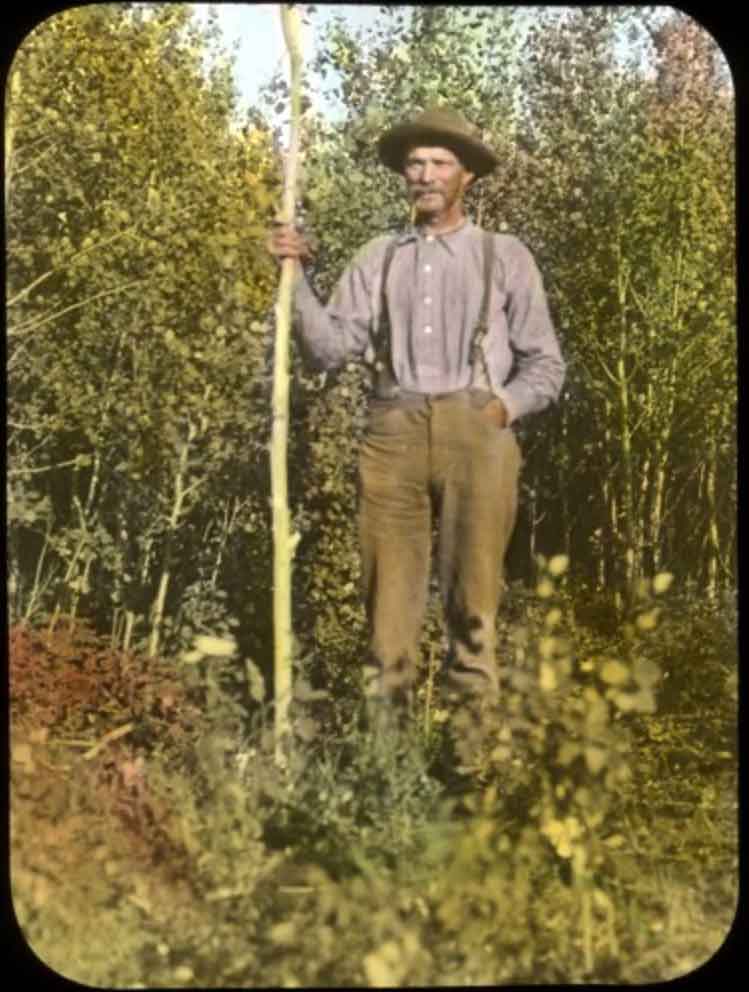

Lewis John Swift [1854–1949] appears to have been first white man to settle in what is now Jasper National Park.

Two miles and a quarter below Maligne River, on the west side of the Athabasca, a piece of land has been taken up by Mr. Swift, who has demonstrated that the country is capable of producing wheat, potatoes, and various kinds of vegetables. On September 2 he had harvested a crop of two kinds of wheat and his potatoes were of good size and quality. A great part of the Athabasca valley would make good farming land, the higher ground, however, would require irrigation.

— McEvoy 1900

Somewhere in there we passed a place with a board that said, “Athabasca House,” and another was, “Henry House.” All we could see of that was a kind of square where the logs had been rotted or burnt, but one of them showed the remains of an old fireplace made out of clay. Then we travelled about eight or ten miles and came to Swift Creek. There was an old squaw man there name of Swift. He had married an Indian woman and they had four or five children and a ranch — a little farm there.

— McDonald 1907

List of photographs:

#91 – Swimming the Athabaska [1908]

#92 – [(Lewis Swift)? 1908]

#93 – The Swift Family [Mrs. Lewis Swift and four children 1908]

#94 – [Mrs. Lewis Swift and four children in front of their home, 1908]

#95 – [One of the Swift children, 1908]

#96 – [Mrs. Lewis Swift and four children, 1908]

#97 – Swift’s mill for flour [1911] / [Byron Harmon]

#98 – Cows at Swifts’ [1908]

#99 – Looking toward Yellowhead Pass Athabaska River – Miette Valley 1908] (p.302)

— Schäffer 1907

But those nineteen days to the Yellowhead were crowded full of unique experiences as well as hard labor. We purchased provisions at the Big Eddy, Prairie Creek, Moberlies and Swifts.

— Kinney M200 1909

After packing up we went about a mile to Mr. Swift’s tiny ranch and farm. It is customary to stop over a day at Swift’s, as this is the last of civilization. But alas for Swift! his big day is now past; for the coming of the railroad brings a change over all the old ways and good old days of the pack trail.… During the afternoon while stayed in camp and did some cooking, Mr. Kinney went out and picked enough wild strawberries for supper. The next morning, after getting a few supplies from Swift and a couple of pecks of potatoes, we started westward and camped early at Caledonia Creek, the first tributary of the Miette River.

— Kinney and Phillips 1910

Planned another attempt.… Set out from Edmonton on August 1, 1908, with John Yates as packer… engaged Adolphus Moberly at Swifts… our mapping included two beautiful lakes, Adolph, on the Smokey River side, and Berg Lake, on the Grand Forks side.

