Flows E from Williston Lake into Alberta, thence NE into Slave River

56.1453 N -120 W — Map 94A/1 — Google — GeoHack

Official in BC – Canada

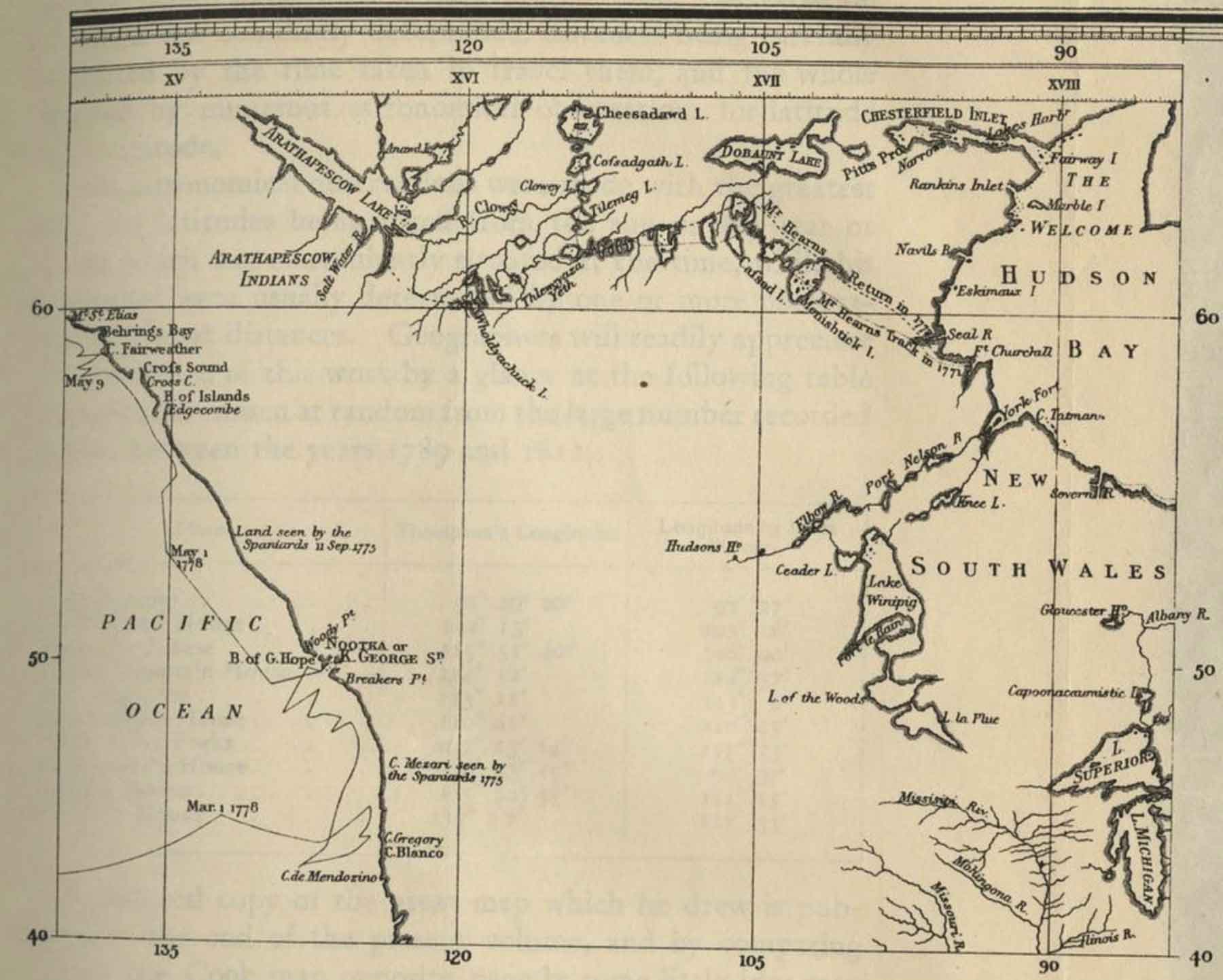

Aaron Arrowsmith’s map North America 1795

Mackenzie’s map North America 1803

David Thompson’s map North-West Territory of the Province of Canada 1814

John Arrowsmith’s map BC 1859

Trutch’s map of BC 1871

On Turnor map, 1790, as “Beaver Indian river by the Canadians called the Peace River” (18th Report of the Geographic Board of Canada, 31 March 1924). Identified as “Unjigah or Peace River” in Alexander Mackenzie’s journal (Voyage to the Pacific… 1793 p.319). Identified as “the great Unjigah or Peace River” by G.M. Dawson (Geological Survey Report 1879-80, p51B).

“….we came to the Peace Point [near Lake Athabasca in NE Alberta] from which, according to the report of my interpreter, the river derives its name. It was the spot where the Kristeneaux [Cree] and Beaver Indians settled their dispute. The real name of the river and point being that of the land which was the object of contention. When this country was formerly invaded by the Knisteneaux, they found the Beaver Indians inhabiting the land about Portage la Loche; and the adjoining tribe were those whom they called Slavey. They drove both these tribes before them; when the latter proceeded down the river from the Lake of the Hills [Lake Athabasca], in consequence of which that part of it obtained the name of the Slave River. The former proceeded up the river, and when the Kristeneaux made peace with them, this place was settled to be the boundary.” (Alexander Mackenzie, Voyage to the Pacific… 1793, partially reprinted in the 18th Report of the Geographic Board of Canada, 31 March 1924.)

