In 1917, while serving in the Canadan Army Medical Corps in France,

George R. B. Kinney [1872–1961] wrote to Arthur Hinks, the secretary of the Royal Geographical Society in London, that he would be pleased to deliver a lecture on mountaineering in the Canadian Rockies, illustrated by “100 choice colored lantern slides, second to none (by report), and taken from my own negatives.… Mine are the original photographs taken of these hither to unexplored regions, and names like ‘Berg Lake,’ ‘Tumbling Glacier,’ ‘Robson Glacier,’ ‘Mt. Rearguard,’ ‘the Helmet,’ and ‘the Extinguisher’ that now have a permanency, were my suggestions, while Dr. Coleman gave the name of Lake Kinney on Mt. Robson’s western foot.” [

1] Kinney delivered the lecture in January 1919, and was subsequently elected a Fellow of the RGS.

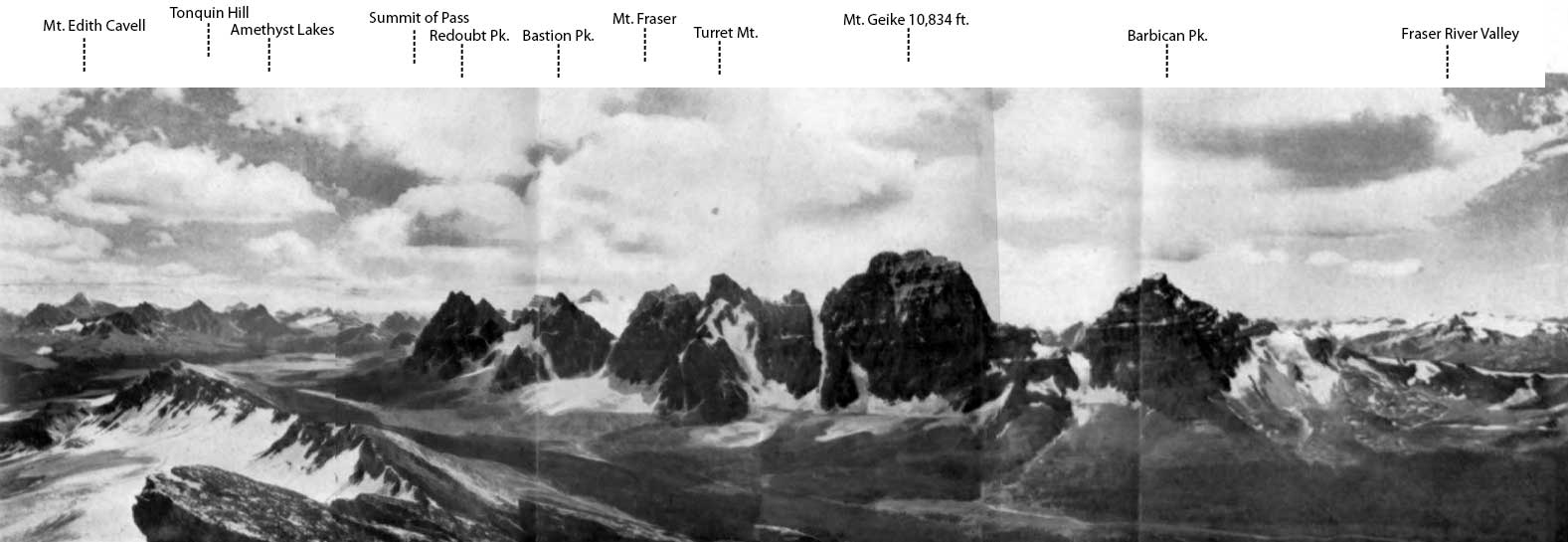

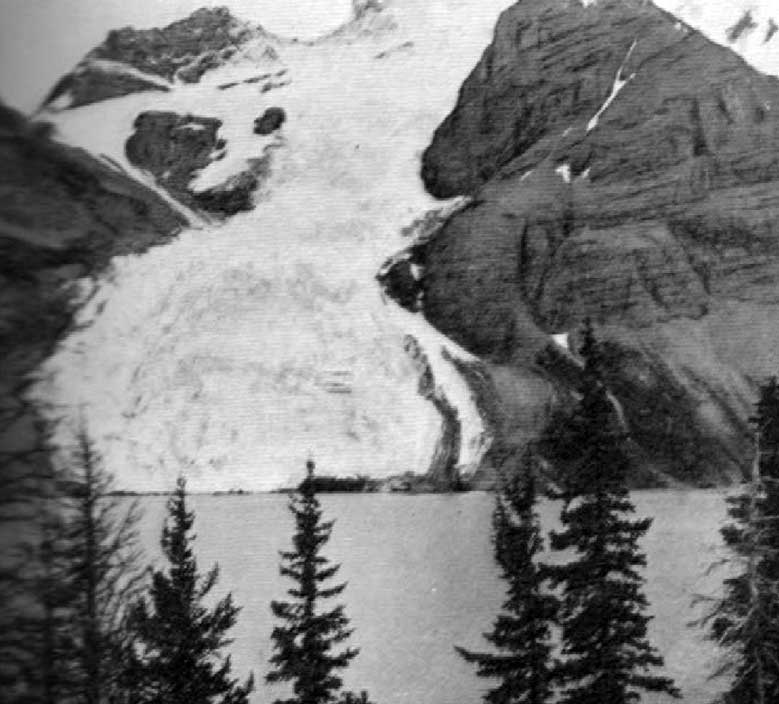

Kinney had accompanied Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939] and Coleman’s brother Lucius on the first mountaineering expedition to Mount Robson in 1907, when they approached from the Fraser River side and got little further than Kinney Lake. They returned in 1908, guided by Adolphus Moberly [1887– ?] and John Yates [1880– ?], who took them up the Moose River valley and approached Robson from the north. They became the first people to report on Berg Lake, Tumbling Glacier, Robson Glacier, Rearguard Mountain, The Helmet, and Extinguisher Tower, features Kinney named after their appearances.

