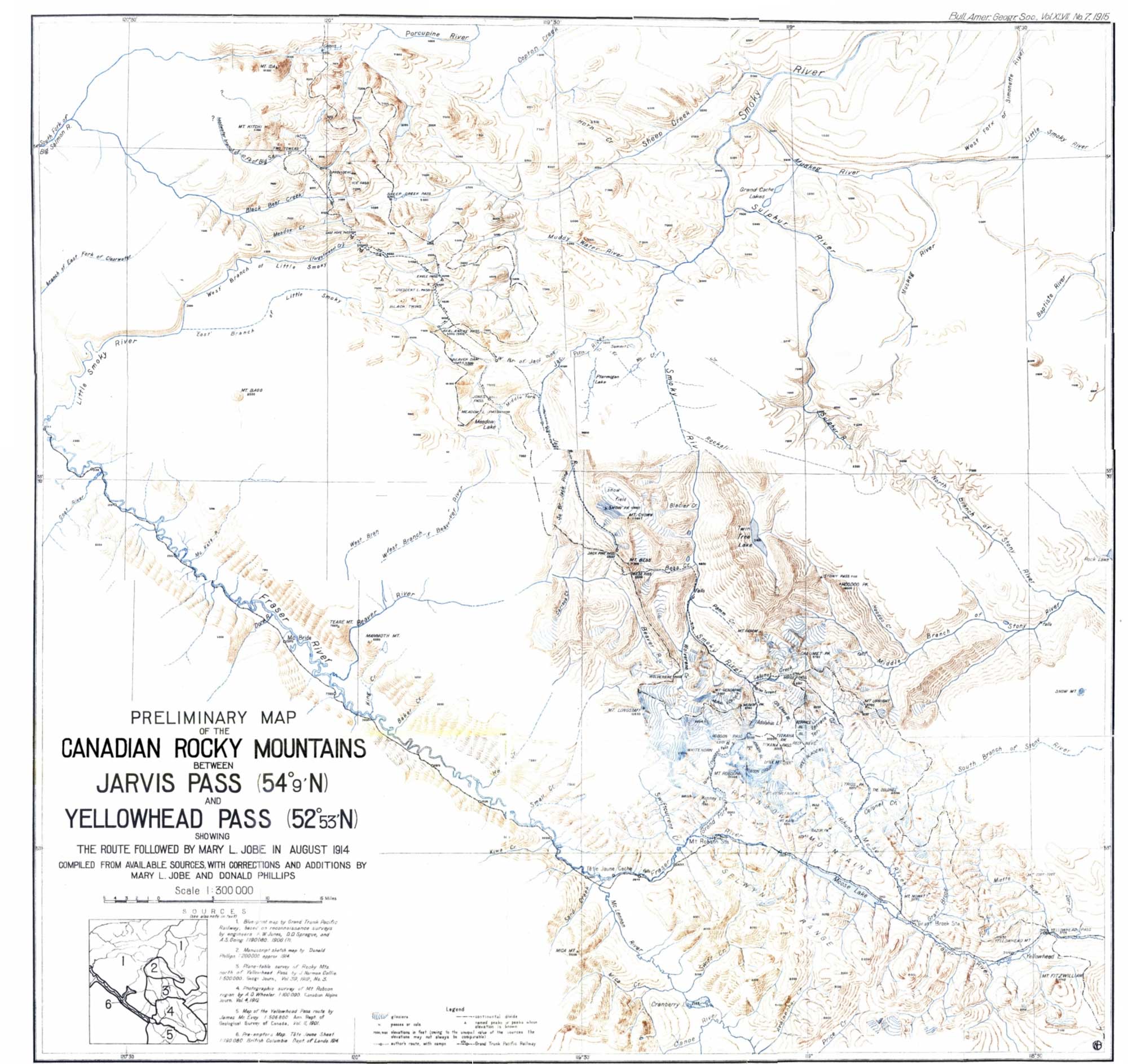

Preliminary Map of the Canadian Rocky Mountains between Jarvis Pass (54°9’ N) and Yellowhead Pass (52°53’ N). Showing the route followed by Mary L. Jobe in August 1914. Compiled from available sources, with corrections and additions by Mary L. Jobe and Donald Phillips

Mary Lenore Jobe Akeley [1878–1966] of Connecticut, Margaret Springate of Winnipeg, and guide Donald “Curly” Phillips [1884–1938] of Jasper made an expedition into the Canadian Rockies of Alberta and British Columbia, northwest of Mount Robson.