Peter Pond’s maps of 1785 and 1787 refer to it as the “River of Peace”. Other names have included Un-ja-ga/Unjigah, as recorded on a map to accompany Mackenzie’s “Voyage to the Pacific… 1793”. It apparently means Large River in the Beaver language. In 1927, Father Morice, OMI, corroborates this translation by saying the Peace River was known to the Sekani Indians as Thû-tcî-Kah, or Water Great (or Important) River. Another source stated it was a translation of the Slavey word Chin-ch-ago, meaning Beautiful River. The Fort Chipewyan Hudson’s Bay Company post journal of 1822 also refers to it as Rivière de Brochet, referring to the northern pike which were likely found in the river.

Peace River was known as the unijigah of which “peace” is the translation. The Sekani, who dwelt further up the river, knew it as isetaieka, “the river which runs by the rocks,” a reference to its passage through the Rockies. (see “Peace River Was Old Indian Boundary Line” National Resources Canada, December 1927 clipping). Headwaters in British Columbia at 56º01′ – 122º12′ on map 94 B/1. Mouth in Alberta at 59º00′ – 111º25′ on map 74 L/14.

“The exact original meaning of the Indian word “Unchaga” or “Unchagah” or “Unjigah” is not certain. “Unchagah” as the word is usually given, has crept into the everyday language of the Peace River country. In its English translation, “Peace” it is both the name of a great river and of a vast territory. Apparently it is accepted by both of the peoples now known as Beaver Indians and by the Crees, although the last “prophet” of the Halfway Reserve, Charlie Yahey, did not recognize it. One would assume, then that the Western Beavers were not involved in the incident that conferred the name on the region. The name “Unjaga” was first officially used, as far as we know, by an Anglican Missionary who built a small mission near the old 1803 trading post close to present day Fort Vermilion. Reverend Garrioch, a true son of the country, liked the Indian name, meaning “Peace”. Bishop Young renamed the place the Irene Mission, since, being a classical scholar from England, he knew that “Irene” also meant “Peace”. Fortunately “Irene” didn’t stick!… In the form “unajigaensis” it appears in the scientific or Latinized names of natural history or fossil specimens meaning that the form was first found or identified in this area, or is peculiar to it. It is a “Peace River area thing,” and as such names are recognized worldwide in science… The location of Peace Point, still so-called on maps of the lower Peace River, marks the scene of the great conference where the pipe of peace was smoked, ending the active wars (but not the local squabbles and hostilities) of the Beavers and the Crees. The Peace River runs almost north-south in the vicinity of Peace Point. The Crees agreed to hunt only on the east side, leaving the west side as the Beavers’ hunting grounds. In ensuing years many Crees occupied the area south of the Peace as the Beavers withdrew further and further west…..” (excerpt from: “The Kelly Lake Metis Settlement” by Dorthea Calverley, published as article 01-068 in History is Where You Stand: a history of the Peace, a project of the Dawson Creek Municipal Library, School District 59, South Peace Historical Society, et al, based on materials in the Calverley collection: www.calverley.ca)

—-

Alberta Place Names:

Peace; point, Peace river; in the account of his voyage to thé Pacific in 1792-93, Mackenzie narrates that he entered the Peace river on 12 October and continues: “On the 13th at noon we came to the Peace Point, from which, according to the report of my interpreter, the river derives its name; it was the spot where the Knisteneaux [Crees] and Beaver Indians settled their dispute; the real name of the river and point being that of the land which was the object of contention. When this country was formerly invaded by the Knisteneaux, they found the Beaver Indians inhabiting the land about Portage la Loche; and the adjoining tribe were those whom they called slaves. They drove both these tribes before them; when the latter proceeded down the river from the Lake of the Hills [lake Athabaska] in consequence of which that part of it obtained the name of the Slave River. The former proceeded up the river; and when the Knisteneaux made peace with them, this place was settled to be the

1 boundary.’

Peace; river, Mackenzie river; the river has always been known to white men by this name and is so called by Alex. Henry, Peter Pond, Philip Turnor and Sir Alexander Mackenzie. Turnor’s map, 1790, has the inscription “Beaver Indian River, by the Canadians called Peace River,” and describes the land on both sides as “Beaver Indian country.” In Cree, Beaver Indian river is amiskwemoo sipi. Unjigah, meaning “large river”, is another Beaver Indian name mentioned by Mackenzie. The Sekani Indians, who dwell on its upper waters, call the river isetaieka-“the river which runs by the rocks,’ in allusion to its passage of the Rocky mountains.

“Peace River / Rivière de la Paix” is among the 75 “Pan-Canadian names,” large and well-known Canadian features and areas designated in Treasury Board Circular 1983-58 to require presentation in both official languages of Canada on federal maps.

- Canadian Board on Geographical Names. Place-names of Alberta. Published for the Geographic Board by the Department of the Interior. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1928. Hathi Trust

- British Columbia Geographical Names. Peace River