Earliest known reference to this name is 1911

Feature type: Railroad construction camp

Province: British Columbia

Location: Temporary camp at Yellowhead Pass

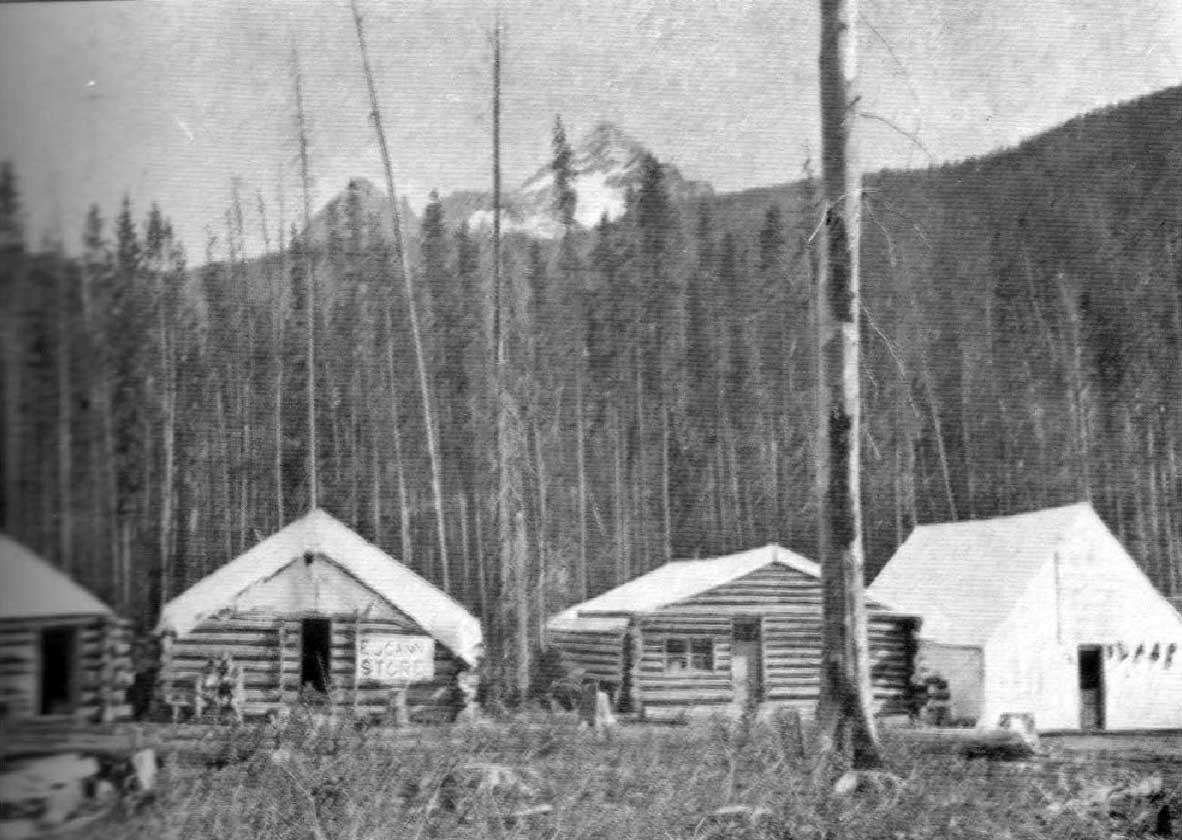

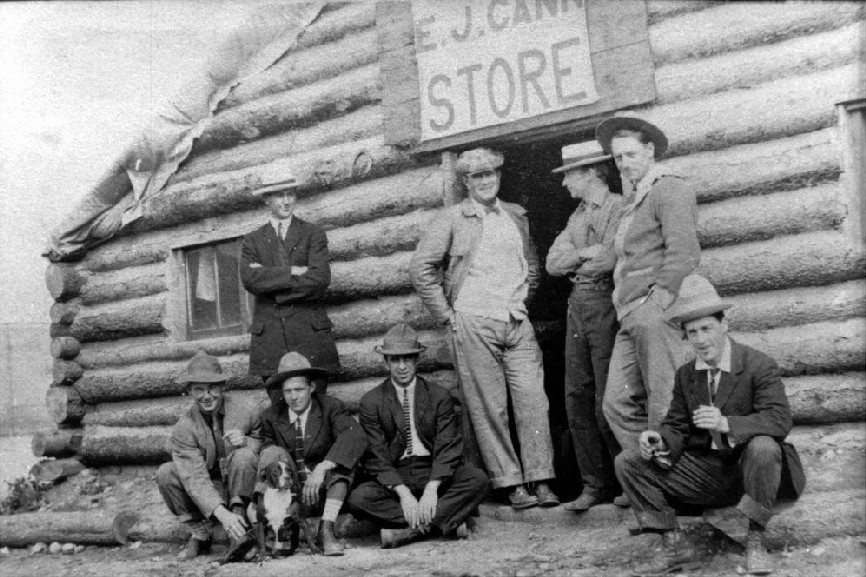

Summit City, Mile 1, GTP camp, E. J. Cann store, 1910-1911. L. J Cole photo. Donated by H. A. Cole. The E. J. Cann Store is also visible in the Byron Harmon photo.

Valemount & Area Museum

“The summit of the Pass, like that of the Main Divide at Stephen, is not very attractive,” wrote Arthur Wheeler of his visit in 1911. “The timber on the north side has been burned and is now an unsightly array of fallen and standing skeletons. It is sad to think that the beauty of this naturally charming spot has been for ever spoiled through reckless carelessness. In the eastern watershed, the Miette River, here a glacial torrent, comes from a canyon almost directly at the summit, and has cut in on the height of land to such an extent that the old channels that carried water westerly to the Pacific are still to be seen. Now, the flow has been confined entirely to the east by a line of crib-work the railway company has built to protect its property.”

The railway construction camp at Yellowhead Pass consisted of three or four make-shift stores, rough log buildings with canvas roofs, as many billiard and soft drink saloons, a railway contractor’s camp and a blacksmith shop. “The place was tough and rowdy,” Wheeler reported. “There was a shooting the night we were there, but no one seems to have been hurt. Outside of the refuse they accumulate and the despoiling of natural beauties, these places, though necessary at the time, are of little moment. They pass with the passing of the steel, and in all likelihood Summit City has passed since our party was there last August.”

Wheeler did not indicate “Summit City” on the map accompanying his report.

References:

- Wheeler, Arthur Oliver [1860-1945 ]. “The Alpine Club of Canada’s expedition to Jasper Park, Yellowhead Pass and Mount Robson region, 1911.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):9. Alpine Club of Canada