The map in the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society (Volume 47, No. 7, 1915) is accompanied by the following lengthy note:

To accompany her article Miss Joe had originally prepared a sketch map, based on her and Donald Phillips’s observations, which, while showing remarkably well the essential features of the country, did not partake of the nature of an instrumental survey. Subsequently an unpublished blue-print map of the Grand Trunk Pacifie Railway (1a in appended list of maps) came to her knowledge, which showed in contours the topography of the whole mountain region between Jarvis Pass and the transverse courses of the Jack Pine and Smoky Rivers and its relation to the Fraser valley. Recognizing that this was a much more satisfactory representation, being based on an instrumental survey, it was decided to use it, together with all other available sources, in the compilation of a new map. As the blue-print map contained no geographic coordinates, it was necessary to supply them. This was done by drawing the parallel of 53° and the meridian of 119° in their proper positions as deduced from the known astronomic position of the township and range lines shown on the Yellowhead sheet of the Sectional Map of Western Canada (7) and from them expanding the coordinate net over the rest of the map. The resulting position of Jarvis Pass was 53°59′. and of the head of the larger lake at the head of the right source-stream of the Porcupine, 53°51′. The corresponding positions on the two most reliable maps each showing one of these features (Dawson, 10, and Northern Alberta, 11), are 54°9 [note in original: While stating the latitude of Jarvis Pass to be 54°7′, the map represents it in 54°9′] and 54°2′. In addition to this divergence the blue-print map showed the Sulphur River heading in the same divide as the East Branch of the Moose River, in contradiction of both Wheeler’s map (4) and the map of Northern Alberta, and placed Mt. Kitchi about 30 miles from the Fraser valley, while Donald Phillips stated that it was not less than 40 miles. These and other discrepancies led the writer to believe that the contoured mountain area on the blue-print map was shown in incorrect relation to the Fraser valley, and it was accordingly pushed north to the latitude shown on the map of Northern Alberta. Subsequent correspondence with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway brought to light another blue-print map of the same region which developed to be the original (1). On this the mountain area was shown in its northern location, with Jarvis Pass in 54°9′. The evidence now seemed conclusive that this was the correct interpretation and it was so accepted in the compilation of the map.

With the northern section of the map thus accounted for, the compilation of the remainder was relatively easy. In the southeast Wheeler’s excellent photographic survey of the Mt. Robson region (4) was used and its contours interpreted by hachuring in the style of the Sectional Map of Western Canada (7), while retaining from Wheeler’s map the representation of the glaciers, which are left blank on the Sectional Map. To the southwest the topography was expanded from McEvoy’s contoured map (5). The Fraser River itself was taken from the Pre-emptor’s map (6), while the walls of its trough valley were generalized from the contours in the original edition of the Grand Trunk map (1). The region adjoining the Wheeler survey to the north was filled in from Dr. Collie’s map (3). (This map also includes the Mt. Robson region, but here it is, of course, superseded by Wheeler’s map.) This left a wedge-shaped gap, 5 to 15 miles wide, between Collie’s survey and the Grand Trunk Pacific survey. For this section Donald Phillips’s sketch map (2) was alone available.

Not only here, but throughout the map his data have been used in correction or amplification of the other sources. For instance, on the northwestern edge of Wheeler’s map Wolverene Creek is connected with the head of the Beaver; instead there should be a divide between them, as shown on the present map and also on Collie’s. At Meadow Lake Pass the Grand Trunk Pacific map shows the divide to lie south of the largest lake: Phillips states it to lie north of it. On the Grand Trunk map neither the bend of the Big Salmon around the southern base of Mt. Kitchi is shown nor Providence Creek. The headwaters of the latter are there conjectured to flow into Black Bear Creek over what is actually Providence Pass: the drainage in this region has therefore been altered according to information furnished by Miss Jobe and Donald Phillips.

From what has been said it will be evident that the various sections of the map are of very unequal value, Wheeler’s survey and the Fraser River are the most correct; next in accuracy come the Grand Trunk Pacific survey and McEvoy’s survey, which are of reconnaissance grade; then comes Collie’s survey and, finally, the section based on Phillips alone.

While all the other sections of the map are geometrical reductions of the originals, in the case of Collie’s survey distortion was necessary in order to make it fit. Using the head of the Smoky River and the confluence of the Jack Pine with it as two points whose location was known (one from Wheeler’s map, the other from the Grand Trunk map), the Smoky River was fitted in between these two points. This gives it a more meridional trend than in Collie’s map, where its direction is north-northwest. It also gives it a change in trend at the mouth of the Wolverene which is not present on Collie’s map, where the whole river from Calumet Creek to the edge of the map is rectilinear. Which version is correct remains to be seen. The prevailing northwest-southeast trend of the structural valleys in this part of the Rocky Mountains would seem to argue for the greater correctness of Collie’s map. On the other hand, the trend is incorrect on his map of several valleys in the Mt. Robson region, as indicated by Wheeler’s later and more correct survey; and furthermore a difference is apparent from the map in the structure of the mountains north of the transverse courses of the Jack Pine and Smoky, where transverse and not longitudinal valleys predominate. The influence of this structural change might extend south to the upper Smoky valley. The upper valley of the Jack Pine and, consequently, the whole region between it and the Smoky have also been swung into a more meridional position. The trend of the upper Beaver having been retained, on the basis of Phillips’s sketch map, as on Collie’s map, this has resulted in a widening of the ridge between the upper Beaver and Jack Pine.

