Flows W into Albreda River near Gosnell (railway point)

52.5008 N 119.115 W — Map 083D06 — Google — GeoHack

Name officially adopted in 1962

Official in BC – Canada

“Brûlé” means “burnt” in French. As used in the phrase of Donald “Curly” Phillips [1884–1938], “We lost the trail and had to cut through half a mile of brulé” [burnt forest]. Pioneers called a burned out area a “bob ruly,” from the French bois brulé.

During a 1909 trip across the Yellowhead Pass with Stanley Washburn [1878–1950], Lacombe guide Fred Stephens examined what was reported to be an excellent stand of timber in the upper Fraser River valley. It was found to be completely burnt over.

The hill was named by the Alberta-British Columbia Boundary Commission party of Wheeler and Cautley in 1921.

James Baker

Wikipedia

Named after Colonel James Baker [1830-1906], Provincial Secretary and Minister of Mines for British Columbia from 1892 to1898.

Adopted 5 March 1935 on Jasper Park south map. First labelled on a map published in 1896 (title not cited in BC files) (information provided by H. Nation, 1934).

Baker Creek is also the local name of Holliday Creek in the Fraser watershed.

On the 1919 map, the creek appears as “Holliday (Baker) Creek”

The name Baker is among those “given by the trappers,” according to Stanley Washburn [1878–1950] , who canoed down the Fraser River from Tête Jaune Cache to Fort George in 1909. (1)

The creek is perhaps named for Charlie Baker, who froze to death on Macleod Creek in January 1909. With three other men Baker had prospected the Goat River, and got lost returning to Barkerville.(2)

There is also a Baker Creek flowing into the Columbia River.

