Province: British Columbia

Location: Loops S off Hwy 5 near Valemount

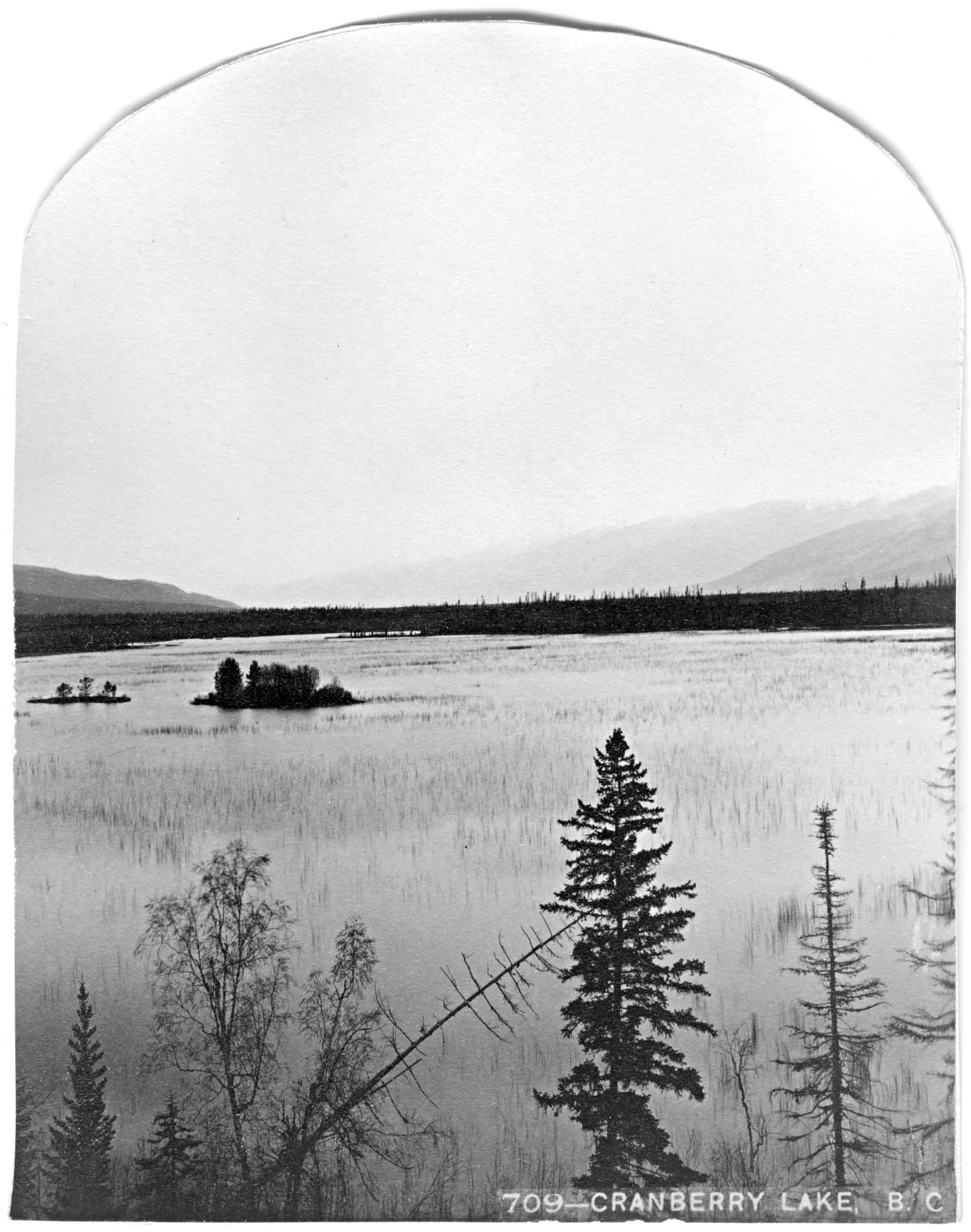

Cranberry Lake, BC. Benjamin F. Baltzly, 1871

McCord Stewart Museum

Hudson’s Bay Company director George Simpson [1792–1860] wrote in 1824,

At our Encampment [Boat Encampment, near the junction of Canoe River and the Columbia] fell in with a band of free Iroquois who have for several years hunted in the neighbourhood of Canoe River Cranberry & Moose Lake New Caledonia and the North branch of Thompson’s River.

Cranberry Lake, labelled on BC map 3H, 1919, was later drained and divided into lots (description of subdivision in 1924).