In the east the adjustment of Collie’s survey was very satisfactory. By making the bend of the Middle Branch of the Stony River (53°15′ N. and 118°50′ W.) coincide with the same feature on the Wheeler map and drawing the remainder of the Stony drainage in its geometrical proportions, the North Branch of the Stony, taken from the Grand Trunk map, when continued to the southeast, coincided with the Deer Creek of Collie’s map. The interpretation of Deer Creek as the lower North Branch seemed to be confirmed by the Grand Trunk map, on which the main Stony is shown as surveyed from its mouth to the junction of the Middle Branch, with only a small piece left conjectural between it and the North Branch. If this interpretation be correct, then Collie’s North Branch (the next valley to the west, left unnamed on the present map) would simply be another longitudinal valley, presumably also leading over to the Sulphur River.

A different identification from Collie is here also given in the case of the South Branch of the Stony. By this name Collie designates the short transverse valley, here left unnamed, which forms the upper continuation of the lower Middle Branch. On Wheeler’s map the head of the South Branch is shown as here reproduced. As this seems to be a major tributary, Wheeler’s designation has been retained and its conjectural course shown as on the map of Northern Alberta, on which Wheeler’s designation is also followed.

It has been thought wise to enter into the details of the construction of the map, inasmuch as a compilation of this nature, as contrasted with an original survey, is based on critique and not on observation, and a judgment as to its correctness can only be formed when the methods employed are known. In spite of its obvious lack of finality, the map, it is believed, constitutes a more complete representation of the region according to our present state of knowledge than heretofore available. Comparison with the latest editions of the largest-scale general maps including this region — the map of Northern Alberta (11) and the map of British Columbia (12) — will bear this out. Aside from the fact that these maps do not show relief, they have not always utilized all the sources. While reproducing Wheeler’s survey the map of Northern Alberta (corrected to Sept. 1, 1914) does not utilize Collie’s survey, although it was published in March, 1912. Both maps in the representation of the headwaters of the Smoky are evidently based on the Grand Trunk map which has doubtless been filed with the Dominion railway commissioners. While the British Columbia map reproduces it in toto, the Northern Alberta map has modified the region near the confluence of Sheep Creek with the Smoky and the course of the Muskeg River, presumably on the basis of the surveys of the Fifteenth and the Sixteenth Base Lines (8 and 9). While the survey of the base lines themselves is probably satisfactory, the topography on each side does not claim to be [note in original: On map 8 the Smoky crosses the line between townships 58 and 39 in range 7, on map 9 it crosses the same line in the corresponding part of range 6. This has led to its being stretched on the map of Northern Alberta.], and it would seem wiser to retain the railroad survey, which is at least consistent with-in itself. With regard to the upper courses of the Smoky, Jack Pine and main Beaver these two maps are either conjectural or are left blank. But their course determines the continental divide and, consequently, the boundary between Alberta and British Columbia, which follows the divide from the United States boundary to the 120th meridian. The present map is therefore able to offer some additional information on this question of practical interest.

In conclusion it is a pleasure to acknowledge the Society’s indebtedness to the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway for the permission to reproduce its blue-print map and particularly to its Assistant Chief Engineer, Mr. A. A. Woods, for his unfailing courtesy in answering inquiries. Dr. E. Deville, the Surveyor General of Canada, was also good enough to answer several inquiries as to the reliability of various government maps. During compilation, Miss Jobe and Mr. Phillips kindly checked up the map from notes and photographs and offered helpful suggestions.

Any information tending to the correction or expansion of the map will be gratefully received by the Society.

W. L. G. J.

List of maps

1. [Blue-print map by Grand Trunk Pacific Railway]. 1:190,080. In two latitudinal strips cover- ing 56°12° 52°45′ N. and 123°15 – 117° W. 1906. [Original. Correct location of mountain region. Shows geographic coordinates and township squares. Relief in contours. Routes of engineers’ reconnaissance surveys shown (R. W. Jones, D. D. Sprague, A. S. Going), affording criterion as to reliability of various sections. Fraser valley in reconnaissance.]

1a. [Blue-print map by Grand Trunk Pacific Railway]. 1:190,080. Section covering 54°20′- 52°45 N. and 129°15′ – 118°30 W. 1914%. [Copy from above. Incorrect location of mountain region. No geographic coordi- nates or township squares. Fraser valley from land surveys.J

2. [Manuscript sketch map by Mary L. Jobe and Donald Phillips]. 1:200,000 approx. 54°10- 32345 N.; 12290′ -118025 W. 1915.