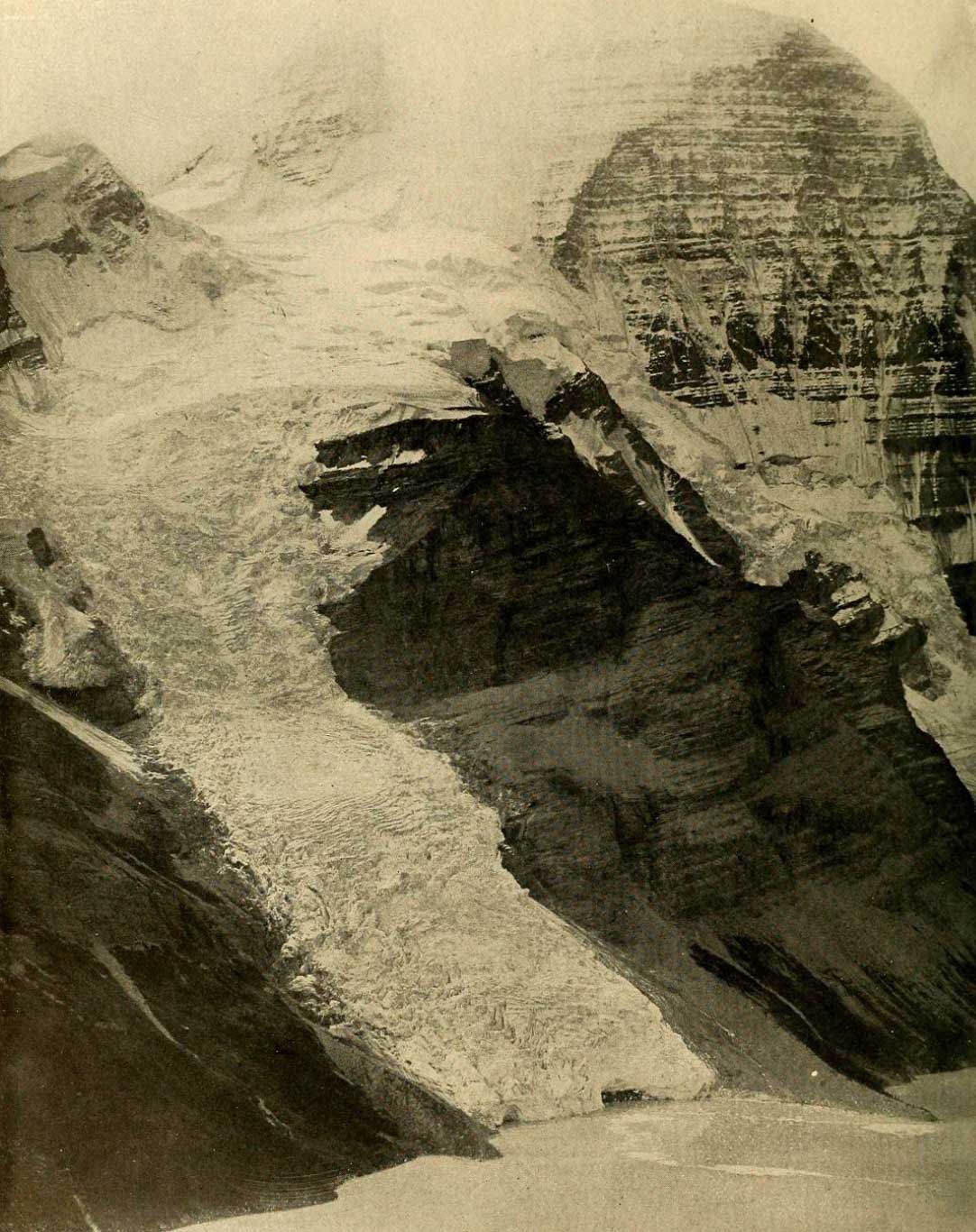

“From the elevated ice-field, fed by avalanching snows from the sides of Robson, a gigantic ice cascade tumbles down rock precipices and buries its nose in the waters of Berg Lake,” wrote Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945] after his 1911 visit. “At frequent intervals great chunks of ice break off with a report like cannon, and, bounding and rattling down the steep incline, plunge into the clear water of the lake. Dr. Coleman has named the overhanging ice-fall ‘The Blue Glacier,’ The term is not strong enough: ‘Tumbling Glacier,’ though not so euphonious, is a better name to express the activity of such a unique feature.” [2]

“Blue Glacier is a wonderful stream of slipping, sheering, blue, green, and white ice. Why it does not slip and slide as a whole down into Berg Lake is one of the unsolved secrets of this great mountain,” wrote Charles Doolittle Walcott [1850–1927] in his report on the 1912 Smithsonian expedition to Mount Robson. [3]