In 1917, while serving in the Canadan Army Medical Corps in France,

George R. B. Kinney [1872–1961] wrote to Arthur Hinks, the secretary of the Royal Geographical Society in London, that he would be pleased to deliver a lecture on mountaineering in the Canadian Rockies, illustrated by “100 choice colored lantern slides, second to none (by report), and taken from my own negatives.… Mine are the original photographs taken of these hither to unexplored regions, and names like ‘Berg Lake,’ ‘Tumbling Glacier,’ ‘Robson Glacier,’ ‘Mt. Rearguard,’ ‘the Helmet,’ and ‘the Extinguisher’ that now have a permanency, were my suggestions, while Dr. Coleman gave the name of Lake Kinney on Mt. Robson’s western foot.” [

1] Kinney delivered the lecture in January 1919, and was subsequently elected a Fellow of the RGS.

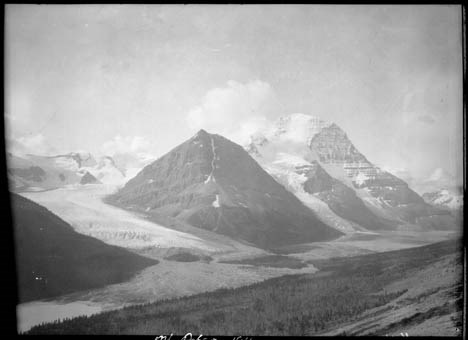

Kinney had accompanied Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939] and Coleman’s brother Lucius on the first mountaineering expedition to Mount Robson in 1907, when they approached from the Fraser River side and got little further than Kinney Lake. They returned in 1908, guided by Adolphus Moberly [1887– ?] and John Yates [1880– ?], who took them up the Moose River valley and approached Robson from the north. They became the first people to report on Berg Lake, Tumbling Glacier, Robson Glacier, Rearguard Mountain, The Helmet, and Extinguisher Tower, features Kinney named after their appearances.

By walking a hundred yards from our camp into the valley Mount Robson came into view during the rare intervals when the clouds drifted away, disclosing an imposing dome of white rising eight thousand feet above our valley, the lower part banded with courses of rock. Immediately behind our little grove a half-mile of glacier flowed, separating us from the cliffs of the Rearguard, one of the subordinate peaks, which reached a height of about nine thousand feet.

From his vantage on Mumm Peak during the 1911 Alpine Club of Canada–Smithsonian Robson Expedition, Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945] described the rugged ridge running from the centre of Mount Robson’s north-east face. “The ridge ends in a semi-detached rock mass, aptly named by Coleman ‘Rearguard.’”

Coleman did not claim to have named Rearguard.

Paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott [1850–1927] explored in the Mount Robson area in 1912:

Directly above Blue Glacier a point of rock was named by Dr. Coleman “The Helmet,” and the great black mountain in the center, which he called the “Rearguard,” is now given the Indian name of Iyatunga (Black Rock) (note: name approved by the Geographical Board of Canada, December, 1912.) [3]

“Iyatunga” is no longer official. No one seems to have used it except Walcott.

![Giant's Bath tub, Source of the Smokey [sic]. Mount Robson.

William James Topley, 1914](/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/topley-giants-bath-tub.jpg)

![East face of Mount Robson and The Helmet (background right). Photo: Byron Harmon [1918]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/wmcr-harmonb-v263-na-0955.jpg)