3. Part of the Rocky Mountains north of the Yellowhead Pass. from a plane table survey by Professor J. Norman Collie, F.R.S., 1910-11. 1:500,000. 53°35 – 52°35 N.: 12000° – 117930 W Accompanies ” Exploration in the Rocky Mountains North of the Yellowhead Pass ‘ by J. Norman Collie, Geogr. Journ., Vol. 39, 1912, No. 3, pp. 223-235. [Relief in shading.]

4. Topographical Map Showing Mount Robson and Mountains of the Continental Divide North Yellowhead Pass. From photographic surveys by Arthur O. Wheeler. [1:100,000]. (53°17’ – 52°45 N.; 119°97 – 118°20 W. Accompanies The Alpine Club of Canada’s Expedition to Jasper Park. Yellowhead Pass and Mount Robson Region, 1911,* by A. O, Wheeler, Canadian Alpine Journ., Vol. 4. 1919, pp. 1-83; also “Special Number” of Canadian Alpine Journ., 1912; also “The Mountains of the Yellowhead Pass by A. 0. Wheeler, Alpine Journ., Vol. 26, 1912, pp. 382-400; also Annual Report Topogr. Surv. Branch for 1911-12, Ottawa, 1918. (Relief in contours.]

5. Map showing Yellowhead Pass Route from Edmonton to Tête-Jaune Cache. 1:506,880. 58°45 – 52-38 N.; 110°34 – 118°18 W. Accompanies Report on the Geology and Natural Resources of the Country Traversed by the Yellowhead Pass Route from Exmonton to Tête Jaune Cache ‘ by James McEvoy, Sub-report D (44 pp., 1900), Annual Report, Geol. Survey of Canada, for 1695, N. S., Vol. 11, 1901. [Relief in contours.]

6. Pre-emptor’s Map [of British Columbia]: Tête Jaune Sheet (No. 8 H. 1:190,080. 53°48′- 52°41 N.; 121°10° -118°22′ W. Dept. of Lands, British Columbia. Revised to April 8, 1914. (No relief.]

7. Sectional Map [of Western Canada]: Yellowhead Sheet. 1:190.080. 53°12′ – 52098′ N.: 120°0′- 118°0′. Topographical Surveys Branch, Dept, of the Interior, Ottawa. Revised to Oct. 10, 1912.

[Relief of Wheeler’s survey in hachuring.]

8. Sketch Map Showing Topography of the Fifteenth Base Line across Ranges 25, 26 and 20, West of 5th Meridian, and Ranges 1 to 8, West of 6th Meridian, Province of Alberta. 1:380,160. (54°4′- 53°43 N.; 119°14 – 117°33′ W.. Accompanies “Extracts from the Report of A. H. Hawkins, D. L.S.’ Appendix No. 21, Annual Report Topogr. Surveys Branch for 1209-1910, pp. 84-91, Ottawa, 1911. [Generalized relief.]

9. Sketch Map of the Sixteenth Base Line across Ranges 5 to 13 and the Seventeenth Base Line across Ranges 9 to 14, West of the 6th Meridian. 1:380,160. [54°-45′ – 54°4” N.; 120°7- 118°36]. Accompanies, in pocket of report for 1911-12, “Abstract of the Report of George McMillan, D.L S.”, Appendix No. 35, Annual Report Topogr. Surveys Branch for 1910-1911, pp. 116-118, Ottawa, 1912. [No relief.]

10. Map of Part of British Columbia and the Northwest Territory from the Pacific Ocean to Fort Edmonton. Sheet II. 1:506.880. 57°8′ – 53°49 N.: 124°35 – 117°55 W. Accompanies “Report of an Exploration from Port Simpson on the Pacific Coast to Edmonton on the Saskatchewan, Embracing a Portion of the Northern Part of British Columbia and the Peace River Country, 1879, by George M. Dawson, Sub-report B (165 pp., 1881), Report of Progress, Geol. Surrey of Canada, for 1579-50, Montreal, 1851.

11. Northern Alberta: Map Showing Disposition of Lands, Prepared under the direction of F. C. C. Lynch, Superintendent of Railway Lands, [by] J. E. Chalifour, Chief Geographer, 1:792,000. 60°15′ – 52°50° N.; 120°20 – 109°15 W. Dept. of the Interior, Ottawa. Eighth edition, corrected to Sept. 1, 1914.

12. British Columbia. [Compiled under the direction of] G. G. Aiken, Chief Geographer. 1:1,125,000. 61° -48° N.; 140° – 112½° W. British Columbia Dept. of Lands, Victoria, B. C., 1912.