Flows SW into Canoe River

52.7 N 119.05 W — Map 83D/11 — Google — GeoHack

Name officially adopted in 1974

Official in BC – Canada

Pre-emptor’s map Tête Jaune 3H 1919

Origin of the name unknown.

Origin of the name unknown.

Among depots that were left vacant on the abandoned Grand Trunk Pacific Railway grade in 1917. Yellowhead burned down about 1918.

Bohi lists “Summit” and “Yelsum” as previous names for this station.

The Yellowhead Pass. Sir Sandford Fleming, based on an expedition in 1872

Alpine Club of Canada

On the Yellowhead Pass.

Photo: Mary Schaffer, 1908

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

Sunset on the Yellow Head Pass.

Photo: Dr. J. Norman Collie, 1910

Alpine Journal 1912

Monument placed at summit of Yellowhead Pass.

Photo: A. 0. Wheeler, 1911

Canadian Alpine Journal 1912

Appears as “Yellow Head Pass” on Hanington’s map.

“Tête Jaune Cache is some fifty miles down on the west side from the summit of Yellowhead Pass, not far from the junction of the North or Grand fork with the southerly branch of Fraser River. It was so named from the fact that an Iroquois trapper known as “Tête Jaune” or “Yellow Head,” made this cache the receptacle for his catch of fur. He seems to have been a man of some celebrity in the neighborhood for, presumably, the pass has been named after him.”

— Arthur Wheeler

“Tête Jaune” was the nickname of Pierre Bostonais [d. 1827], a guide of Iroquois extraction who worked for the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company . In 1825, he guided the first party recorded to cross this pass. From 1826 until the 1850s, the pass was occasionally used by the Hudson’s Bay Company to transport leather from the Saskatchewan District to New Caledonia. Despite its low elevation — at 1,131 metres second only to the Monkman Pass in the Canadian Rockies — and its mildly inclined approaches, it was used only sporadically during the fur trade. The route over the Yellowhead Pass stretched, without intervening posts, for more than 600 km between Jasper House, on the Athabasca River, to Fort George, on the Fraser. “The lengthy and uninterrupted isolation imposed on the brigades along the route, the unreliable navigability of the Athabasca and Fraser rivers, and the unpredictable weather of the usual mid-autumn journey presented problems,” according to historian David Smythe.

“It was also used to some extent by the Rocky Mountain Indians of the Shuswap tribe on the journey from Kamloops via Thompson River to Athabasca River at Jasper House, where, presumably, they carried on trade with the fur company,” according to Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945], who surveyed the pass in 1917 for the commission appointed to delimit the boundary between the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia.

The fur traders who used this pass in the first half of the nineteenth century never called it, or any other mountain pass, a pass. They called it a portage. Infrequently called the New Caledonia portage in the letters and journals of the period, the Yellowhead Pass was almost exclusively referred to as the route or portage via Tête Jaune Cache. On a few occasions in the 1820s, the officer in charge of New Caledonia referred to the route as “the Leather track,” encompassing the entire distance between Fort George and Jasper House. After 1860, the pass was also briefly known as the Cowdung Pass, after an early name of Yellowhead Lake. It was also referred to at various times as Leatherhead Pass, Jasper and Jasper House Pass, Tête Jaune and Tête Jaune Cache Pass, Myette Pass, and even the Rocky Mountain Pass. The actual name “Yellowhead” appears to have first been used on the Arrowsmith 1859 map.

Sir Sandford Fleming crossed the pass in 1872, reconnoitering a route for the Canadian Pacific Railway:

A few minutes afterwards the sound of a rivulet running in the opposite direction over a red pebbly bottom was heard. Thus we left the Myette flowing to the Arctic ocean, and now came upon this, the source of the Fraser, hurrying to the Pacific. At the summit Moberly welcomed us into British Columbia, for we were at length out of “No man’s land,” and had entered the western province of our Dominion [B.C. became a Canadian province in 1871]. Round the rivulet running west the party gathered and drank from its waters to the Queen and the Dominion. Where had been little or no frost near the summit, and flowers were in bloom that we had seen a month ago farther east. Before encamping for the night we continued our journey some twenty-six miles farther into British Columbia, well satisfied that no incline could be more gentle than the trail we had followed to the Pacific slope through the Yellow Head pass.

