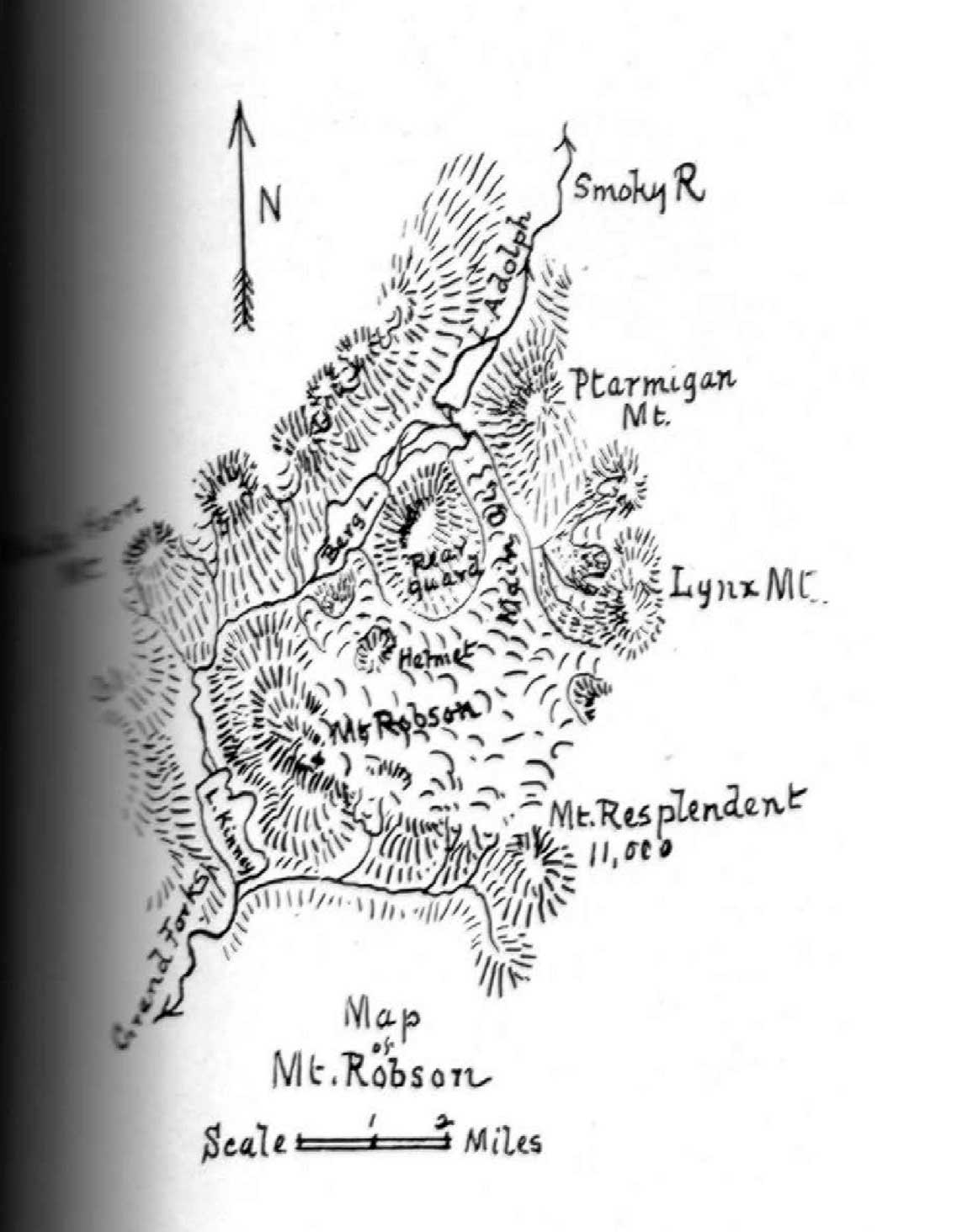

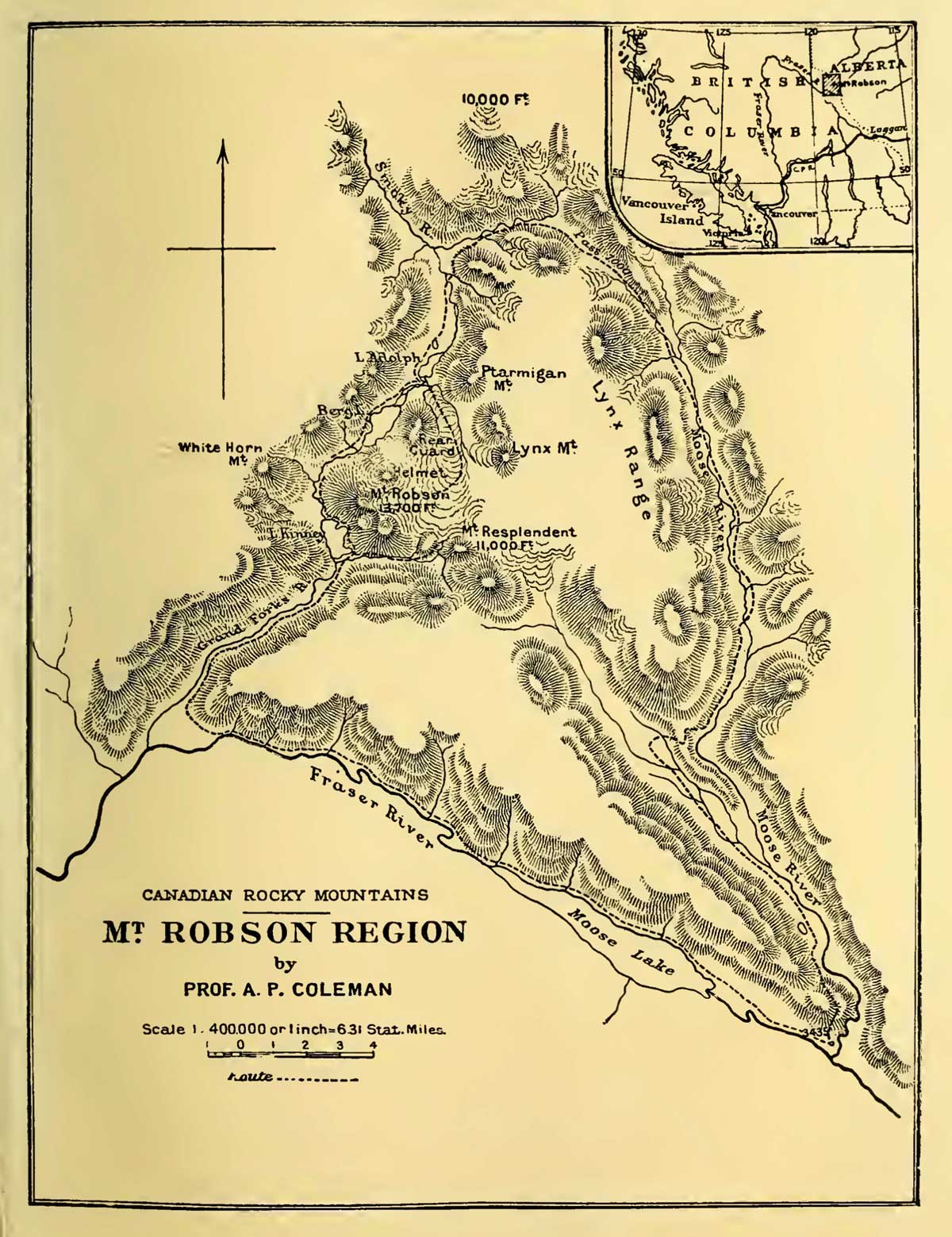

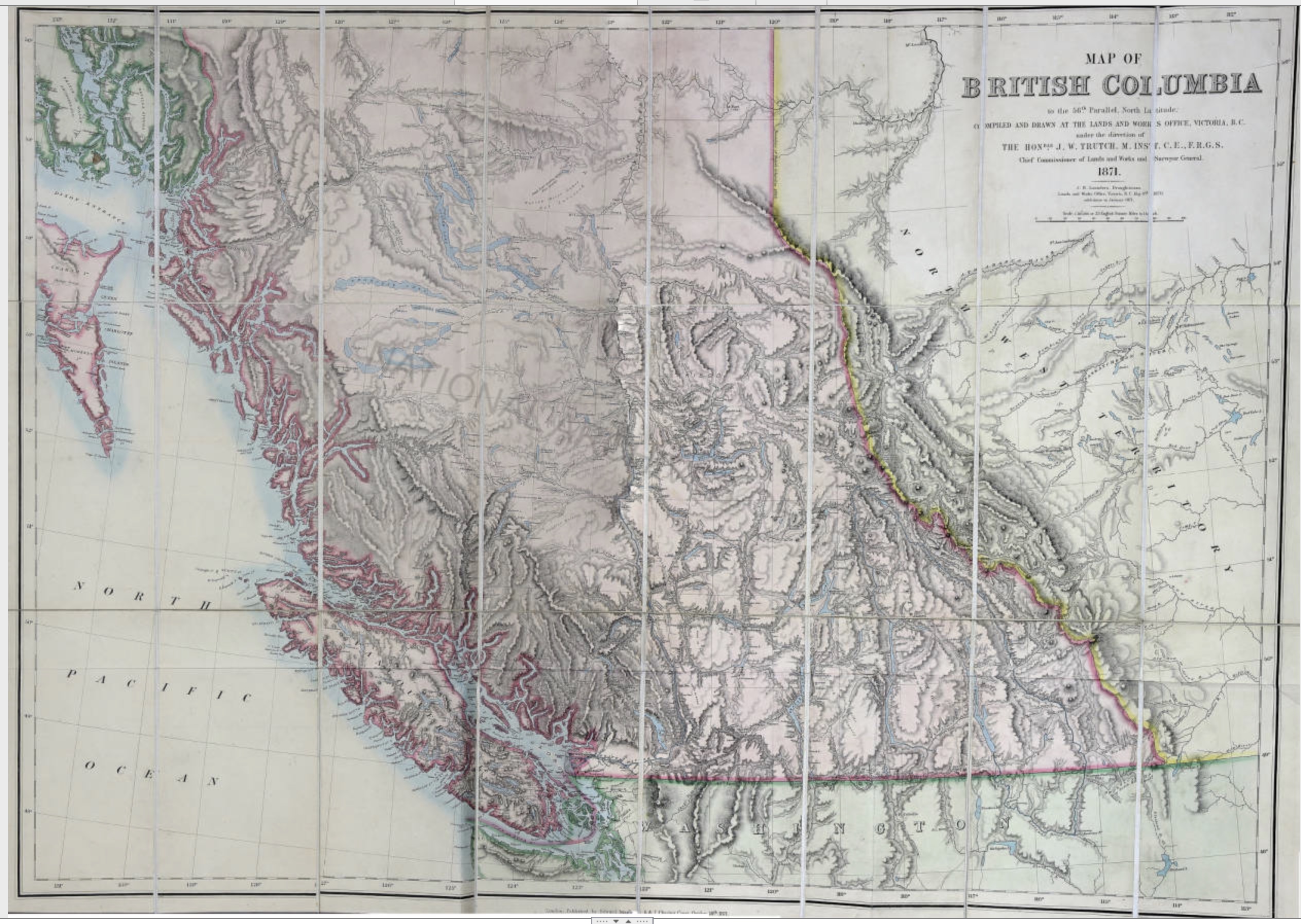

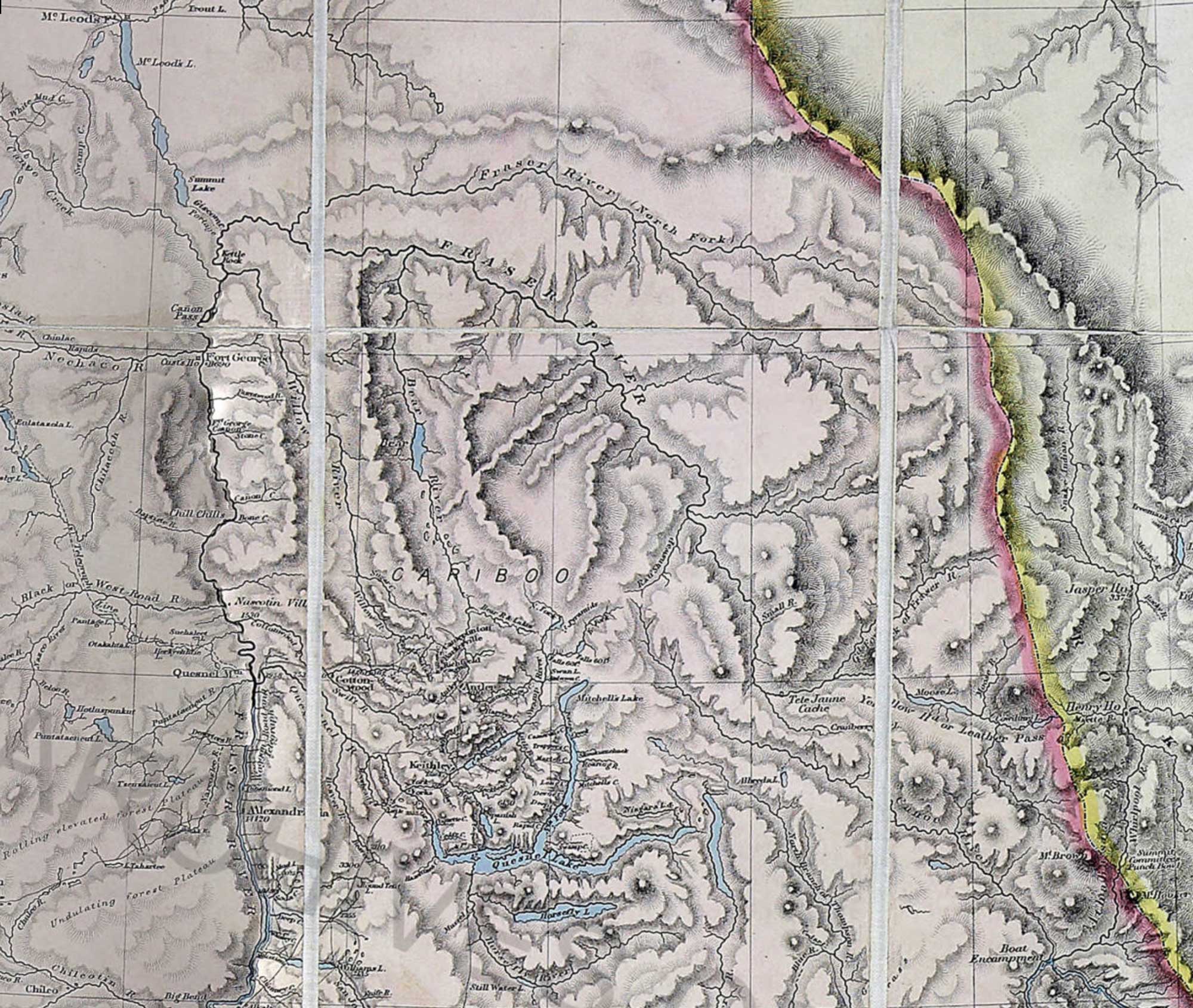

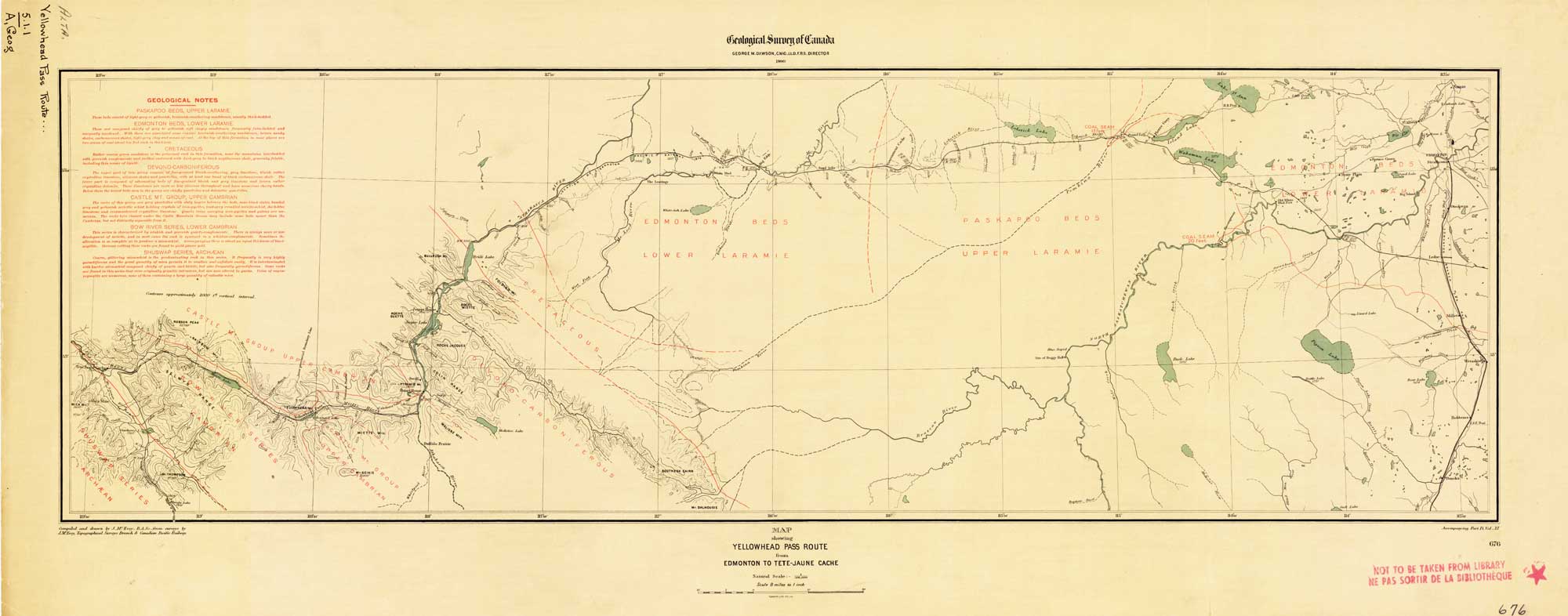

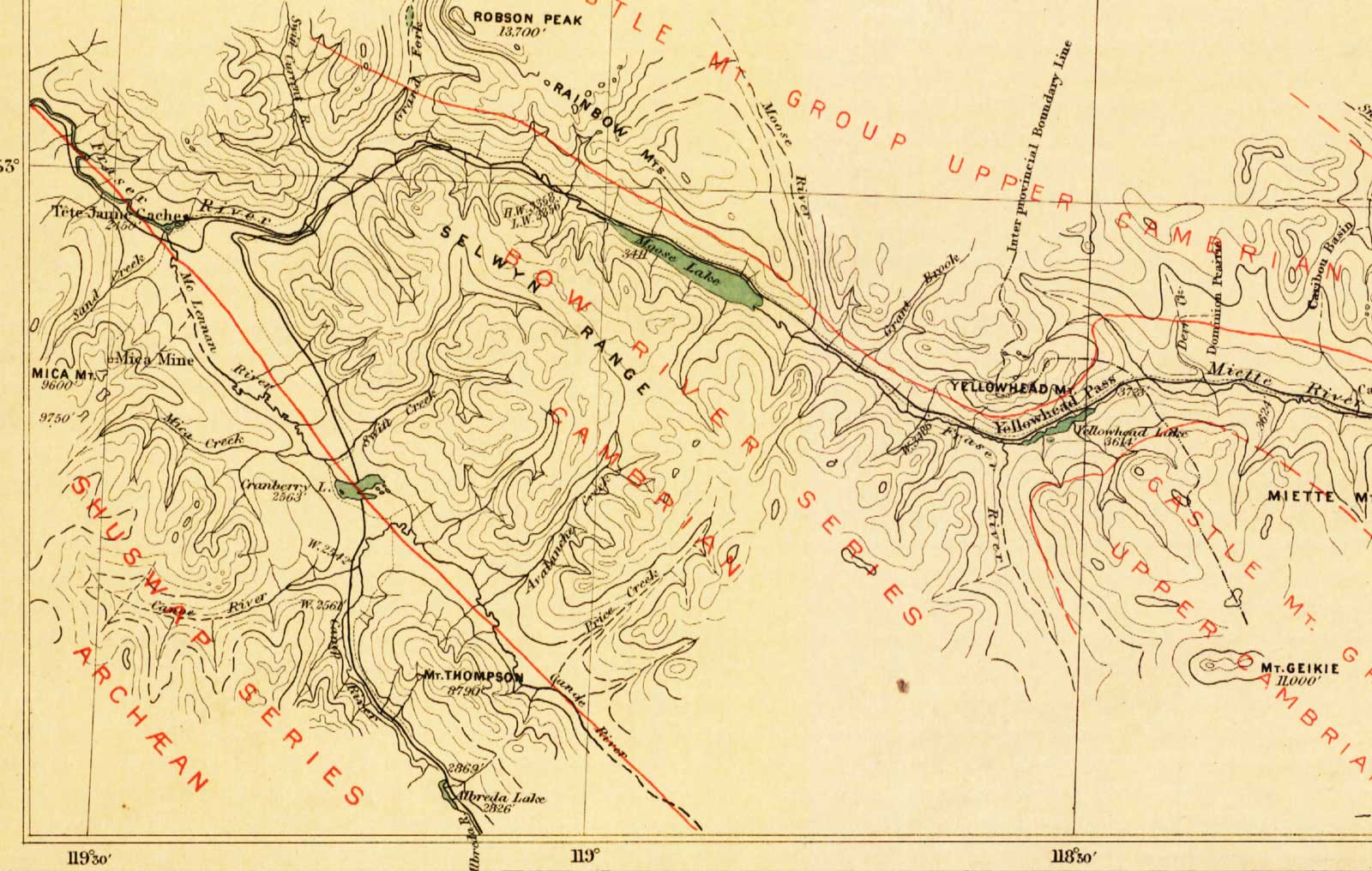

Map Showing Yellowhead Pass Route From Edmonton To Tête-Jaune Cache. James McEvoy, 1900.

Natural Resources Canada

Map Showing Yellowhead Pass Route From Edmonton To Tête-Jaune Cache.

