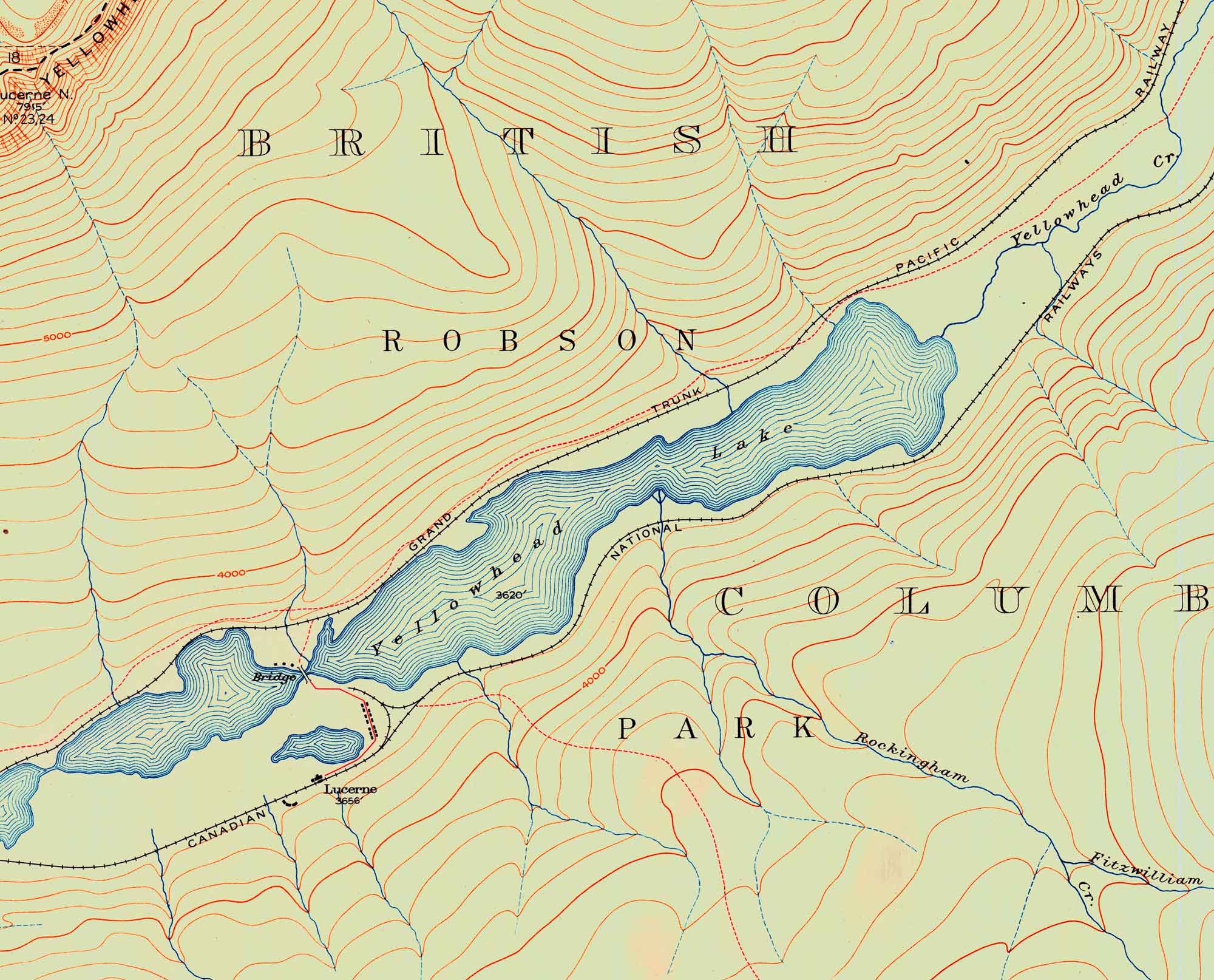

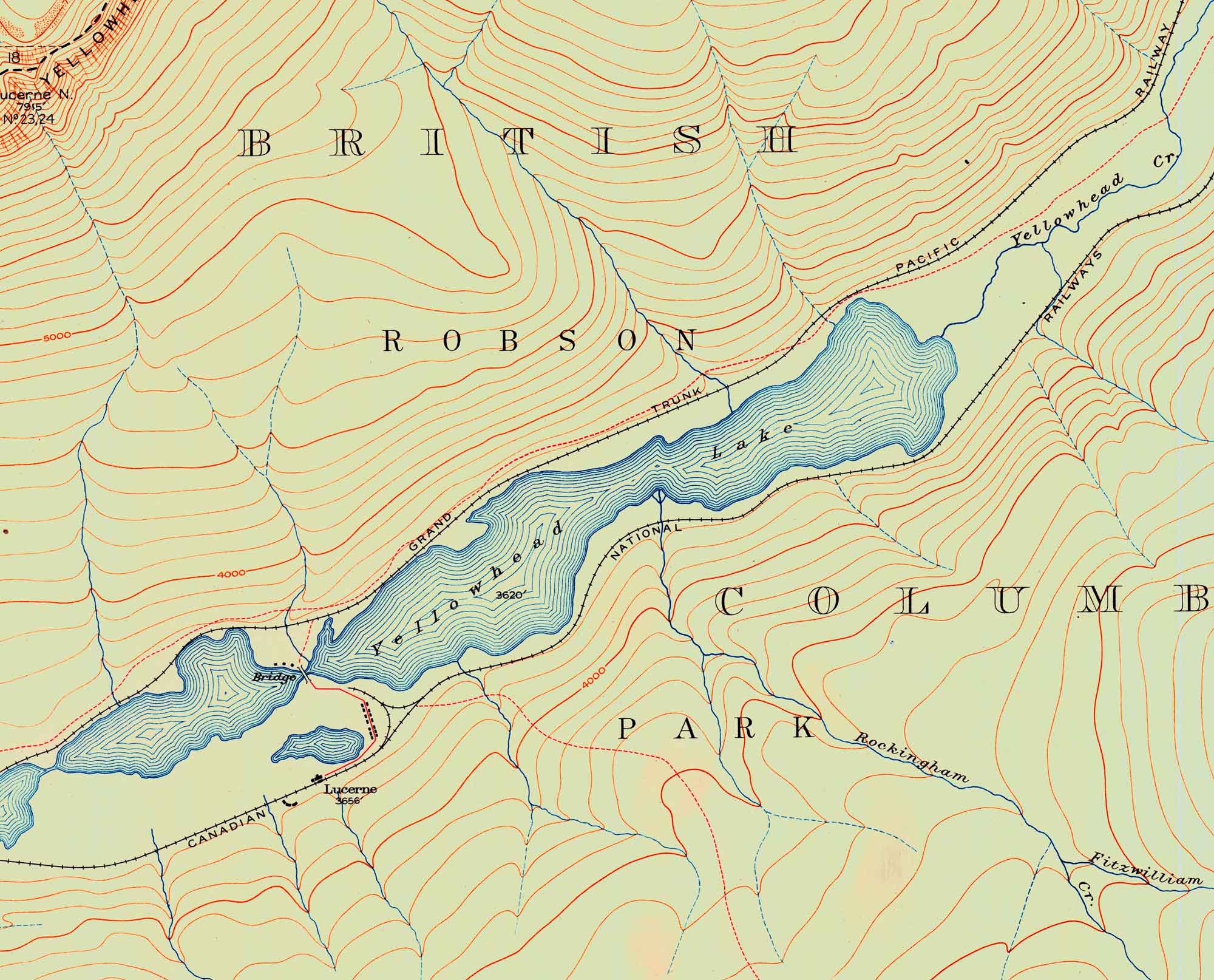

Yellowhead Lake. Surveyed in 1917. Boundary between Alberta and British Columbia. Detail.