“It was originally selected as the route of the Canadian Pacific Railway but was later abandoned,” Wheeler noted. “Now it is crossed by two other transcontinental lines of the Canadian National Railways.”

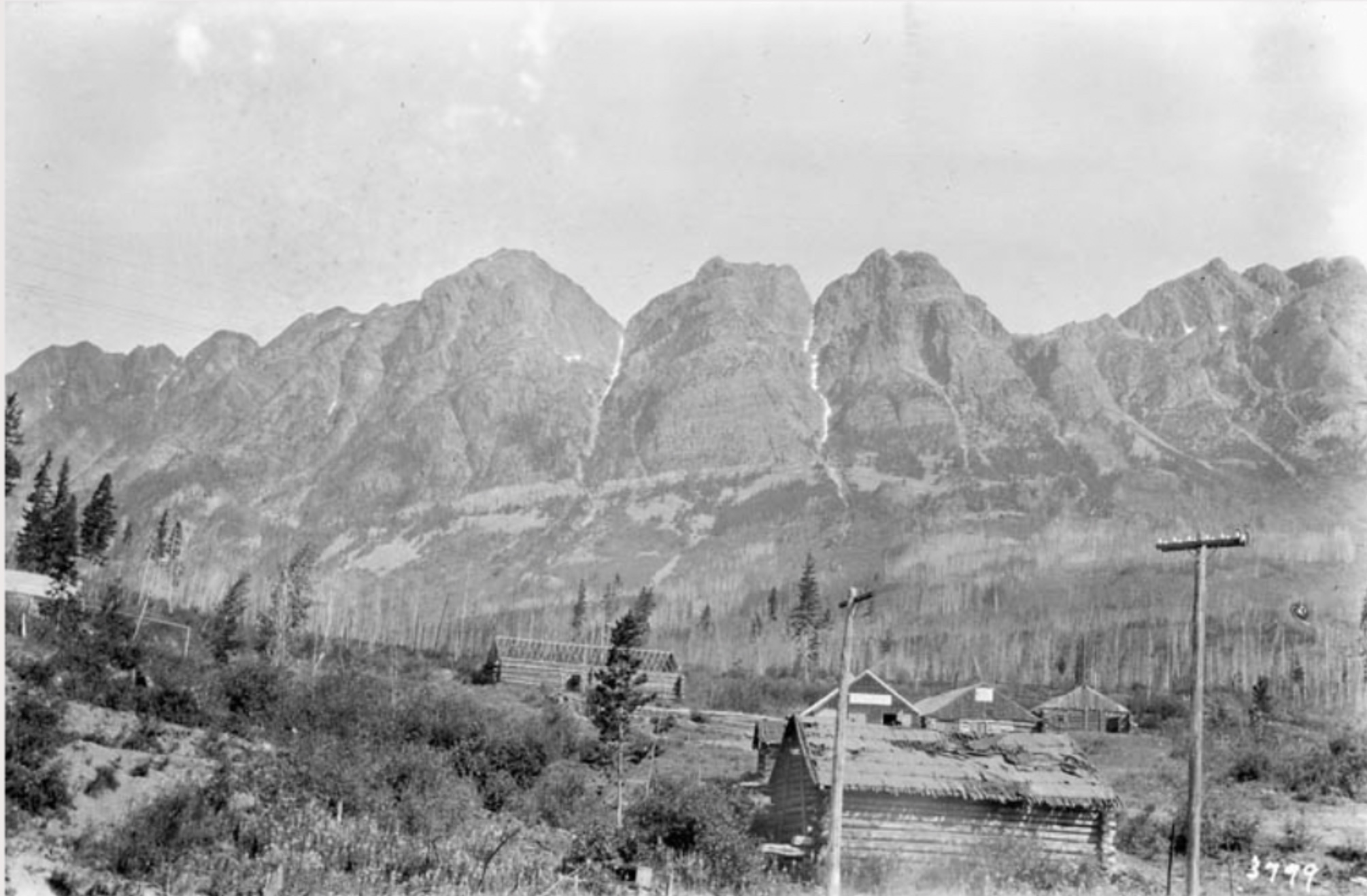

Seven Sisters Yellowhead Lake, Lucerne, B.C.

