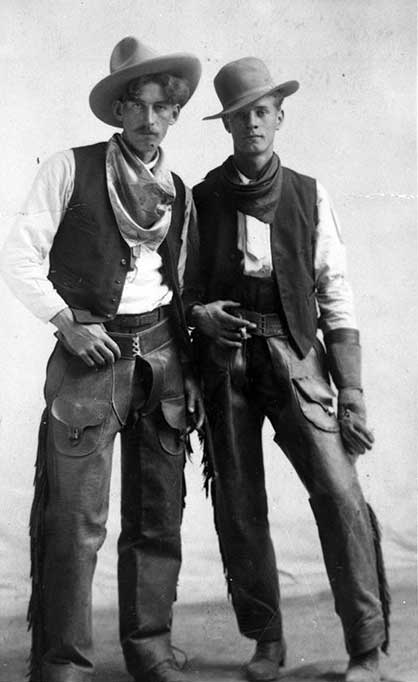

Stanley Joseph “Windy” Carr [1890–1983] was born in Leyton, Essex, England, to Frederick Joseph and Fanny Carr. In 1907 Carr came to Canada, “pursuing a dream to be a cowboy.” In 1910, after working on cattle ranches in the Calgary area, he became a guide for Brewster Brothers at Lake Louise (1). He joined the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force in 1916, suffered a shrapnel wound in the foot while serving in France in the cyclist battalion, and was demobilized in 1919 with pay of $116, including $15 separation allowance and back pay at $1.10 per day (equivalent to about $20 today) (2).

With two other returned veterans, he started an outfitting business at Banff. In 1921 he married Scottish-born Jessie Clark [b. 1895], who had come to Calgary with her family in 1910. After a year in Calgary, the Carrs moved to Los Angeles. In 1926, the “call of the Rockies” brought them back to Canada. After working a year for the Hargreaves at Mount Robson Ranch, Carr bought property at Tête Jaune Cache and built a home and guest ranch, the Half Diamond M Ranch. He became a popular outfitter and guide for mountaineering expeditions in the area (3, 4).

Carr served as justice of the peace, postmaster (1937–1953) (5), stipendiary magistrate, juvenile court judge, coroner, school trustee, and honorary fire warden, and was a sergeant in the Pacific Coast Militia during World War II. He was a lifetime member of the Masonic Lodge at Cochrane, Alberta, and a long time member of the McBride Royal Canadian Legion. He worked for years to get the Yellowhead Highway completed. Carr was known as “Windy” because of the stories he delighted to tell. He died in Victoria. Jessie (“Jay”) Carr celebrated her 90th birthday in 1985, at Mount Robson.

Carr Road was originally part of the old wagon road from McBride to Valemount. When a new bridge was built across the Fraser River at Tête Jaune Cache, the wagon-road bridge was blasted out.

References:

- 1. Stewart, Maryalice Harvey. Brewster family and Stanley Carr research. 1967. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

- 2. First World War Personnel Records, Library and Archives Canada. Carr, Stanley

- 3. Zillmer, Raymond T. [1887–1960]. “The first crossing of the Cariboo Range.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 31 (1948):26–37

- 4. Wexler, Arnold [1918–1997]. “Ascents in the Cariboo Mountains.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 27 (1950):41-50

- 5. Post Offices and Postmasters: 1851 – 1981 (1851–1981). Library and Archives Canada