David Douglas was a Scottish botanist, best known as the namesake of the Douglas fir and for estimating the heights of Mount Brown and Mount Hooker to be about 17,000 feet above sea level. He worked as a gardener, and explored the Scottish Highlands, North America and Hawaii, where he died [1].

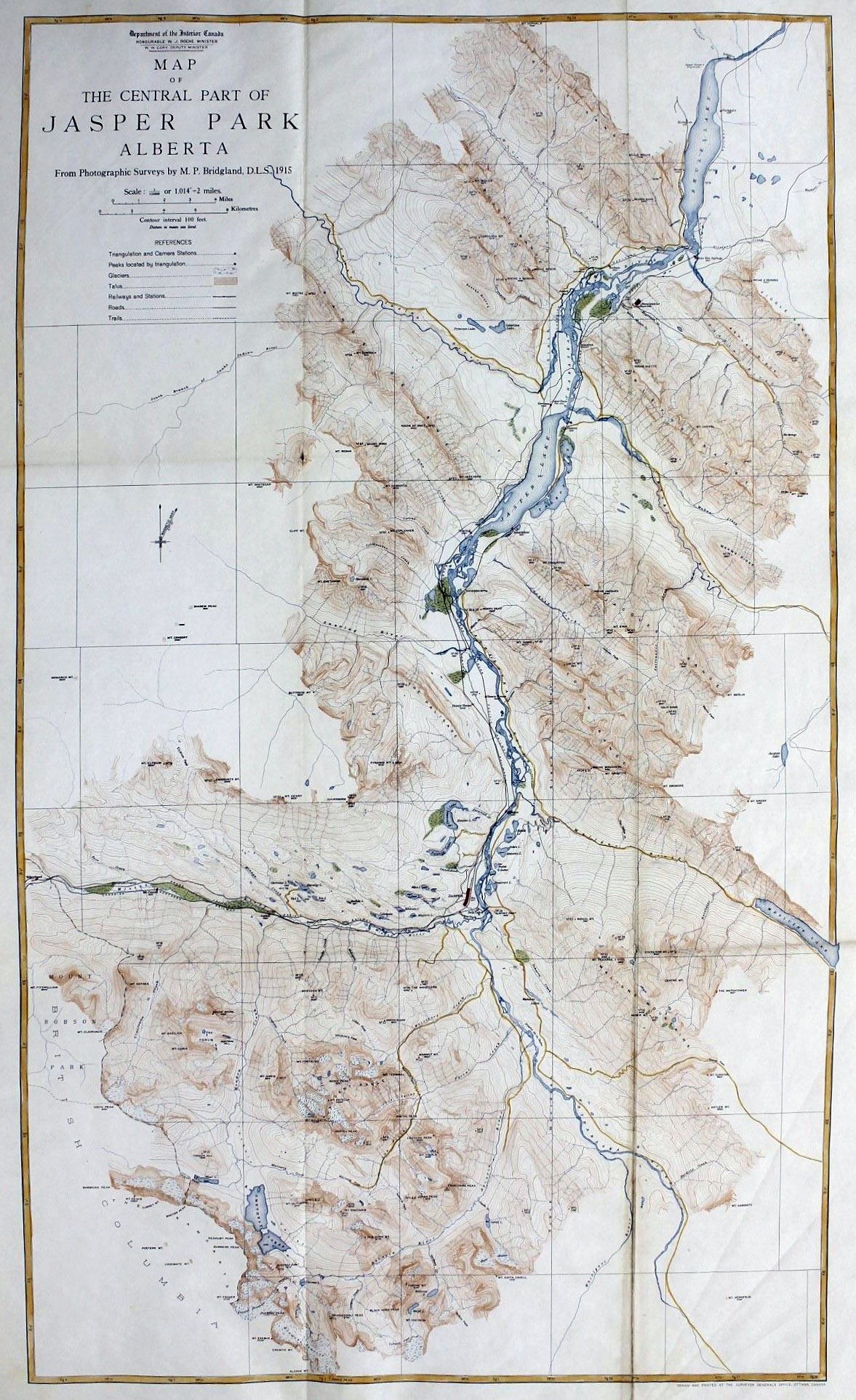

Douglas made three separate trips from Britain to North America. His first trip, to eastern North America, was from June to late autumn of 1823. The second was to the Pacific Northwest, from July 1824 returning October 1827. On 1 May 1827, Douglas crossed the Athabasca Pass:

After breakfast, about one o’clock, being well refreshed, I set out with the view of ascending what seemed to be the highest peak on the north. The height from its apparent base exceeds 6000 feet, 17,000 feet above the level of the sea. After passing over the lower ridge of about 200 feet, by far the most difficult and fatiguing part, on snow-shoes, there was a crust on the snow, over which I walked with the greatest ease. A few mosses and lichens, Andreae and Jungermanniae, were seen. At the elevation of 4800 feet vegetation no longer exists not so much as a lichen of any kind to be seen, 1200 feet of eternal ice. The view from the summit is of that cast too awful to afford pleasure nothing as far as the eye can reach in every direction but mountains towering above each other, rugged beyond all description; the dazzling reflection from the snow, the heavenly arena of the solid glacier, and the rainbow-like tints of its shattered fragments, together with the enormous icicles suspended from the perpendicular rocks ; the majestic but terrible avalanche hurtling down from the southerly exposed rocks producing a crash, and groans through the distant valleys, only equalled by an earthquake. Such gives us a sense of the stupendous and wondrous works of the Almighty.

This peak, the highest yet known in the northern continent of America, I felt a sincere pleasure in naming MOUNT BROWN, in honour of R. Brown, Esq., the illustrious botanist, no less distinguished by the amiable qualities of his refined mind. A little to the south is one nearly of the same height, rising more into a sharp point, which I named MOUNT HOOKER, in honour of my early patron the enlightened and learned Professor of Botany in the University of Glasgow, Dr. Hooker, to whose kindness I, in a great measure, owe my success hitherto in life, and I feel exceedingly glad of an opportunity of recording a simple but sincere token of my kindest regard for him and respect for his profound talents.” [2]

His third and final trip started in England in October 1829. On that last journey he went first to the Columbia River, then to San Francisco, then in August 1832, to Hawaii. Douglas died under mysterious circumstances while climbing Mauna Kea in Hawaii at the age of 35 in 1834. He apparently fell into a pit trap where he was mauled to death by a bull.

Athelstan George Harvey [1884–1950] published a biography in 1947 [3].