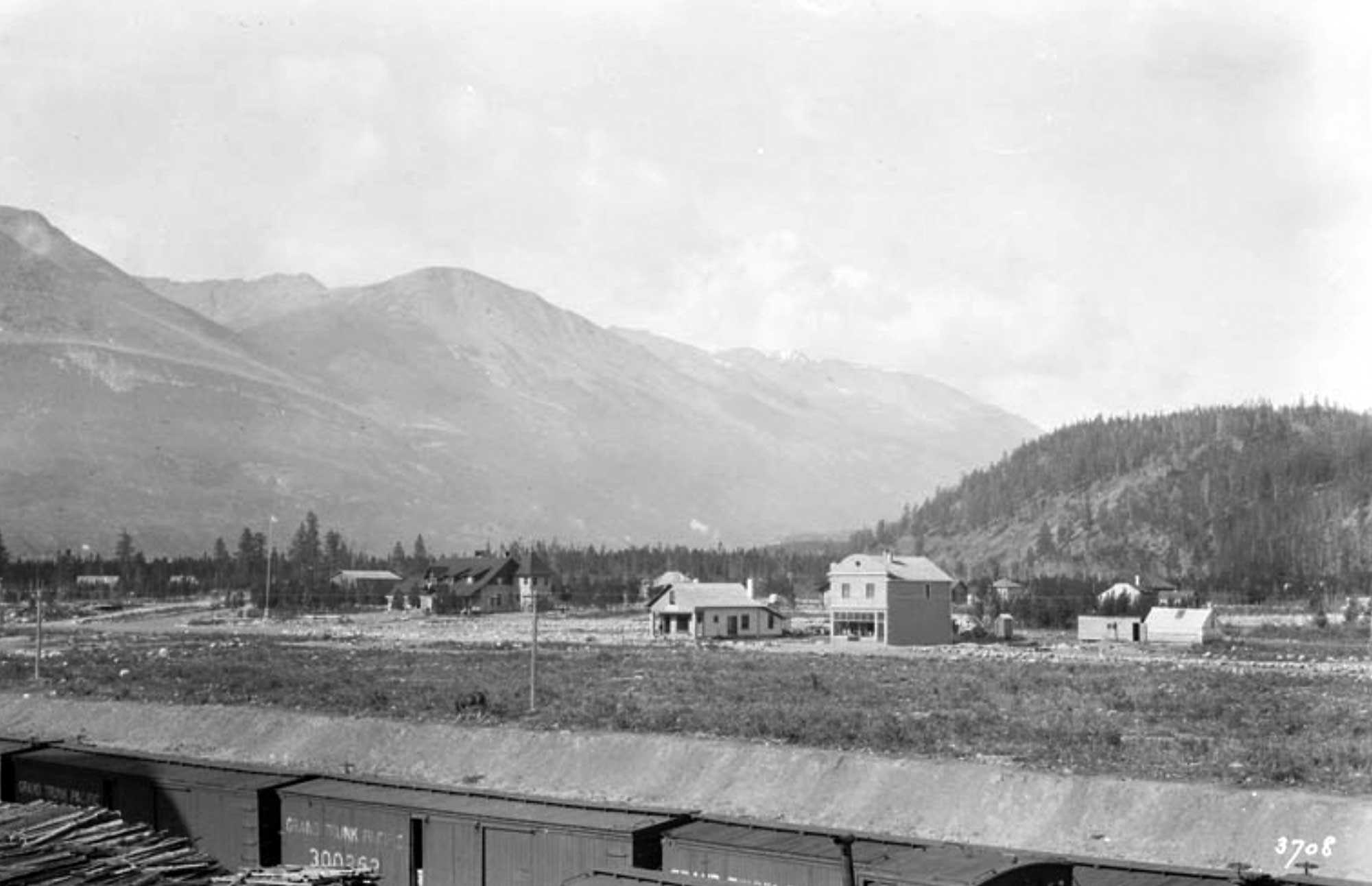

![Press Excursion Party at Summit [Yellowhead Pass] Photo: William James Topley, 1914](/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/topley-excursion-party.jpg)