William James Topley, 1914

Library and Archives Canada

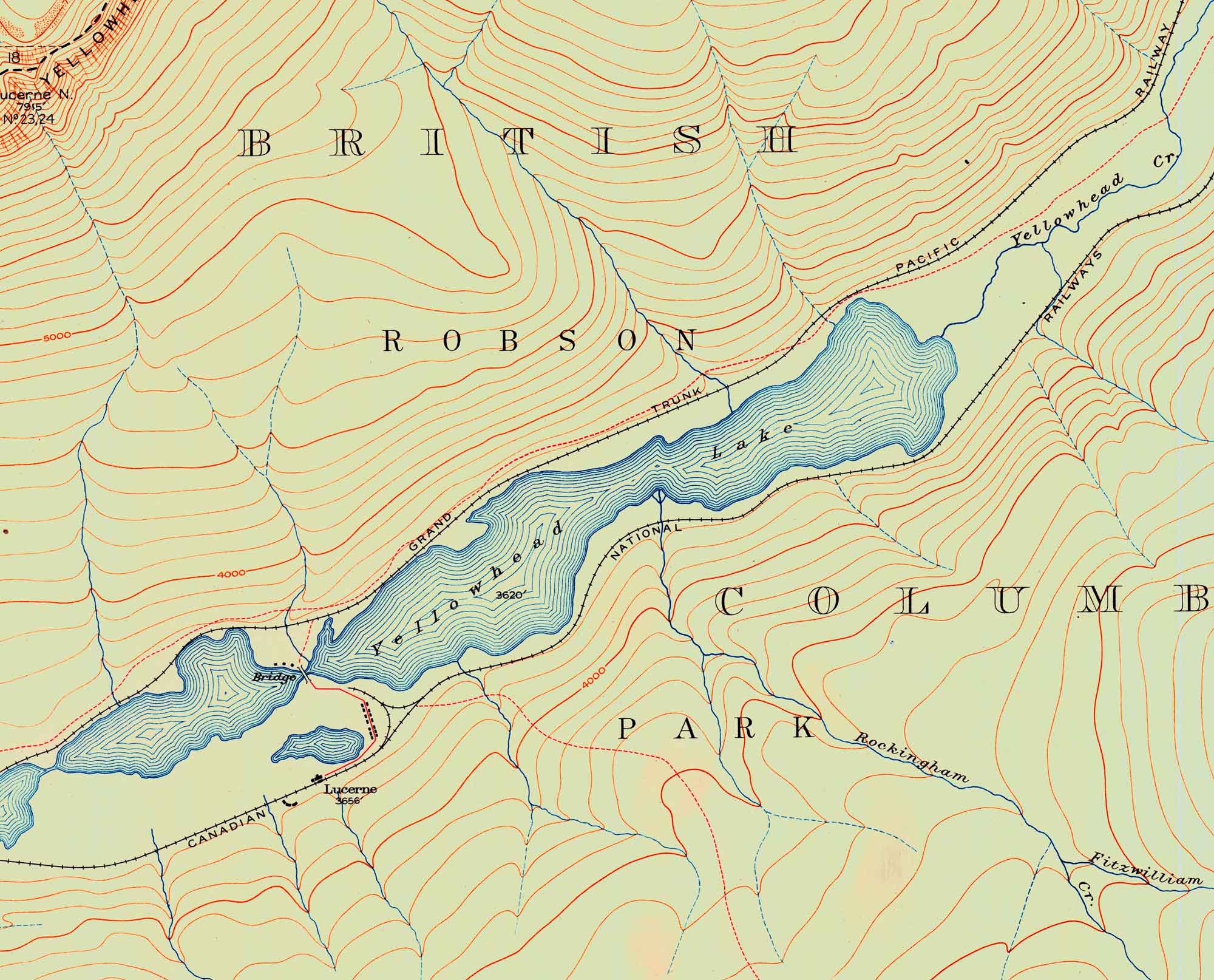

Yellowhead Lake. Surveyed in 1917. Boundary between Alberta and British Columbia. Detail.