Internet Archive

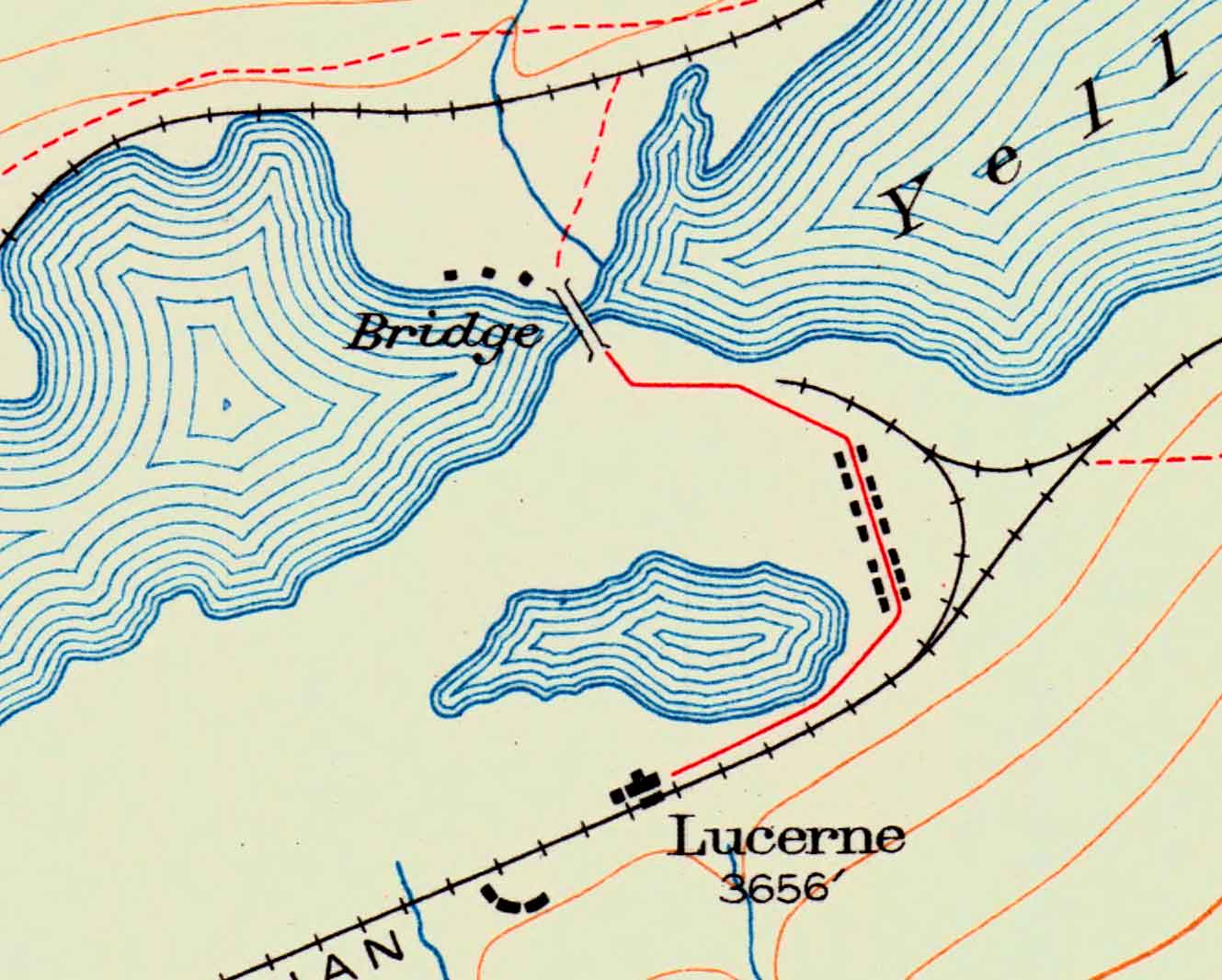

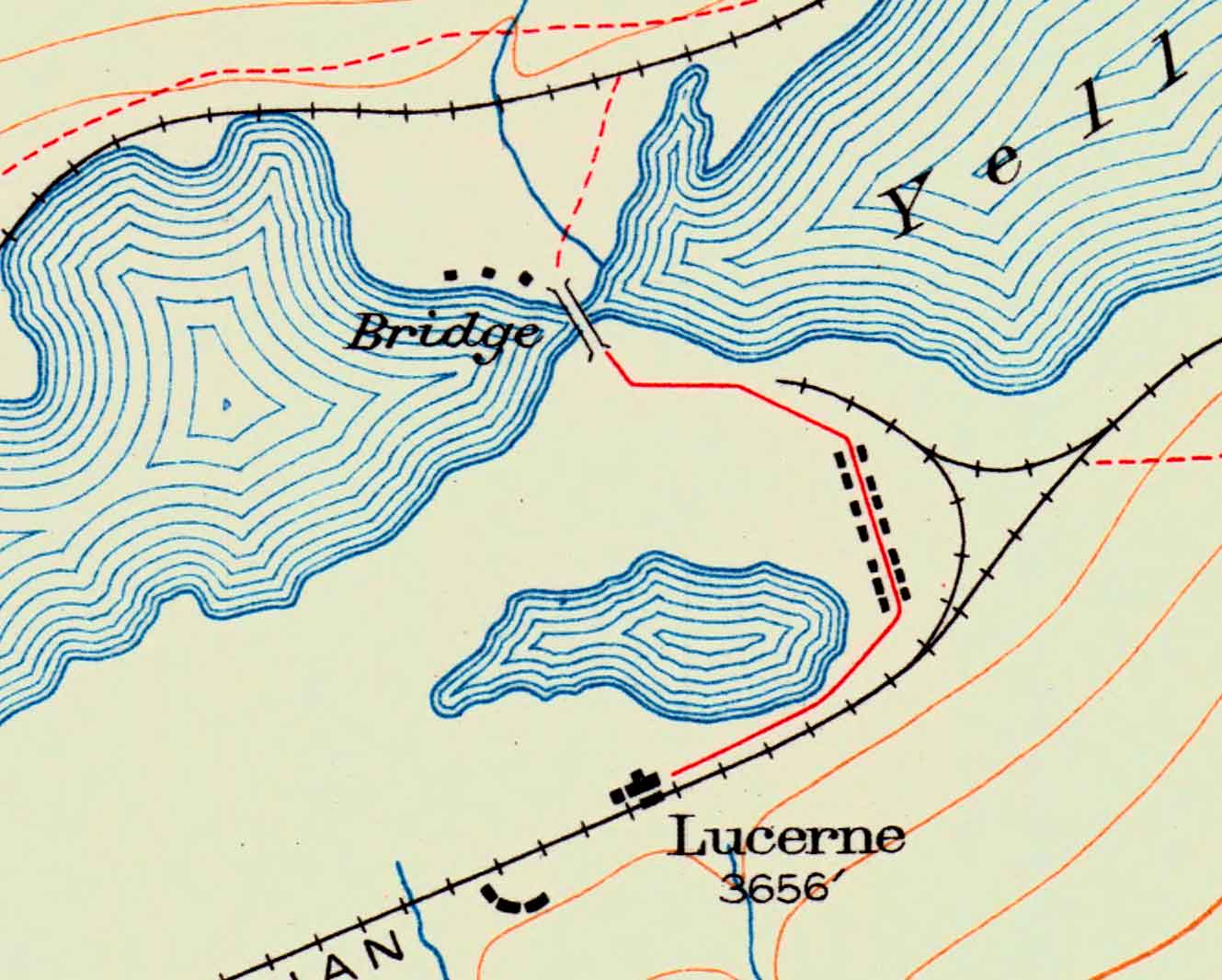

Lucerne. Surveyed in 1917. Boundary between Alberta and British Columbia. Detail.

