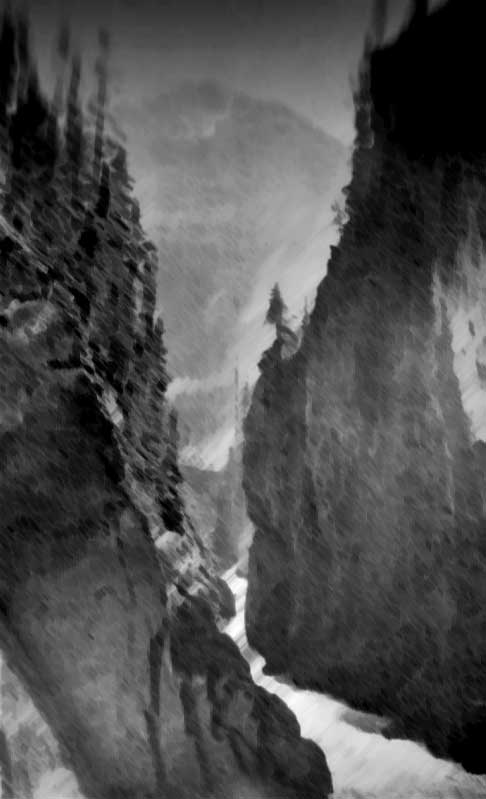

Canadian National Railway, N side of Moose Lake

52.95 N 118.8667 W — Map 83D/15 — Google — GeoHack

Earliest known reference to this name is 1912 (Wheeler)

Not currently an official name

Mile 38 in Albreda Subdivision (Jasper to Blue River as of 1977)

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway station built in 1913

Wheeler’s map Mount Robson 1912

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway ticket 1914

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway map ca. 1918

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway map 1919

Pre-emptor’s map Tête Jaune 3H 1919

Canadian National Railway map 1925

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway stations

Indicated on the map that Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945] composed after the 1911 Alpine Club of Canada–Smithsonian Robson Expedition.

“Topographical Map Showing Mount Robson and Mountains of the Continental Divide North of Yellowhead Pass” shows the line of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

Rainbow was among railway depots that were left vacant on the abandoned Grand Trunk Pacific Railway grade in 1917. Rainbow (GTP) was relocated to Red Pass junction in 1917.

Site of an internment camp for Canadians of Japanese descent during World War Two.

- Wheeler, Arthur Oliver [1860–1945]. “Topographical Map Showing Mount Robson and Mountains of the Continental Divide North of Yellowhead Pass to accompany the Report of the Alpine Club of Canada’s Expedition 1911. From Photographic Surveys by Arthur O. Wheeler; A.C.C. Director.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):8-81

- Bohi, Charles W., and Kozma, Leslie S. Canadian National’s Western Stations. Don Mills, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2002