Internet Archive

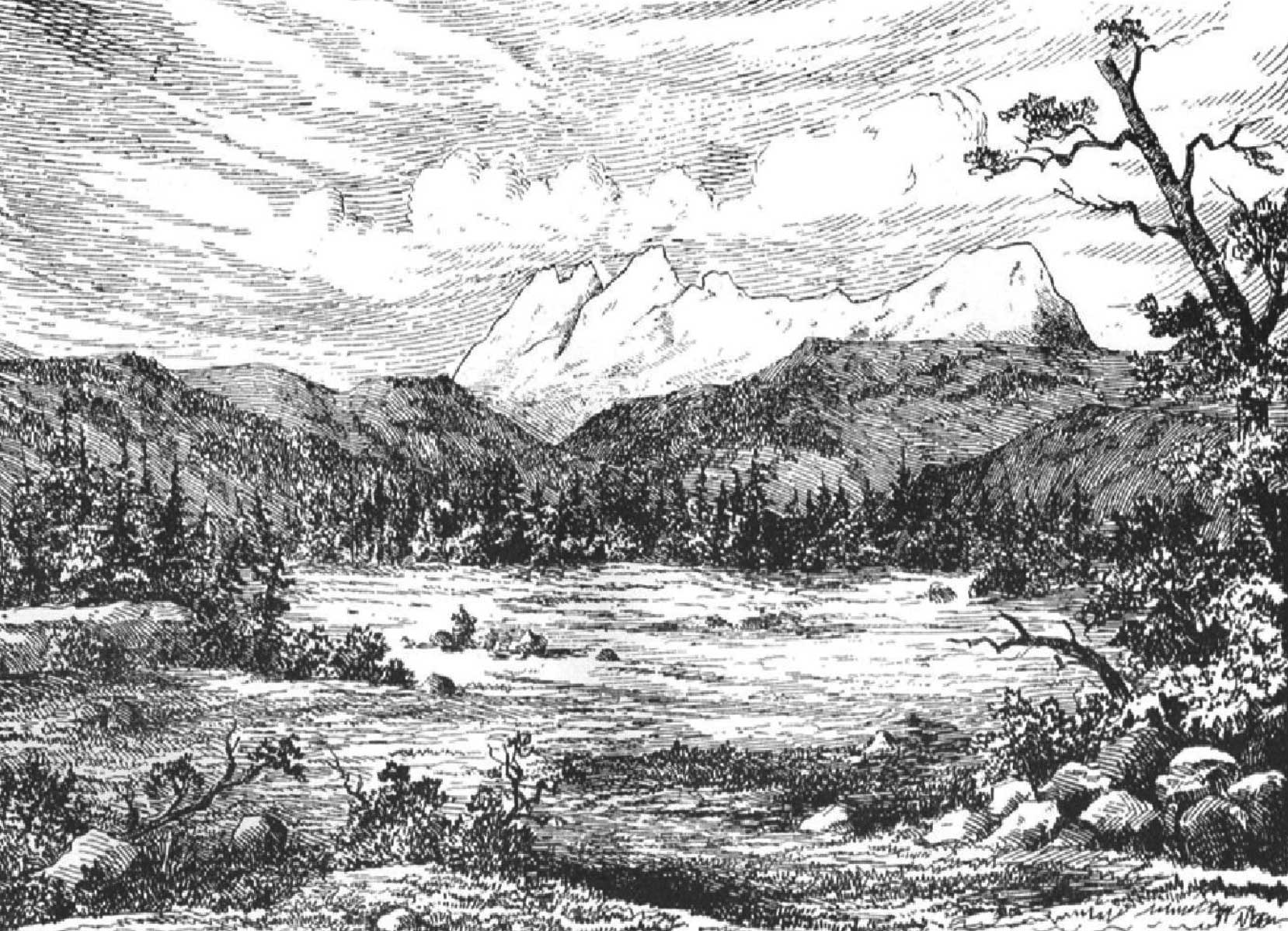

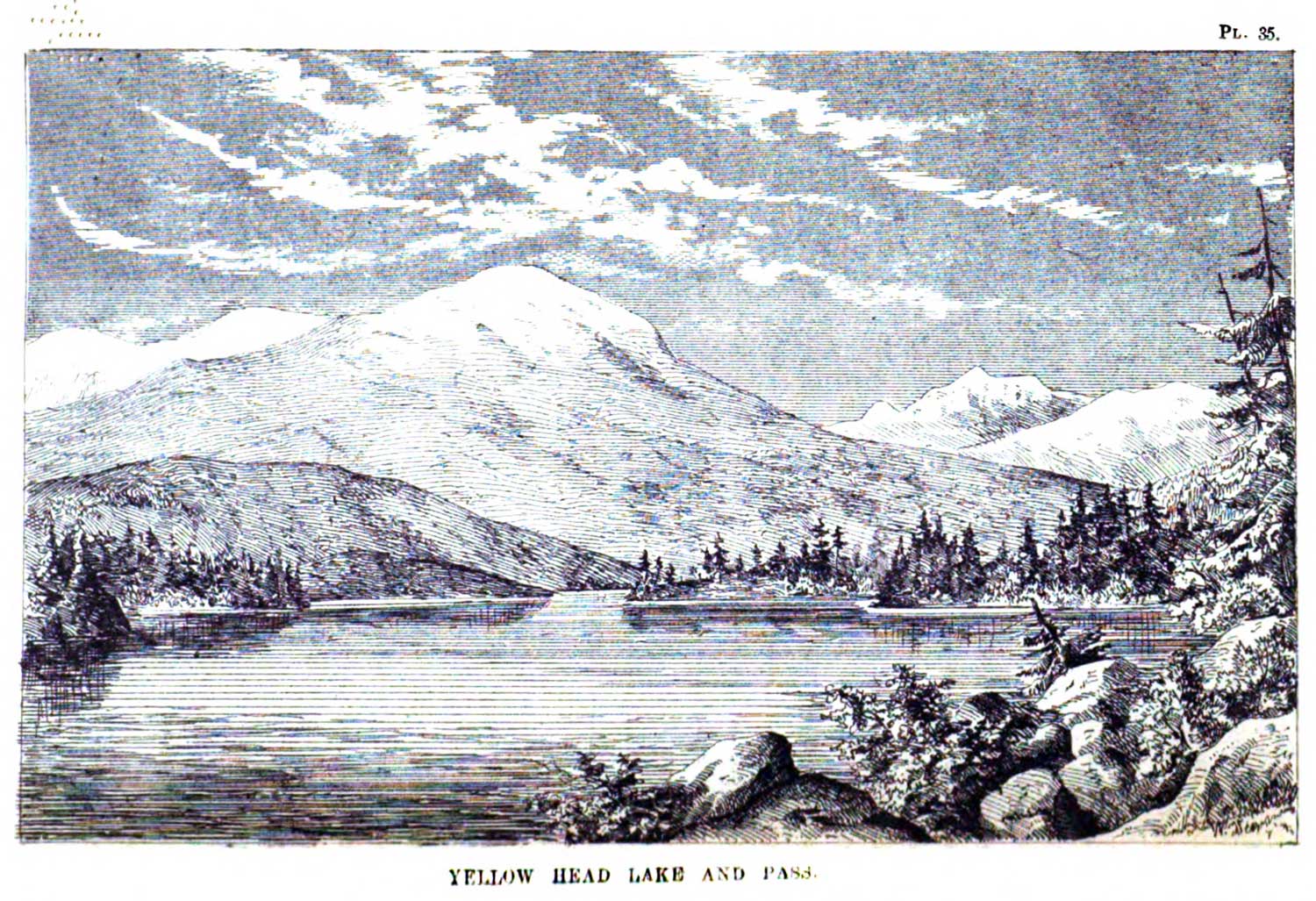

Yellow Head Lake and Pass. George Monro Grant, plate 35

Ocean to Ocean: Sandford Fleming’s Expedition through Canada in 1872

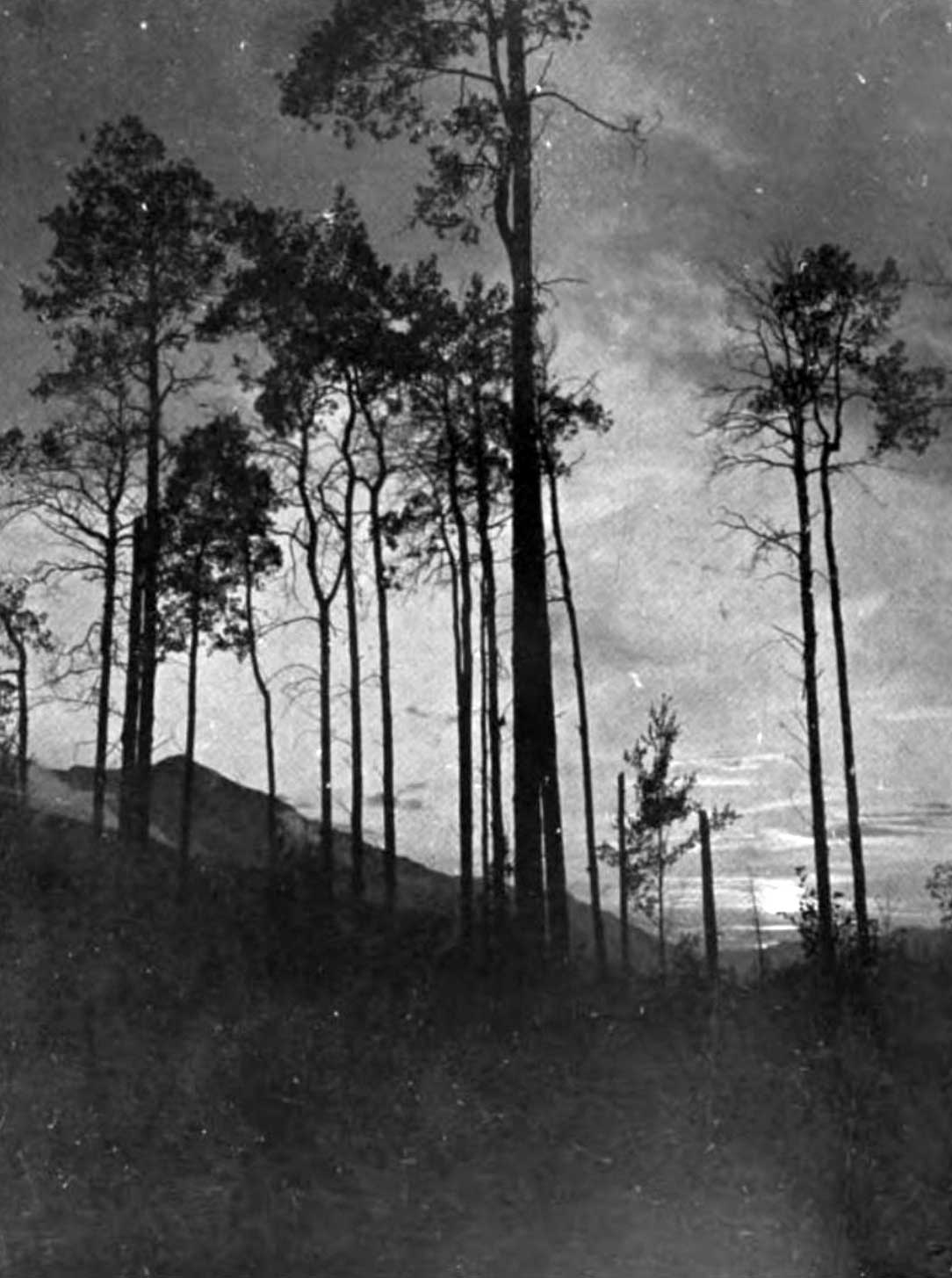

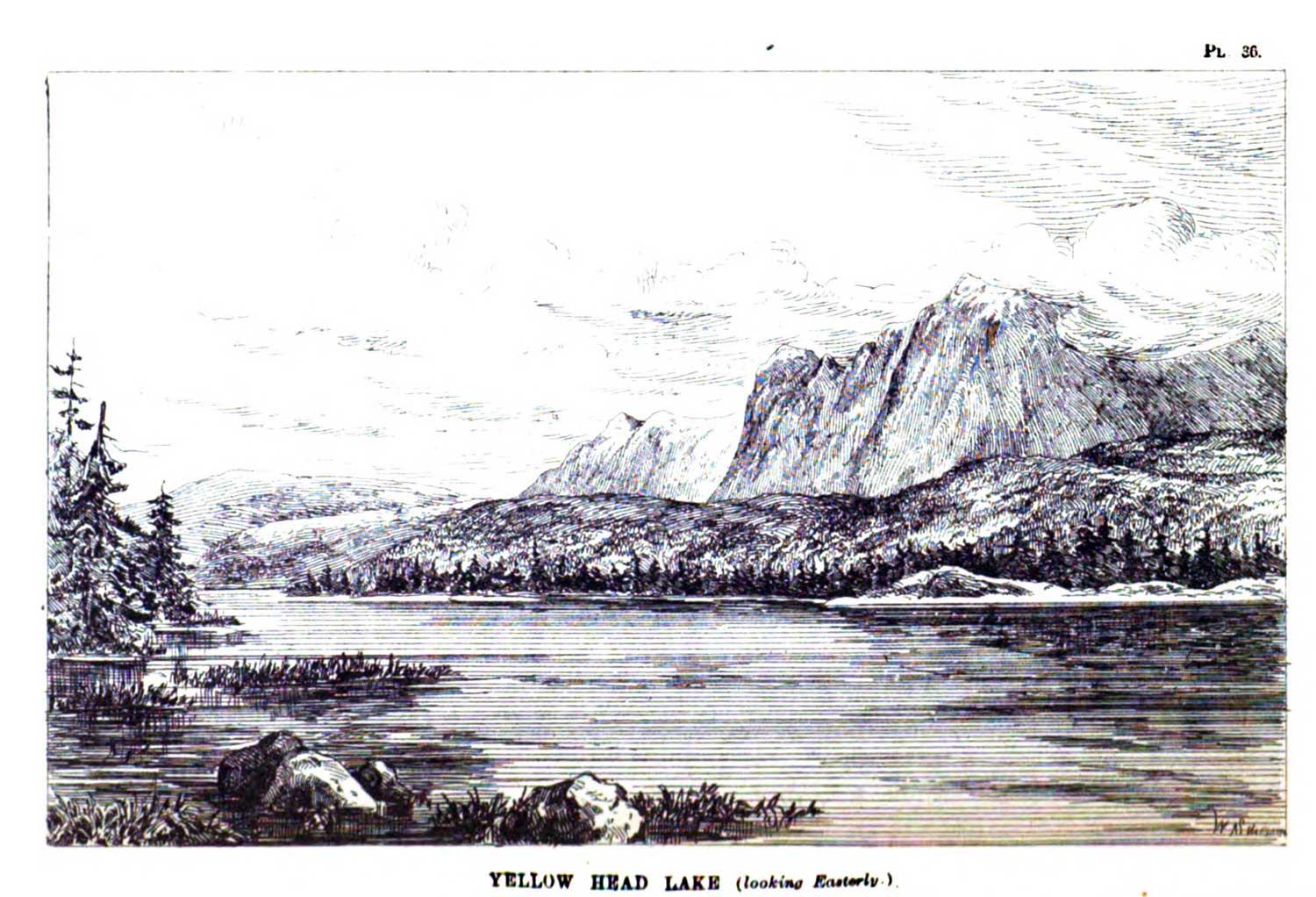

Yellow Head Lake (looking Easterly). George Monro Grant, plate 36

Ocean to Ocean: Sandford Fleming’s Expedition through Canada in 1872

Yellowhead Lake looking east.

Photo: Mary Schäffer, 1908

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

This lake near the Yellowhead Pass has been known by several names. In 1824, Hudson’s Bay Company governor George Simpson [1792–1860], heading for the Athabasca Pass, noted, “the track for Cranberry Lake takes a Northerly direction by Cow Dung River.” The Cow Dung River was the Miette River and Simpson’s Cranberry Lake may have been our Yellowhead Lake. In 1862, when the Overlander gold seekers crossed Yellowhead Pass (which they called Leather Pass) they camped on Cow Dung Lake. A year later, the lake was known to Milton and Cheadle as Buffalo Dung Lake. In 1872 George Monro Grant [1835–1902] suggested its present name, recalling the namesake of the pass.

“It is a very charming litle sheet of water,” wrote Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945], “four miles long, with a greatest width of half a mile. There are several narrows, and the irregularities of its form are by no means the least part of its charm. For the most part it is surrounded by green forest and is distinctly one of the most beautiful lakes in the district. In colour the waters are a creamy sap green.”

On Arrowsmith’s 1859 map the two sections of Yellowhead Lake are called “Moose L.” and “Cow dung L.” On the map present-day Moose Lake is called “L. d’Original,” a misspelling of the French Canadian “Lac Orignal.”