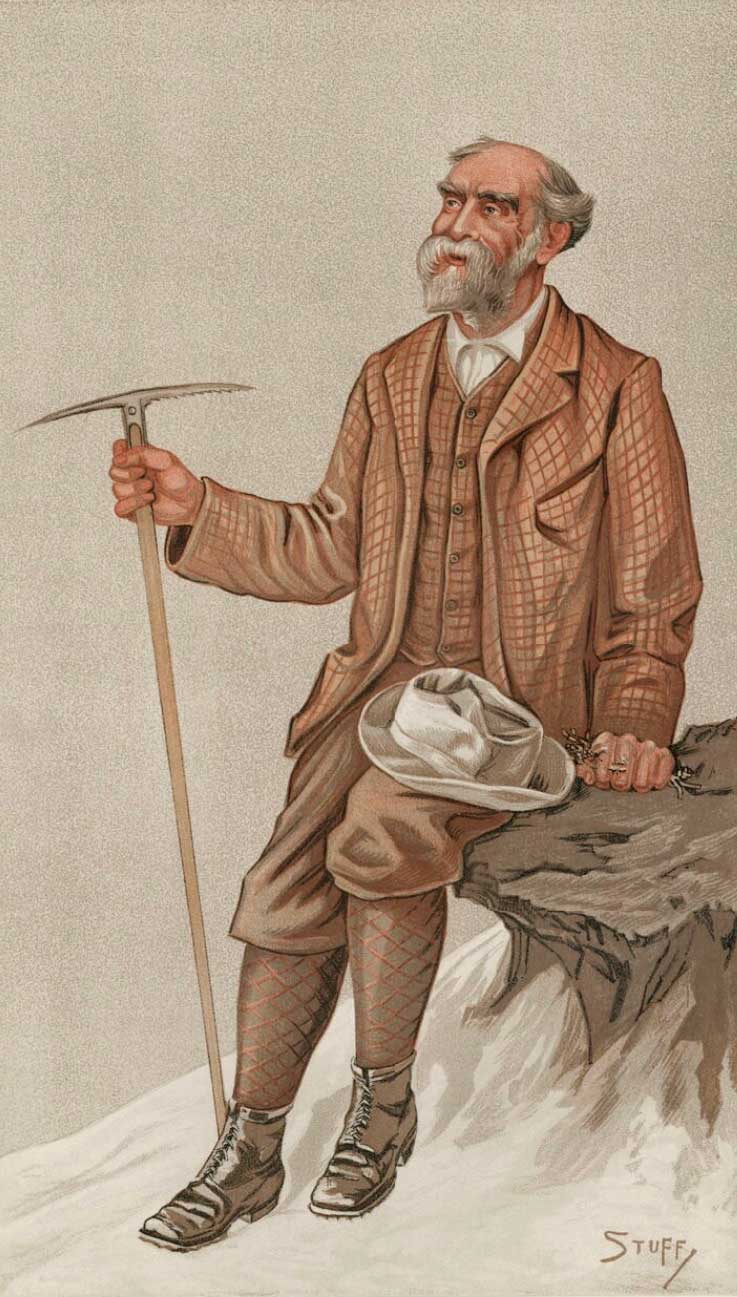

Privy Councillor, Professor and Politician. The Right Honourable James Bryce.

Published in Vanity Fair 25 February 1893

National Portrait Gallery (UK)

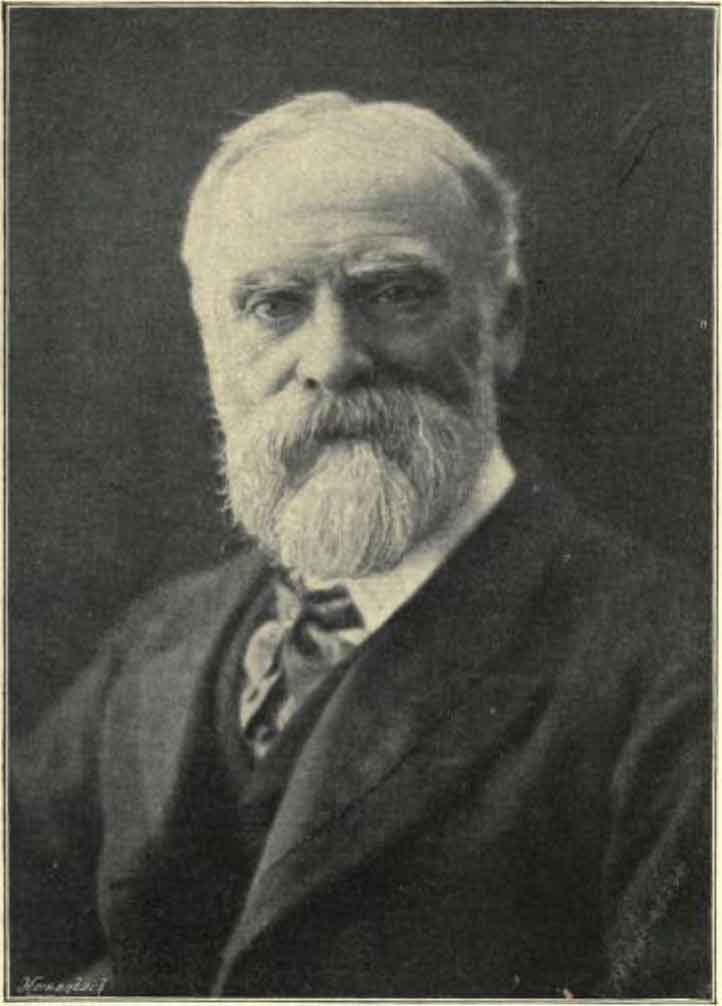

Right Hon. James Bryce

Cassell’s Universal Portrait Gallery

Named in 1898 by British alpinist John Norman Collie [1859–1942] after Rt. Hon. James Bryce (1838 – 1922), historian, diplomat, then-president of the Alpine Club (London); later Viscount Bryce, British Ambassador to United States, 1907-13.

Bryce’s chief contributions to historical and constitutional literature are The Holy Roman Empire The American Commonwealth.

Bryce was also an enthusiastic mountaineer; he explored the highlands of Hungary, Poland, and Iceland, and was one of the first climbers to scale Mount Ararat.

On July 15, 1928, Allen Carpé [1894–1932] “repeated the ascent of Albreda Mountain, previously climbed in company with Rollin Thomas Chamberlin [1881–1948] and A. L. (Pete) Withers on July 19, 1924.”

Named in association with Albreda Lake, a name dating to 1863.