Internet Archive

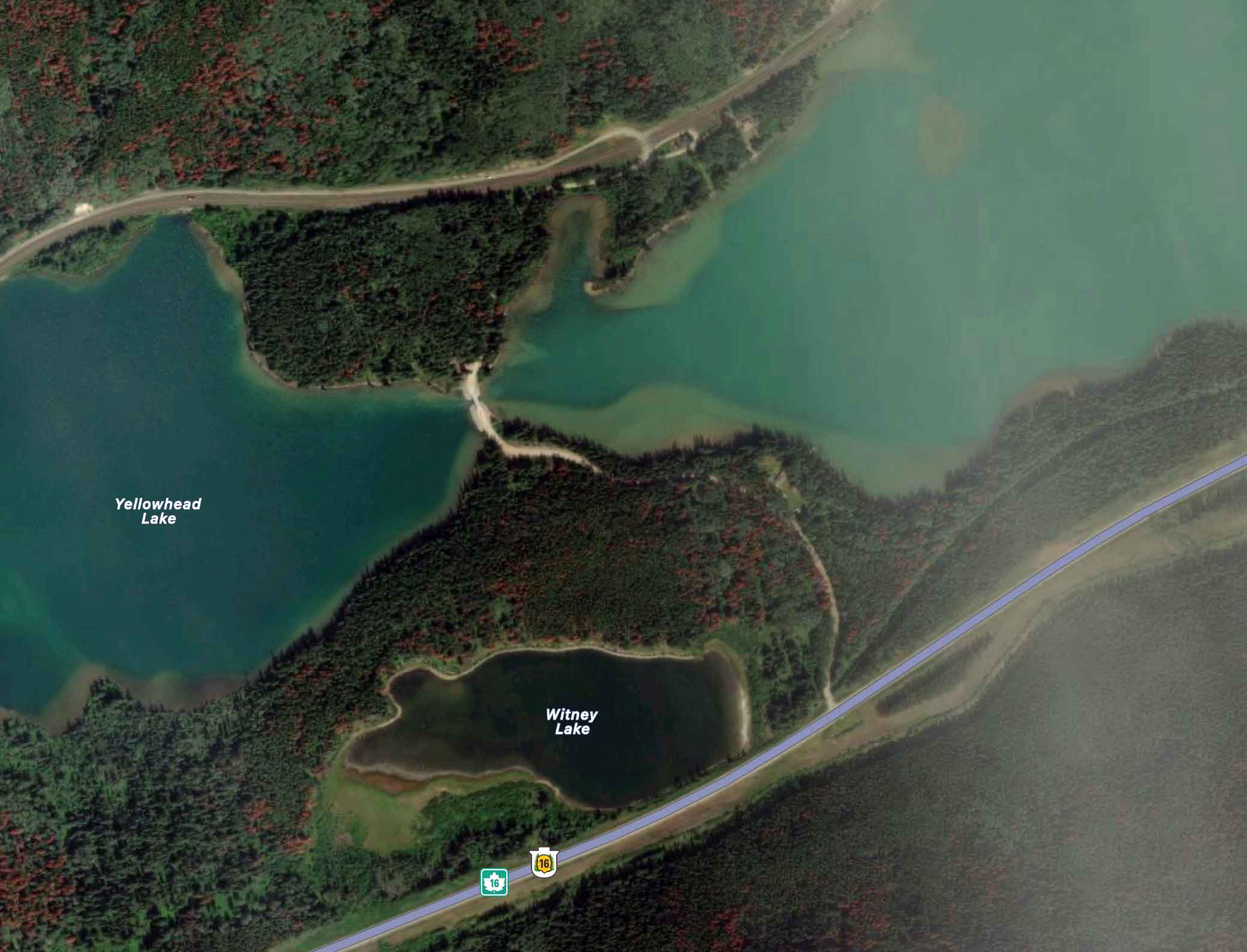

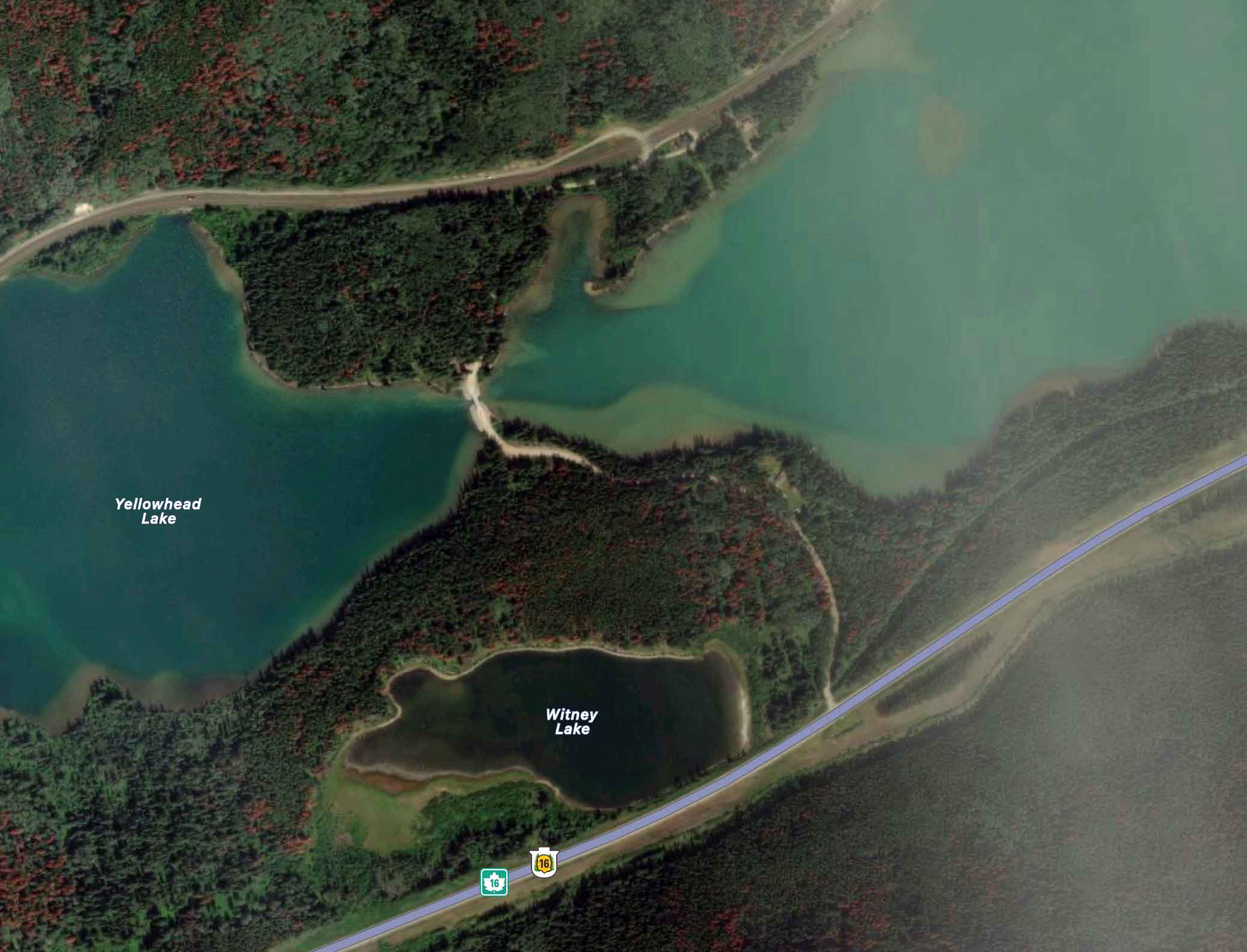

Current aerial view of Lucerne showing no structures on the south side of the lake and possible structures near the Canadian National Railway line north of the lake

