N of Fraser River near junction with Holmes River

53.275 N 119.9611 W — Map 83E/5 — Google — GeoHack

Earliest known reference to this name is 1912

Name officially adopted in 1994

Official in BC – Canada

A mountain prominent in the McBride skyline. Some say the rock formation at the summit resembles a beaver. This rock formation may be the reason that the adjacent Holmes River was first called “Beaver River.”

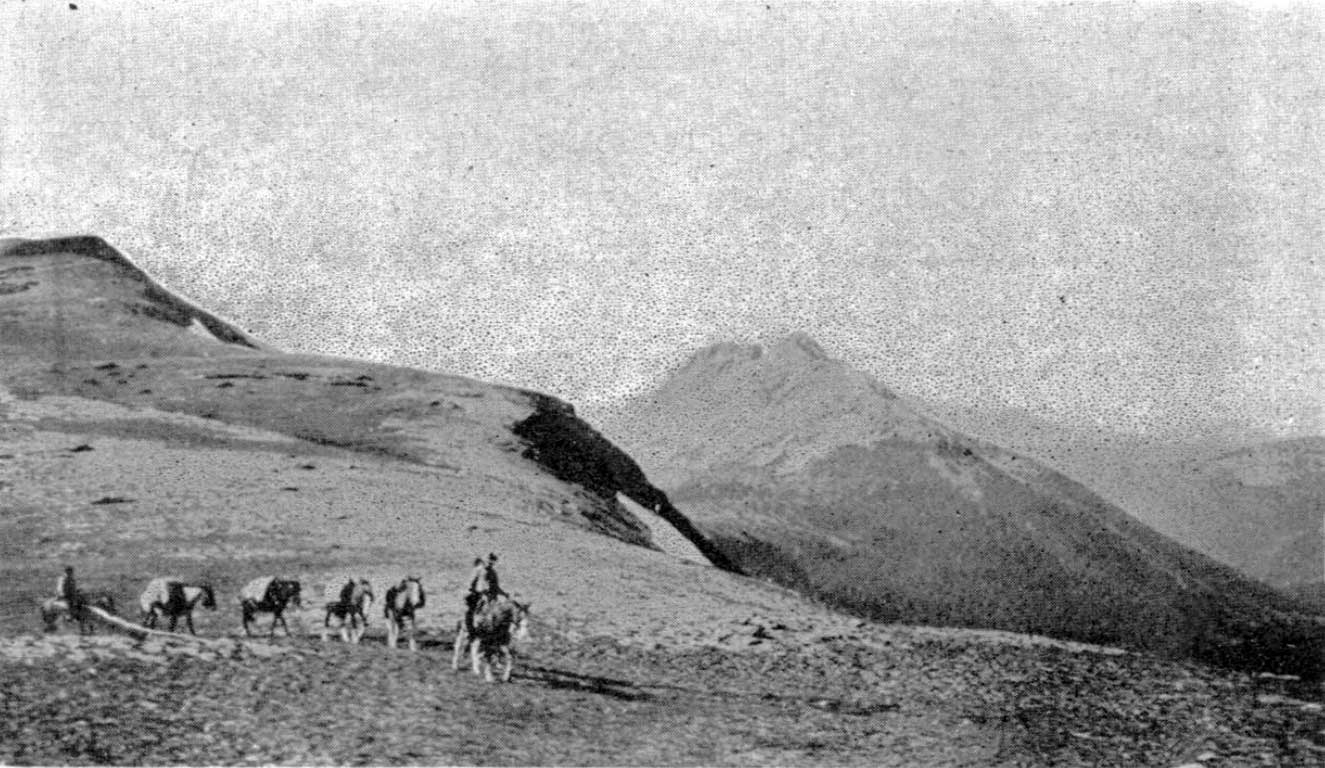

Designated as “Mammoth Mountain” on the Preliminary map of the Canadian Rocky Mountains between Jarvis Pass and Yellowhead Pass (Bull. Amer. Geog. Soc. Vol. XLVII, No. 7, 1915), showing the route followed by Mary Lenore Jobe Akeley [1878–1966] in August 1914, with guide Donald “Curly” Phillips [1884–1938].

- Washburn, Stanley [1878–1950]. Trails, Trappers and Tenderfeet in the New Empire of Western Canada. New York and London: Henry Holt, Andrew Melrose, 1912. Hathi Trust

- Jobe Akeley, Mary Lenore [1878–1966]. “Mt. Kitchi: A New Peak in the Canadian Rockies.” Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, Volume 47, No. 7 (1915):481-497, Map follows p. 496. JSTOR

- British Columbia Geographical Names. The Beaver