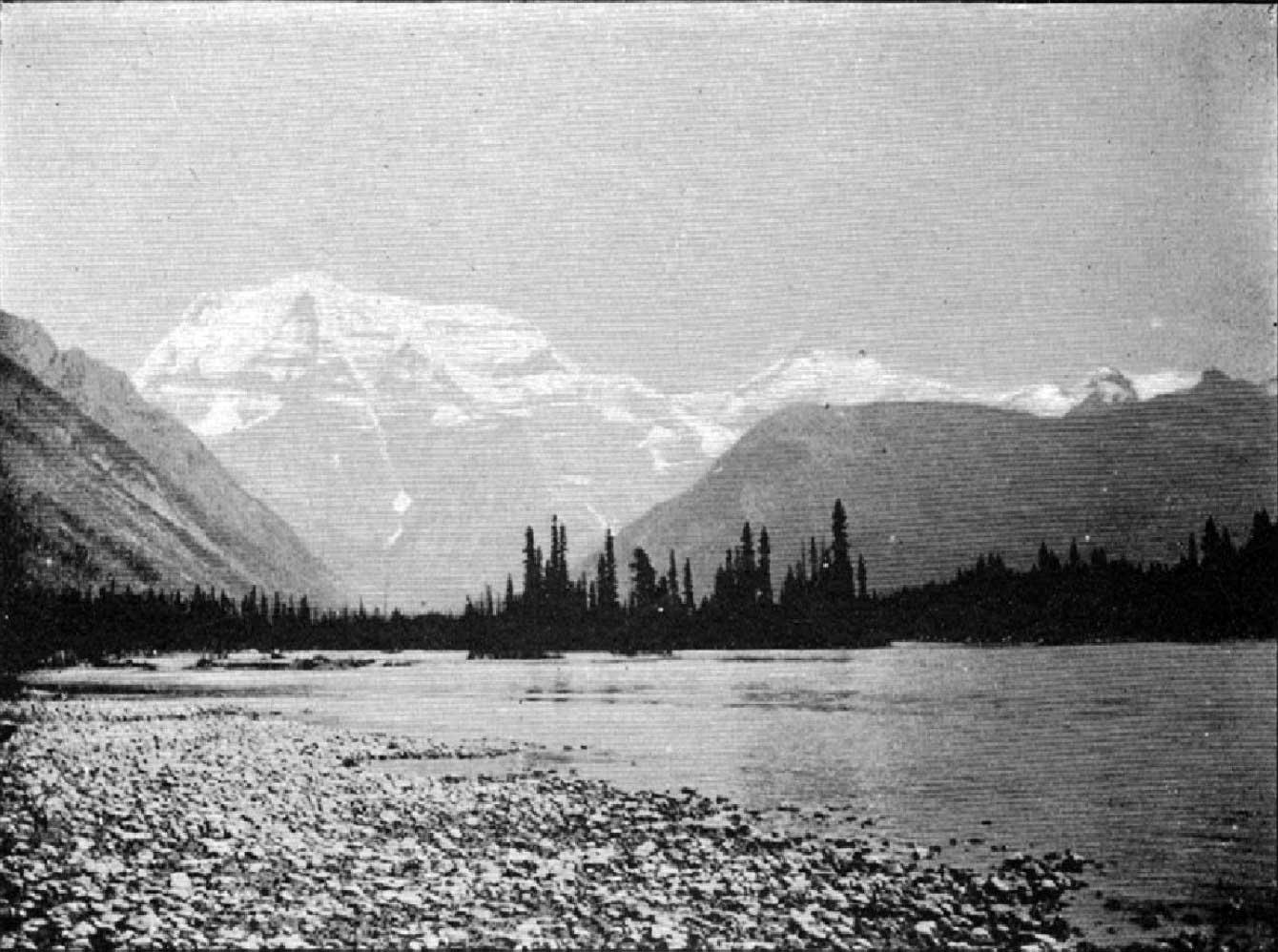

Mt. Robson, Grand Fork, Fraser River.