“Cranberry Lake, which is about seven hundred acres in area, lies on the divide between the McLennan and Canoe rivers,” wrote surveyor A. W. Johnson in 1912. “The lake apparently drains naturally into the McLennan, but it is a mere trickle. The lake is of beaver construction, and must have been quite recently a spruce-swamp, for there are many old roots under the water, which is nowhere more than three or four feet deep. It has nothing to justify its perpetuation as a lake, except that it makes a fine foreground for photographs of the surrounding mountains. So shallow that our paddle stirs up evil smells all the time, and while we were there, at any rate, avoided by ducks and geese, it would fulfill a higher destiny as a hay meadow. The water is warm in summer and almost stagnant; quite unfit to drink. Cranberry Lake is so called because there are no cranberries anywhere near it.”

The Cranberry Lake post office was open from 1913 to 1918, when it was changed to Swift Creek. In 1928, Swift Creek was changed to Valemount. There are less than ten cancellation marks known from the Cranberry Lake post office.

“Who remembers Cranberry Lake ?” asks an early settler. “It had a small island in the centre which grew swamp cranberries.” During the construction of the Yellowhead Highway in 1965, Cranberry Lake was filled in.

Location approximate. Origin unknown.

On August 22, 1911, Ernest C. Cox at Cranberry Lake (Valemount) wrote in his diary, “Saw Craig, the Fire Warden, Ed Garrett, and Kennedy.”

Stan Craig farmed at Croydon, east of Horsey Creek, and worked on the railroad atSwiftwater and other stations. He was listed in the 1943 Mount Robson post office directory as “section-man on the CNR,” a job he had held since 1918.

In the 1920s, to accommodate J. Bennett’s pole-cutting operation, Cariboo was moved to Mile 7 west of McBride. The station was renamed after Bennett and D. A. Craig, the section foreman. In 1928, Craibenn had four settlers and a government ferry.

“Curve (Coyote) Creek” labelled on BC map 3H, 1915. “Curve Creek (not Coyote Creek)” identified in the 1930 BC Gazetteer.

In 1824, George Simpson [1792–1860], heading for the Athabasca Pass, noted, “the track for Cranberry Lake takes a Northerly direction by Cow Dung River.” The Cow Dung River was the Miette and Simpson’s Cranberry Lake may have been preset-day Yellowhead Lake.

John Arrowsmith’s 1859 map shows “Cow dung L.” as the western lobe of Yellowhead Lake (the eastern lobe is labeled “Moose L.”).

In 1862, when the Overlander gold seekers crossed Yellowhead Pass (which they called Leather Pass) they camped on Cow Dung Lake. A year later, the lake was known to Milton and Cheadle as Buffalo Dung Lake.

The name “Cowdung L.” appears on B.C. Surveyor General Joseph Trutch’s 1871 map of British Columbia, between Moose Lake and the Yellowhead or Leather Pass.

“Cottonwood River,” the local name of Castle Creek, was known to travel writer Stanley Washburn [1878–1950] in 1909, among those names “given by the trappers.”

Committee’s Punch-bowl at the Source of the Whirlpool River. Hand-coloured lantern slide by Mary T.S. Schäffer. Photo taken in 1908

Archives Canada

At the very top of the pass or height of Land is a small circular Lake or Basin of water which empties itself in opposite directions and may be said to be the source of the Columbia and Athabasca Rivers as it bestows its favors on both these prodigious Streams. That this basin should send its Waters to each side of the Continent and give birth to two of the principal rivers in North America is no less strange than true both the Dr. & myself having examined the currents flowing from it East and West and the circumstance appearing remarkable I thought it should be honored by a distinguishing title and it was forthwith named the “Committee’s Punch Bowl.”

The Doctor was John McLoughlin [1784–1857]. The Committee was the executive of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Fur trader Alexander Ross [1783–1856], who was travelling with Simpson’s party, published this account in 1825:

On the top of this height was six inches of newly-fallen snow, and a small circular pond of water about twenty feet in diameter. This height I named after our Governor, Mount Simpson ; and the basin of water on its top, the Governor’s Punch Bowl. No elevated height in this country can present a more interesting prospect than that viewed from the top of Mount Simpson: to the west, in particular, it is of a highly picturesque character.

Fur traders paused at this natural campsite to drink a toast “to their Honours the Governors,” the governing committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company in London.

The Athabasca Pass forms the watershed between the two great river systems of the Athabasca and the Columbia, whose waters flow out at either end (a somewhat rare and remarkable phenomenon) of a small mountain tarn rejoicing in the name of “The Committee’s Punch-Bowl.” West and east of the tarn, forming the Titanic pillars of this natural gateway to the north, were said to be the two great peaks, Mount Brown and Mount Hooker.

— Stutfield 1903

A lake with this “rare and remarkable phenomenon” is called a bifurcation lake.