BC Parks has a bathymetric map of Yellowhead Lake.

Association with Yellowhead Lake.

In 1884, Yates’s family moved to California, and Yates attended high school in San Diego. Around 1906 he homesteaded on Hobo Ranch, west of Lac Ste. Anne (about 45 miles west of Edmonton). With his brother Bill, he packed supplies for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railwaysurveyors, and in 1907 he contracted to carry the mail to railroad construction camps between Edmonton and Tête Jaune Cache.

While carrying the mail past the base of Mount Robson in September 1907, Yates ran into Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939] and his mountaineering party. Returning from their unsuccessful attempt to climb Robson, Coleman’s party met Yates again at Big Eddy, and Arthur Coleman accompanied the mail-carrier to Edmonton. “Before bidding goodbye to Yates, the hustler, born in England and brought up in California, I sounded him as to another expedition the following summer,” Coleman wrote, “and found him willing to arrange for horses if I wanted to go.”

In 1908 Coleman’s party regrouped at the Hobo Ranch and, guided by Yates with the assistance of Adolphus Moberly, approached Mount Robson by way of the Moose River. On September 5 the climbers, including Yates, who carried an alpenstock he had made out of a pole and a heavy wire nail, reached the 10,000 foot level, but had to turn back because of the lateness of the day and Yates’s frozen feet. The group made two more attempts, and group member George R. B. Kinney [1872–1961] made a solo climb, but they left Robson a virgin peak, arranging with Yates to try again in August of 1909.

In May of 1909, Kinney heard that “a party of foreigners” were planing to assault Mount Robson that summer. He sent a frantic wire to Yates and hurried from his home in Victoria to Edmonton. Awaiting him was a letter from Yates, explaining that it would be madness to start for the mountain so early in the year, especially since spring had been very late and the snowfall exceptionally heavy. Kinney hit the trail alone, teamed up with Donald “Curly” Phillips [1884–1938] near Jasper, and went on to climb Mount Robson, a feat which was later disputed. Returning to Edmonton, Kinney and Phillips met the dreaded “party of foreigners:” Arnold Louis Mumm [1859–1927], Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery [1873–1955], Geoffrey Hastings, and mountain guide Moritz Inderbinen [1856–1926], under the care of John Yates. The party was not successful at Mount Robson.

In 1910, Yates guided Mumm and Collie to the Mount Robson area, where they “discovered a splendid snow mountain that Yates named Mt. Bess,” after Elizabeth Gunn of Lac Ste. Anne, on whom Yates had a crush. In 1911, Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945] in the vicinity of Calumet Creek, noticed an “old blazed track known as the Yates trail, because it was made by a packer of that name…. The Yates trail comes out in an open at the highest point. It well might be called ‘Exclamation Point.’ Looking south in the V of the valley, Mt. Resplendent stands a great white cone, clad from head to foot in eternal snows. Below, the the left, Yates Torrent issues from the forefoot of Coleman Glacier, a splendid icefall, the main northern outflow of Reef Névé.”

“Yates Torrent” did not become an official name; the stream issuing from the Coleman Glacier is an unnamed tributary of the upper Smoky River.

Yates retired from outfitting and moved back to California, ca.1920.

Earl Francis Woodley [1892–?] was postmaster at Red Pass Junction from 1923 to 1946. Earl and his wife Edna (1899-1971) ran the Red Pass general store and hotel from 1923 until 1944. Earl’s father, about 70 years old in 1944, was bartender in the pub. One of the Woodley boys married a Hinkelman girl and lived in McBride.

Called “Flat Heart River” by David Thompson [1770–1857] in 1811, who descended it after crossing the Athabasca Pass.

Our residence was near the junction of two Rivers from the Mountains with the Columbia: the upper Stream which forms the defile by which we came to the Columbia, I named the Flat Heart, from the Men being dispirited ; it had nothing particular. The other was the Canoe River ; which ran through a bold rude valley, of a steady descent, which gave to this River a very rapid descent without any falls….

In his edition of the journal of Edward Ermatinger [1797–1876], who crossed the Athabasca Pass with a fur brigade in 1827, James White notes that “the Wood river was apparently so named after the dense forest traversed by the portage road up its valley.”

Origin of the name unknown.