Photo: James McEvoy, 1898

Report on the geology and natural resources of the country traversed by the Yellowhead Pass

According to George Mercer Dawson, who did geological work in the area from 1887 to 1890, this highest peak in the Canadian Rocky Mountains was called Yuh-hai-has-kun, “mountain of the spiral road,” by the Secwépemc (Shuswap) people of the North Thompson River from the appearance of a track running around the mountain. It was already known as Robson’s Peak by 1863 when Milton and Cheadle passed by. It may have been referred to as Mount Robinson as early as 1827, according to a now lost copy of fur trader George McDougall’s journal. In 1937, historian A. G. Harvey reviewed seven theories about the mountain’s namesake, and concluded that the source was a mystery.

The most probable of the contending theories about Mount Robson’s name, dating from the fur trade era, is that it was named after Colin Robertson [1783–1842], a Hudson’s Bay Company officer. In 1820 Robertson was charge of the Hudson’s Bay Company post of Fort St. Mary’s on the Peace River across from the mouth of the Heart River. Robertson sent a company of Iroquois fur hunters across the Rockies to the area around Tête Jaune Cache. This party, with Ignace Giasson in command and Pierre Bostonais called “Tête Jaune” [d. 1827] as guide, must have passed close to Mount Robson and may have named it.

Robertson started as a clerk in the North West Company in 1804. He was dismissed in 1809, and entered the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service in 1814. He took charge of a party of colonists sent to the Red River Settlement by Lord Selkirk in 1815, and in 1816 captured and destroyed Fort Gibraltar, a North West Company post. Arrested by North West Company officers in 1819, he escaped and was in England during the negotiations for the union of the two companies. Robertson returned to Hudson’s Bay in 1821. He served at Norway House until 1824, at Fort Churchill until 1830, and at Swan River until 1832. After his retirement in 1840, he was elected to the House of Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1841.

Historian Brian Patton in a personal correspondence reports that in the manuscripts of Walter Butler Cheadle [1835–1910] at the Public Archives of Canada, there is a hand-written note on the crossing of the Rockies, in which Cheadle states: “this lofty peak, called I believe Robson’s peak [by] Hudson’s Bay Coy voyageurs was an almost perfect cone capped with snow…”

The mountain was not named after British Columbia premier John Robson, for he did not become premier until 1889. Nor, according to a letter from Ebenezer Robson [1835-1911] to George Kinney, was it named after himself, a Wesleyan Methodist missionary and explorer who left Toronto on December 31, 1858, along with Edward White and Arthur Browning, to break trail into this “then unknown country.”

The earliest description of the mountain is found in the journal of John M. Sellar, one of the Overland party of gold seekers bound for the Cariboo, who passed the peak on August 26, 1862. “At 4 p.m.,” Sellar wrote, “we passed Snow or Cloud Cap Mountain which is the highest and finest on the whole Leather Pass. It is 9000 feet above the level of the valley at its base, and the guide told us that out of twenty-nine times that he had passed it he had only seen the top once before.”

T.C. Young of Jasper, who worked on the construction of the Canadian Northern Railway line in 1915, said, “At that time several lodges of Shuswaps Indians were living at Tête Jaune Cache. One Indian who could speak English very well — he was a man about sixty years of age — said that as long as he could remember Mount Robson was known as Robson’s Peak, but he did not have any knowledge of the original naming.” The Indian’s father said that when he was young man, a white man named Robson was killed shoeing a horse “at the junction of Grand and Fraser Rivers, or on the old site of Tête Jaune Cache.” (The Grand River is now called Robson River.) Harvey, who relates this story, doubts whether there would have been a blacksmith at Tête Jaune Cache as long ago as the story told to Mr. Young would imply, 1850 or earlier.

Other persons who have interviewed natives on the subject have obtained different stories. Dr James Monroe Thorington, of Philadelphia, an eminent mountaineer, wrote, “The Cree Indians call Robson simply, ‘The Big Mountain,’ but this seems to be a modernism; old men, with whom I have talked, say that their tribe never had a special name for the peak .”

Arthur Coleman’s influence was largely responsible for blocking an attempt, sometime before 1938, arising from “a mistaken idea of patriotism, to rob Mount Robson of the name it has so long held.” What was the proposed change?