Apple Maps

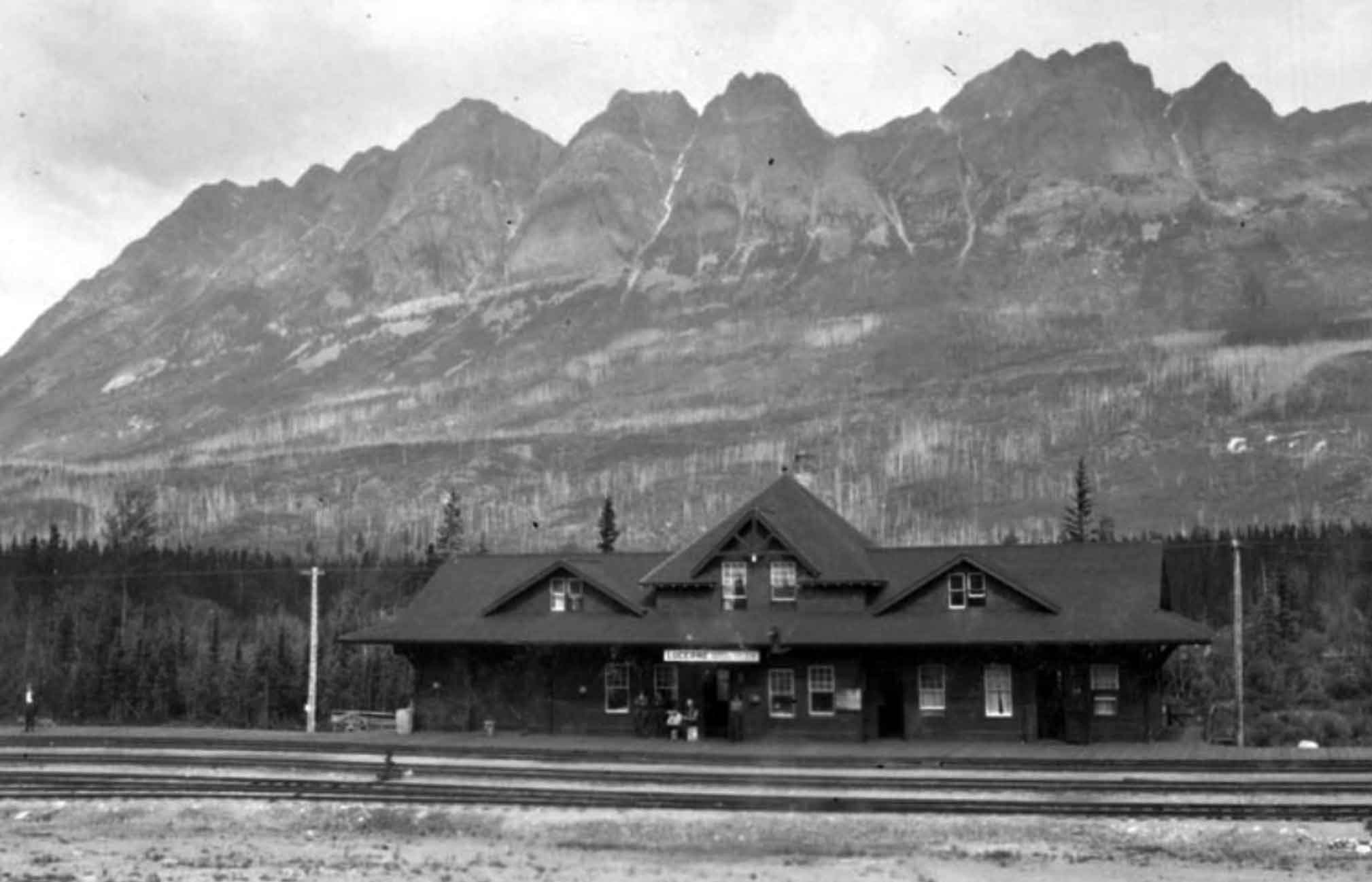

The Canadian Northern Railway yard in Lucerne, circa 1917

Parks Canada

The Canadian Northern Railway built their station at Lucerne on the south side of Yellowhead Lake by 1913. The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway had laid its track north of the lake the year before. Charles Bohi stated in 1977 that “the present Canadian National station at Lucerne is a ‘Type E’ structure built by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.”

Lucerne was a divisional point on the Canadian Northern and provided the nucleus of a town. After the two railroads were nationalized in 1921, Jasper was chosen as the divisional point of the new Canadian National Railway. At the time both towns had populations approaching 300. By the end of 1924 almost everyone had moved to Jasper, the rails of the yard had been taken up, and Lucerne became a whistle stop on the Canadian National line. The Lucerne railway station, as big as the Jasper station, was demolished after World War II.

Between Edmonton and the Yellowhead Pass the CNoR Lucerne and GTP built virtually parallel lines. was CNoR division point, and at one time had a Second Class depot. With nationalization and the combining of the CNoR and GTP lines, Lucerne lost its status as a terminal and the Second Class depot was removed.

During the Second World War, about 100 Japanese nationals were interned at camps at Lucerne, Rainbow, Moose River, Fitzwilliam, and Red Pass. As forced labor, they cleared a new right-of-way on sections of the Yellowhead Highway. In different groups they cut the timber off much of the road toward Tête Jaune Cache and along the river toward McBride on the one hand and toward Blue River on the other. As a diversion from their other activities, they built a tea house in the Lucerne camp and for several years it remained as a curiosity shown off by the few local people.

The Lucerne Station post office was open from 1914 to 1926; less than ten cancellation marks are known in collections. A post office was also open at Lucerne from 1942 to 1945; no cancellation marks between those dates are known to exist.