— Coleman 1910

Chapter 31. Swift and his neighbors. Our supplies were nearly done when we once more touched the Athabasca River, and we went down stream a few miles to Swift’s ranch, of which we had heard much from all travellers to and from Tete Jaune Cache. Swift is a most interesting character, a white man of some energy and resource who married a woman of the country, an Iroquois half-breed, many years ago, and had now a brood of wholesome -looking children playing about his log house. He had fenced and ploughed some fields, from which wheat and oats and barley had just been harvested, and had built a watermill on the stream that irrigated his farm to grind his wheat into flour, somewhat brown in colour, but making good bread ; so that, except for sugar, tea, and tobacco, he was as nearly independent as a man can be.He reached this valley in 1894, the year when we had mistaken the Miette for Whirlpool River, had seen our tracks and wondered at them, just as we had pondered over the big hoof -prints of his horses. It was strange that two parties of white men, one from Morley, the other from Edmonton, then only a fur -trading post, should so nearly have met at the sources of the Athabasca.

— Coleman 1911

Lewis John Swift was born February 20, 1854, in Cleveland, Ohio. He set out for the west as a young man, and worked in many of the early mining camps in the Denver area, spent some time in the Black Hills, and for a spell drove the stage from Bismark to Deadwood. After years in the mountain states, he turned up in the embryo Calgary of 1888 and soon moved to the less-crowded outpost village of Edmonton. There or at Lac Ste. Anne he met many of the natives from the Jasper area and in 1890 travelled west with the Moberlys, until he was once more in the mountains. But he was still on the move and before long passed west through the Yellowhead Pass to emerge in due course at Mission Creek in the Okanagan, where he appears to have spent the next two years. Swift was drawn to the Jasper valley and in 1893, bringing a six-inch grindstone and a supply of trade goods, he returned. For two years he lived in the only building that was left of old Jasper House which had been abandoned about ten years earlier. He studied thevalley for two years before he build a new home in the shadow of the Palisades on a piece of land which he thought would make a good divisional pount whenever the rumored second transcontinental railway would be built. He cultivated a little patch of soil and in due course, by irrigating some of it from the stream which flowed past his door, he grew potatoes, wheat for flour, and oats for his horses. He continued trading in a small way and on one trip to Edmonton brought out some cattle and loaded his pack horses with a few domestic chickens. In 1897, near Edmonton, he married the mixed-blood Suzette Chalifoux. Washburn met Swift. Before the coming of the railroad, all travellers passed his doorway, many in desparate need of the provisions which only he could supply. By 1909, Swift was an institution, and would remain one until his death forty years later.

— MacGregor 1974

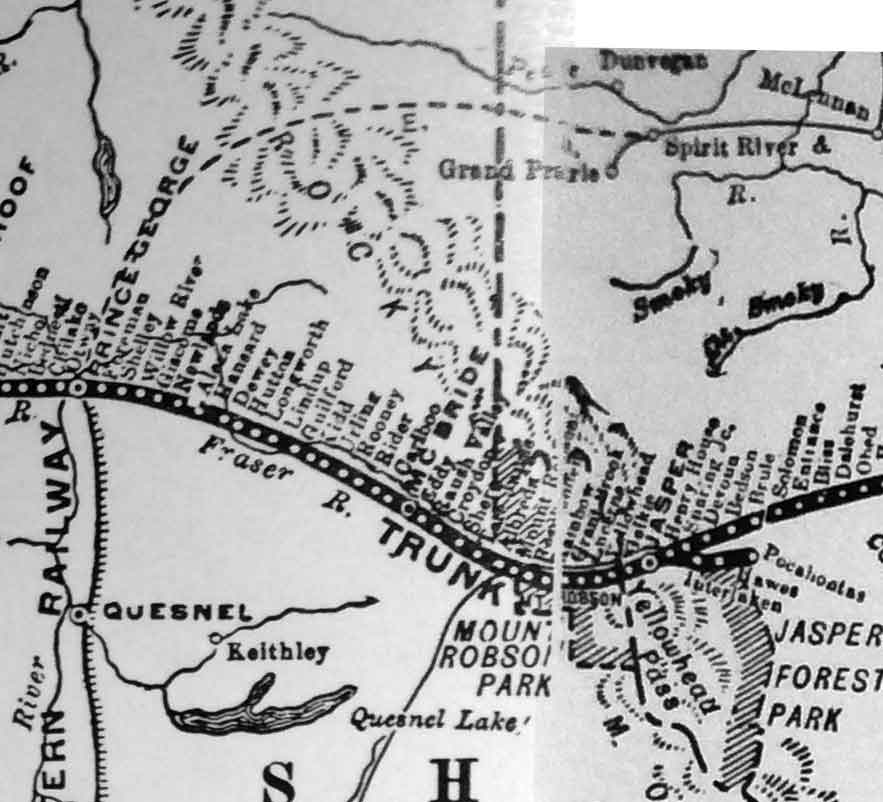

![Rand McNally railway map [detail], 1925](/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cnr-map-1925.jpg)