James McEvoy, 1900. (Detail of Yellowhead Pass to Tête Jaune Cache)

Natural Resources Canada

In 1898 McEvoy surveyed the Athabasca River valley for about 240 kilometres east of the Yellowhead Pass, and down the Fraser River on the west side of the pass for another 120 kilometres.

The splendid report of James McEvoy, published by the Geological Survey of Canada in 1900, dealing with the geology and natural history resources of the country traversed by the Yellowhead Pass route from Edmonton to Tête-Jaune Cache, contains the most comprehensive and reliable geographical information that has yet been published, and also contains the only geographical map published of that route on a sufficiently large scale to be of value.

— Arthur Oliver Wheeler [1860–1945], 1912

Albreda Lake

Albreda River

Athabasca River

Avalanche Creek

Brûlé Lake

Buffalo Prairie

Caledonian Valley [as “Caledonia Valley”]

Colin Range

Cranberry Lake

Dominion Prairie

Mount Geikie

Grand Fork

Grant Brook

Jasper Lake

McLennan River

Mica Mountain

Mica Creek

Miette Hill [as “Miette Mts.”]

Miette River

Moose Lake

Moose River

Price Creek

Rainbow Range

Mount Robson [as “Robson Peak 13,700’”]

Roche Suette

Roche Miette

Sand Creek

Selwyn Range

Snaring River

Stoney River [as “Stony River”]

Swift Creek

Swiftcurrent Creek

Tête Jaune Cache

Whirlpool River

Yellowhead Lake

Yellowhead Pass

- McEvoy, James [1862–1935]. Report on the geology and natural resources of the country traversed by the Yellowhead Pass route from Edmonton to Tête Jaune Cache comprising portions of Alberta and British Columbia. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada, 1900. Natural Resources Canada

- McEvoy, James [1862–1935]. “Map Showing Yellowhead Pass Route From Edmonton To Tête-Jaune Cache.” (1900). Natural Resources Canada

- Wheeler, Arthur Oliver [1860–1945]. “The Alpine Club of Canada’s expedition to Jasper Park, Yellowhead Pass and Mount Robson region, 1911.” Canadian Alpine Journal, Vol. 4 (1912):9-80